Hoe kan iemand schuldig zijn aan iets wat hij niet heeft gedaan (in het bijzonder als er helemaal geen verband mogelijk is)?

How can someone be guilty of something they didn’t do (especially when there is no possible connection)?

Fairness is what justice really is versus

Fairness by the time justice is done

“…, it is still a beautiful world.”

(cfr. The second link at the top leads to an inspiring part of the website.)

When the Truth Comes Out, The Rest Will Follow

History has shown that institutions often resist accountability until the weight of undeniable truth forces change.

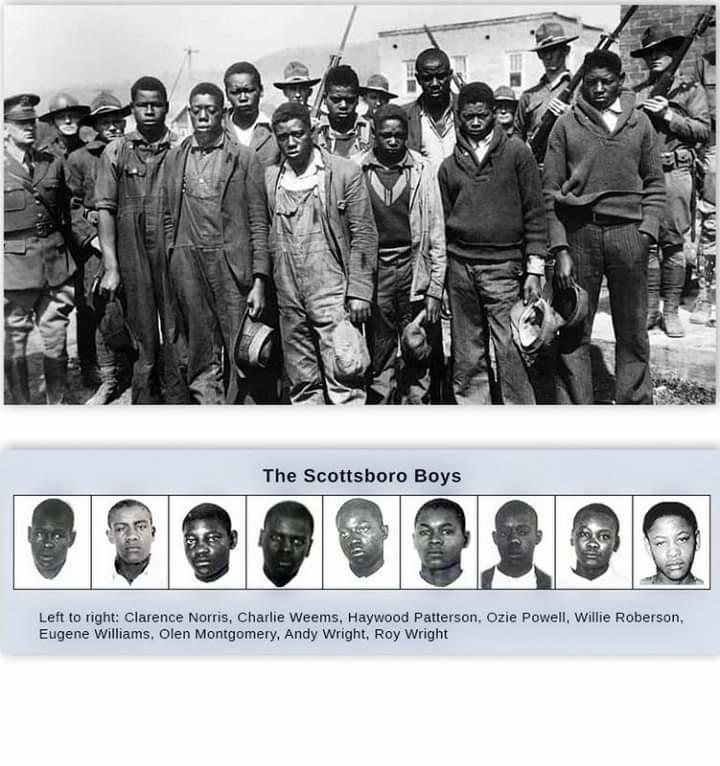

The wrongful convictions of the Scottsboro Boys, the Central Park Five, and victims like Walter McMillian reveal how deeply flawed justice systems can be.

The Outreau Affair (France) is a tragic example, where false accusations and concealed evidence led to 13 wrongful convictions and 5 years of unjust imprisonment in the early 2000s.

The British Post Office scandal stands as a stark example—where those in power ignored the truth for years, until relentless campaigning forced it into the open.

The website views justice from the perspective of people who are incompatible with the object of justice and, for an inexplicable reason, are pulled into the justice system. A inconceivable justice paradox, then. Something that should never happen.

This page explores these cases as a Litmus Test for justice: When systems fail, who pays the price? And once the truth emerges, does justice truly follow?

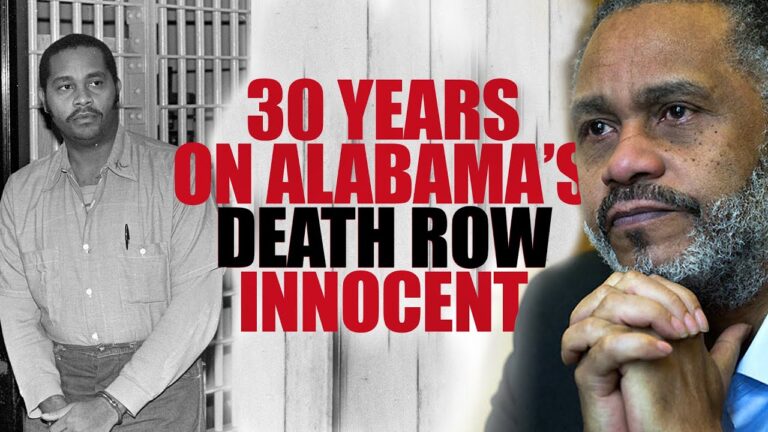

Tommy Lee Walker: A 70-Year Fight for Justice

The stories that follow give voice to those who were failed by justice — and challenge us to face what that failure reveals.

Wanneer de Waarheid Naar Buiten Komt, Volgt de Rest

De geschiedenis laat zien dat instituties zich vaak pas verantwoorden wanneer de onmiskenbare waarheid hen daartoe dwingt.

De onterechte veroordelingen van de Scottsboro Boys, de Central Park Five en slachtoffers zoals Walter McMillian tonen aan hoe diep de gebreken in rechtssystemen kunnen gaan.

De Outreau Affaire (Frankrijk) is een ander tragisch voorbeeld, waarbij valse beschuldigingen en verborgen bewijsmateriaal leidden tot 13 onterechte veroordelingen en 5 jaar onterechte gevangenisstraf in het begin van de jaren 2000.

Het Britse Post Office-schandaal is een ander schrijnend voorbeeld – waar de waarheid jarenlang werd genegeerd, totdat onvermoeibare inspanningen haar uiteindelijk aan het licht brachten.

Deze website bekijkt justitie vanuit het perspectief van mensen die onverenigbaar zijn met het voorwerp van justitie en, om een onverklaarbare reden, voor het gerecht gesleept worden. Een onvoorstelbare justitieparadox dus. Iets dat nooit zou mogen gebeuren.

Deze pagina onderzoekt deze zaken als een Lakmoesproef voor Gerechtigheid: Wanneer systemen falen, wie draagt dan de gevolgen? En als de waarheid eenmaal bekend is, volgt gerechtigheid dan echt?

Tommy Lee Walker: A 70-Year Fight for Justice

De verhalen die volgen geven een stem aan wie door justitie in de steek werden gelaten — en dagen ons uit om onder ogen te zien wat dat falen onthult.

When justice fails, who speaks for the innocent?

Some were only children. Some lost decades. All were betrayed.🌿

👉 Justice – A Completely Different World

This page is not just about names. It’s about what kind of society we become when we look away.🌿

👉 When Silence Becomes Complicity

This page looks beyond individual cases — and exposes the deeper pattern: when truth becomes inconvenient, and silence becomes a strategy.🌿

👉 Challenging Justice: The British Post Office Scandal

What if justice doesn’t protect the innocent — but protects itself?

🌿

👉 Justice – Your life hangs by a thread – Conscience Ignored

A single thread holds a life — until justice forgets what it’s for.

🌿

👉 The Soul Left Unseen: What Justice Forgot

When the soul is forgotten, justice becomes hollow — and humanity fades into silence.

🌿

👉 Justice, the Soul, and Conscience

This page is not only about justice — it’s about soul, memory, and the cost of silence.

🌿

Before justice, before conscience — there is the soul that gives them meaning.

🌿

When lives are on the line, silence and neglect are not neutral — they are a choice.

🌿

When institutions turn away, the damage isn’t accidental — it’s sustained by design.

🌿

👉 So Far from the Truth: Beyond Absurdity, Inhuman Cruelty

When innocence is sacrificed for false certainty, the damage is not just unjust — it’s inhuman.

🌿

👉 The Truth Will Eventually Come Out

When deception is rooted in power, truth’s inevitable emergence is a victory for integrity and justice.

🌿

A deep dive into how ingrained systems of power perpetuate inequality, where justice is often a privilege, not a right.

🌿

👉 When the Rule of Law Fails

A look at how the justice system’s flaws allow injustice to thrive, where the powerful are shielded and the innocent suffer, often with life-altering consequences.🌿

👉 Unveiling What Really Happened

A closer look at the justice system’s failure to protect the innocent — where truth is buried, and injustice thrives.🌿

👉 The Pot Calls the Kettle Black

When those in power point fingers, it’s worth asking: who are they hiding from?Explore how hypocrisy shapes the systems we trust and what happens when justice is served with a double standard.

🌿

👉 Pit Somebody Against Somebody

What happens when people are pitted against each other — when the system turns conflict into a spectacle?Discover how division and manipulation fuel a cycle of injustice, and the devastating human cost of playing people against one another.

🌿

👉 The Cost of Inaction: When Knowledge Becomes Complicity

Explore the tragic consequences of knowing the truth yet choosing silence — a story where inaction became the greatest betrayal.🌿

👉 Justice Gone Wrong: Out of the Frying Pan Into the Fire

When justice fails, the consequences aren’t just unfair—they’re catastrophic. This page explores the human cost of legal systems that go astray, where escaping one nightmare only leads to another.🌿

👉 Money Makes the World Goes Round

A reflection on how money shapes power, decisions, and human lives in ways that often go unnoticed — or worse, unchallenged.

🌿

👉 The Bottom Line

When the systems we trust fail, it’s not just a failure of law — it’s a failure of humanity.🌿

👉 There Is No Such Thing as Honesty

What happens when truth is bent, avoided, or left unsaid? Explore the reality of honesty in a world where people often fail to be straightforward, even in the simplest moments.🌿

👉 Behind the Façade of Society: The Dark Side of Injustice

What happens when the truth is hidden behind the illusion of order and fairness? Explore the hidden systems of power that perpetuate injustice, and the human lives that pay the price.

🌿

👉 Walking on Eggshells — When Speaking Truth Becomes Dangerous

When honesty endangers lives — the lonely battle of those who refuse to stay silent.🌿

👉 The Salt Path Heist: Exposing the Con and the Corruption

A deep dive into the shocking lies and betrayal behind a massive scandal that shattered trust and revealed deep corruption.🌿

👉 Questioning Society – A Moral Imperative in Ethics and Law

This page delves into the ethical and moral responsibilities we face in challenging societal norms and legal systems that often fail to protect what is just. A call to reflect on the law’s role in shaping a fair society.

🌿

👉 Jeffrey Epstein: The Secrets Behind the Story

When power and mystery collide, the truth hides in plain sight — but it’s only a matter of time before it unravels.🌿

👉 The Power of Cross-Examination: How Tactics Can Undermine Justice

A closer look at how aggressive legal tactics, like cross-examination, can manipulate the truth, especially when the accused is vulnerable. The balance between justice and strategy is often blurred.🌿

👉 Lord Peter Mandelson: Power, Corruption, and Controversy

An exploration of the controversial career of Lord Peter Mandelson, from his rise to power to his connections with scandal, corruption, and his ties to controversial figures.

🌿

👉 Organized and Systemic Failure: Lies Behind Andrew’s Photo

A deep dive into the Epstein scandal, uncovering the lies and systemic failures that allowed powerful figures to evade accountability, focusing on the truth behind the infamous photo of Prince Andrew with Virginia Giuffre.

🌿

👉 The Royal Scandal – When Power Meets Injustice

A powerful figure’s fall, a story of scandal that exposes the flaws within institutions meant to protect us.🌿

👉 The Real Andrew Mountbatten-Windsor: In Hindsight

This page offers a reflective exploration of Andrew Mountbatten-Windsor, delving into his public image, actions, and character. Through a deeper look at his life and the controversies surrounding him, it invites readers to reconsider what hindsight reveals about the man behind the headline🌿

Contents

In The News

1 Introduction

The Essential Question in simple words is:

how can someone be guilty of something they didn’t do?

Alea iacta est

👉 The Naked Truth of a Broken Society

This page peels back the layers of a fractured system, revealing the truths we often ignore and the consequences of a society that fails to protect its most vulnerable.

And yet, what happens when those in power are…

It is already the subtitle of the website.

John Bunn was only 14

It is disturbing and incomprehensible.

Cut to the chase:

When you reflect on the event by clicking the link above and knowing the facts, it becomes impossible to understand how such things could have happened.

“A Web of Injustice”

- This collection explores over 150 stories of systemic failures, wrongful convictions, and institutional negligence across the globe. From the UK’s Post Office Scandal to the Rodney King case in the U.S., these cases highlight deep-rooted injustices, where flawed legal systems, abuse of power, and sheer human error resulted in innocent lives being shattered.

- Each case represents a piece of a larger puzzle—one that questions the integrity of justice, the failures of those in power, and the resilience of those who fight for the truth.

- Explore the links for a closer look at the causes, consequences, and ongoing efforts to correct these monumental wrongs.

- It’s about the countless individuals whose lives, like a thunderclap on a clear day, are suddenly changed forever.

Kom ter zake

Wanneer je de bovenstaande link volgt, de feiten kent en over de gebeurtenis nadenkt, wordt het duidelijk hoe onbegrijpelijk het is dat zoiets heeft kunnen gebeuren.

“Een Web van Onrecht”

- Deze verzameling onderzoekt meer dan 150 verhalen van systematische mislukkingen, onterechte veroordelingen en institutionele nalatigheid wereldwijd. Van het Post Office-schandaal in het VK tot de zaak Rodney King in de VS, deze gevallen benadrukken diepgewortelde onrechtvaardigheden, waarbij gebrekkige rechtsystemen, machtsmisbruik en pure menselijke fouten leidden tot verwoeste onschuldige levens.

- Elk geval vertegenwoordigt een stuk van een groter geheel – een geheel dat de integriteit van het rechtssysteem in twijfel trekt, de mislukkingen van de machthebbers blootlegt en de veerkracht van degenen die voor de waarheid strijden toont.

- Verken de links voor een nadere kijk op de oorzaken, gevolgen en voortdurende pogingen om deze monumentale fouten te herstellen.

- Het gaat om de ontelbare individuen wiens leven, als een donderslag bij heldere hemel, plotseling voor altijd verandert.

Let’s come straight to the point:

- deliberate wrongdoing within entities in the justice system, It Mirrors Madness,

- elaborated in points A to P ranging from The Inconceivable to The Aura of Perfection.

- This includes a comprehensive 16-point overview that provides a glimpse into the essence of the website.

- One compelling example is highlighted by Lord Justice Fraser in point N where he emphasizes

A Cock-and-Bull Story with the strongest language:- ‘This approach by the Post Office has amounted, in reality, to baseless assertions and denials that ignore what has actually occurred.

- It amounts to the 21st-century equivalent of maintaining that the Earth is flat’

- However, as the saying goes: “A lie can travel halfway around the world while the truth is putting on its shoes.”

- Even if it takes endless years, it was the stubbornness of one man that changed everything.” Click here for more.

Laten we ter zake komen:

- opzettelijk wangedrag binnen entiteiten in het rechtssysteem, het weerspiegelt waanzin,

- uitgewerkt in de punten A tot en met P, variërend van ‘Het Ondenkbare’ tot ‘De Aura van Volmaaktheid’.

- Dit omvat een uitgebreid 16-puntenoverzicht dat een beeld biedt van de essentie van de website.

- Een treffend voorbeeld wordt benadrukt door Lord Justice Fraser in punt N, waar hij met de krachtigste bewoordingen spreekt over ‘Een Kletskoekverhaal’:

- ‘De benadering van de Post Office komt in werkelijkheid neer op ongefundeerde beweringen en ontkenningen die negeren wat er daadwerkelijk is gebeurd.

- Het is het 21e-eeuwse equivalent van volhouden dat de aarde plat is.’

- Echter, zoals gezegd: “Al is de leugen nog zo snel, de waarheid achterhaalt ze wel”.

- Al heeft het eindeloos veel jaren gevergd, het was de koppigheid van één man die alles veranderde.” Klik hier voor meer.

“Your very existence as a human is under threat.”

If you think it can’t happen to you,

watch these 7 innocent people prove otherwise.

They had values. They were innocent.

The system broke them.

The Ethical Mirror

The Wake-Up Call

- With no hope of escape, being trapped in prison against all odds?

- Can one truly grasp the existential crisis this causes for the individual involved?

- Life is thus destroyed by deliberate, deceptive systems within the entire apparatus.

- The justice system is at stake, not the individuals involved.

- Under impossible circumstances, a visibly intrinsically false file was created.

- The deception is appalling, and it is incomprehensible that it was not stopped.

- And last but not least, in a very broad context, it is well known that what is being brought against the person involved is nothing more than a farce – completely incompatible with the person – and certainly not the truth.

- The Dark Arts of the Justice

- Zonder uitzicht op een onmogelijke wijze in de gevangenis terechtkomen?

- Kan men beseffen welk existentieel probleem dat teweegbrengt bij de betrokken persoon?

- Het leven wordt dus kapotgemaakt door bewuste, bedrieglijke systemen binnen het totale apparaat.

- Het justitiesysteem staat dus ter discussie, niet de betrokkenen.

- Onder onmogelijke omstandigheden is er een zichtbaar intrinsiek vals dossier opgesteld.

- Het bedrog is weerzinwekkend, en het is niet te begrijpen dat het niet gestopt is.

- En last but not least, in een heel ruime context is geweten dat wat de betrokken persoon wordt ten laste gelegd, niet meer is dan een klucht – onverenigbaar met de persoon – en dus zeker niet de waarheid.

- The Dark Arts of the Justice

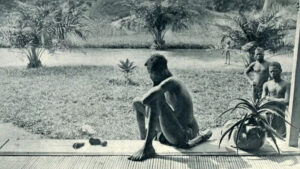

2 We Are in a Dog Fight

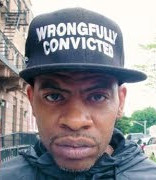

John Bunn was in a dog fight for justice,

battling for 27 years against a wrongful conviction

until he was fully exonerated in 2018.

The injustice he suffered left an indelible mark on him.

Even after 27 years,

the pain still lingers,

leaving a profound mark on his soul.

On August 13, 1991, at 4 in the morning,

I was at home sleeping when, at that time,

two police officers were shot, and the car was stolen.

Bunn was fully exonerated in 2018,

27 years after being wrongfully convicted.

It is beyond understanding that an innocent 14-year-old child could be deceitfully burdened with something entirely incompatible with him, causing immense suffering.

John Bunn stands as a central theme on the website, exposing both the incomprehensible nature of what happened to him and the undeniable failure of justice.

The contact with an intrinsically bad person – namely detective Louis Scarcella – is the core issue. This has nothing to do with justice.

John Bunn stands before the judge 27 years after his conviction, in tears, overwhelmed by the intense grief and pain he has had to endure as a result of sheer deceit.

Het is onbegrijpelijk dat een onschuldig kind van 14 jaar op bedrieglijke wijze wordt opgezadeld met iets dat volledig onverenigbaar is met hem, en dat hem immens leed berokkent.

John Bunn vormt een centraal thema op de website. Zijn verhaal maakt zowel de onbegrijpelijke gebeurtenissen als het onomstotelijke falen van justitie zichtbaar.

Het contact met een intrinsiek slecht mens – namelijk rechercheur Louis Scarcella – vormt de kern. Dit heeft niets met justitie te maken.

John Bunn staat 27 jaar na zijn veroordeling wenend voor de rechter, overmand door het intense verdriet en de pijn die hij als gevolg van puur bedrog heeft moeten dragen.

3 A Fraud Circuit Is Part of the Justice System!

Liam Allan says: ‘You don’t belong there.’ Andrew Malkinson was arrested with no connection, evidence, or anything else linking him to the crime. Raphael Rowe and an endless list of others endure the cruelty of those who hold power and abuse it. John Bunn’s life was stolen from him.

There are no words to describe what happened to him.

The word ‘exception’ cannot and must not be used.

From the perspective of those it happens to, it must be said that it is a deceptive system.

Een fraude circuit maakt deel uit van het justitiële systeem!

Liam Allan zegt: ‘You don’t belong there.’ Andrew Malkinson werd gearresteerd zonder enige band, aanwijzing of wat dan ook met het misdrijf. Raphael Rowe en een eindeloze lijst van anderen ondergaan de wreedheid van degenen die de macht in handen hebben en deze misbruiken. John Bunn’s leven werd hem afgenomen.

Er zijn geen woorden die kunnen uitdrukken wat hem overkwam.

Het woord ‘uitzondering’ kan en mag niet gebruikt worden.

Vanuit het perspectief van degenen aan wie dit overkomt, moet men zeggen dat het een bedrieglijk systeem is.

A. Inconceivable

What you see in the video is extreme:

young, innocent children,

for example, 14 years old,

being framed in jail,

knowing that there is nothing wrong.

Please click the link

It is incomprehensible that someone

could knowingly do something like this

to someone else’s life.

It is ‘one of the biggest questions of justice’.

Are you still a human being?

Is this still a society?

Think of the opposite of what the 22-year-old Mamoudou did in 30 seconds

for a 4-year-old child.

In other words:

the devil that nails down

14-year-old John Bunn

where he doesn’t belong,

contrasts sharply with the heroism of

a 22-year-old who acts immediately.

This embodies ‘The law of Nature’.

There are moments when injustice is so profound that it defies belief.

John Bunn is exemplary for how the ‘power institution of justice’ is structured and how the corrupt former New York City detective Louis Scarcella effortlessly managed to destroy the life of a 14-year-old child. He is a conman, much like several others that appear on this website.

When justice fails on an epic scale, can you as a human being be indifferent?”

When you find yourself in such a situation, a derailing justice system, and to make matters worse, when justice does not apply to you and yet you are wrongly convicted, and even wrongly imprisoned, you are still bound to a blinded, derailed, and disrupted justice system.

Legal systems are both a solution and a problem. Unconstrained power can cause great injustice.

This is not just John Bunn’s story. It is the story of countless others. And it raises the unthinkable question: If innocence is no defense, who is truly safe?

It is a pattern that repeats itself. Time and again, justice does not fail by accident—it is derailed by those who abuse it. What does it say about a society when innocence is no shield against prosecution? When truth holds no weight in the face of authority?

It’s almost impossible to be exonerated, as evidenced by the examples on this webpage and throughout the website, such as ‘The Putten Murder Case’ in the Netherlands.

Er zijn momenten waarop onrecht zo diepgaand is dat het elke vorm van begrip tart.

John Bunn is exemplarisch voor hoe het ‘machtsinstituut justitie’ in elkaar zit en hoe de corrupte voormalige New York City detective Louis Scarcella, moeiteloos in staat was het leven van een 14-jarig kind kapot te maken. Hij is een oplichter, zoals er meerdere voorkomen op deze website.

Wanneer justitie op epische schaal faalt, kun je als mens onverschillig zijn?

Wanneer je in zo’n situatie terecht komt, een ontspoort justitie systeem, en tot overmaat van ramp, wanneer justitie niet op je van toepassing is en des ondanks je onterecht veroordeelt wordt, en zelfs onterecht in de gevangenis komt, dan nog zit je vastgekluisterd aan een verblind, ontspoort en ontwricht justitie systeem.

Rechtssystemen zijn zowel een oplossing als een probleem. Ongebreidelde macht kan groot onrecht veroorzaken.

Dit is niet alleen het verhaal van John Bunn. Het is het verhaal van ontelbare anderen. En het roept de ondenkbare vraag op: Als onschuld geen verdediging is, wie is er dan écht veilig?

Dit patroon herhaalt zich keer op keer. Justitie faalt niet toevallig – het ontspoort door degenen die het misbruiken. Wat zegt dit over een samenleving waarin onschuld geen bescherming biedt tegen vervolging? Waarin waarheid geen gewicht heeft tegenover macht?

Het is quasi onmogelijk om geëxondereerd te worden, zoals blijkt uit de voorbeelden op deze webpagina en doorheen de website cfr. ‘De Puttense Moordzaak’ in Nederland.

JUSTICE COURSE PREVIEW

Please listen to video 5:

Post office inquiry: Fujitsu manager called bankrupted subpostmaster ‘nasty chap’

B. The essence

You can’t look away from the egregious injustice

faced by these individuals.

Indifference is not an option

when faced with such a significant and severe situation.

It is difficult. It is ‘a sign on the wall’. A Red Flag.

——–

We are dealing with a semblance of reality.

Something that appears to be real or true but is actually deceptive or not entirely genuine.

——–

For example the high-profile case of Lian Allan in Great Britain in 2016 (point 1 below)

‘puts the finger on the sore spot’,

as prosecutor Jerry Hayes himself said, “It is just sheer incompetence”.

——–

The handling of the case was Neither Fish Nor Fowl;

it didn’t meet the standards of justice,

almost as if it was a last-minute decision,

even drawing attention in the House of Commons.

——–

An appearance of reality, jaded, bewildering and surreal.

——–

A semblance, an appearance of reality,

in Dutch ‘een schijnwerkelijkheid’.

——–

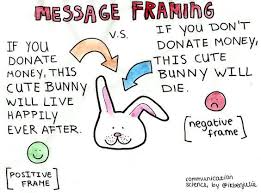

Framing is A Double-Edged Sword, determined by the lens through which one views it. In other words, framing is a complex concept influenced by people’s perspectives.

Framing

Framing is when you subtly steer people toward a certain interpretation by highlighting specific aspects of a subject. It involves selectively presenting information, emphasizing particular elements of a topic or person to create a specific impression, whether in speech or in writing.

In other words Cherry-picking: a tactic where pieces of evidence, statements, facts, or similar situations are selectively mentioned to defend a particular standpoint.

Framing

Met framing, het benadrukken van bepaalde aspecten van een onderwerp, wordt mensen ongemerkt een bepaalde interpretatie opgedrongen. Daarbij selectieve informatie: bepaalde aspecten van een onderwerp of persoon worden benadrukt, waarmee een spreker of schrijver een bepaald beeld creëert.

M.a.w. Cherrypicking; een tactiek waarbij bewijzen, uitspraken, feiten of vergelijkbare situaties selectief genoemd worden om een bepaald standpunt te verdedigen.

When there is framing or cherry-picking, someone playing the role of The Devils Advocate is a good idea.

Cherry-picking

- Notice the wrongful prosecution against Liam Allan, the 19-year-old criminology student in Great Britain in 2016, is based on cherry-picking of a ridiculous false accusation. (Liam Allan is the subtitle and template of the website.)

- Although the police couldn’t ignore the irrefutable evidence, stemming from the complete download of messages from a former girlfriend 7 months prior, which they possessed.

- In other words, this is a serious systemic flaw within the judicial system.

- In September 2015, Liam Allan started university. Reading for a Criminology and Criminal Psychology degree, he was just like any other fresher. But just a few months into his course, he was accused of rape.

- It became a high profile case. Articles in The Times, the BBC and even a question in the House of Commons to Prime Minister Theresa May. Cfr. The Making of.

Cherry-picking

- Bemerk de oneigenlijke vervolging tegen Liam Allan, de 19-jarige criminologiestudent in Groot-Brittannië in 2016, berust op cherry-picking van een idiote valse beschuldiging. (Liam Allan is de subtitel en de template van de website.)

- Hoewel de politie niet om het onweerlegbare bewijs heen kon, afkomstig uit de volledige download van berichten van een vroegere vriendin 7 maanden daarvoor, waarover ze beschikten.

- Met andere woorden, dit is een ernstige systeemfout binnen het justitiële systeem.

- In september 2015 begon Liam Allan aan de universiteit. Hij studeerde criminologie en criminele psychologie en was net als elke andere nieuweling. Maar al na een paar maanden werd hij beschuldigd van verkrachting.

- Het werd een high profile case. Artikels in de Times, de BBC en zelfs een vraag in The House of Commons aan Prime Minister Theresa May. Cfr. The Making of.

‘It wasn’t against my will or anything’: How a rape case built over two years fell apart with a single text.

The basis for Liam’s prosecution relied on paper-thin evidence, which, as Jerry Hayes put it, came dangerously close to resulting in a wrongful conviction. The justice system seemed almost like Candid Camera. Justice, Like a Two-Edged Sword, highlighted the precariousness of the situation. It’s just sheer incompetence. This illustrates the gravity and fragility of our justice system in specific cases.

On a lighter note, have you seen the hilarious ‘Exploding iPhone Prank’ from Candid Camera?

Suddenly Trapped — Without Warning

One moment you’re living your normal life — the next, you’re accused, arrested, and facing prison for something you didn’t do. No warning, no reason, just the machinery of the justice system turning against you.

Like a hidden-camera prank gone horribly wrong, it begins with disbelief — but this time, no one shouts “gotcha.”

This is not comedy. It’s the terrifying reality for people like Liam Allan — pulled into a nightmare by a false accusation, with exonerating evidence ignored or hidden.

When justice misfires, it doesn’t tap you on the shoulder. It hits like a trapdoor opening beneath your feet.

Plotseling en Volledig Vastgelopen

Het ene moment leidt je een normaal leven — het volgende ben je beschuldigd, gearresteerd en dreig je in de gevangenis te belanden voor iets wat je niet hebt gedaan. Geen waarschuwing, geen aanleiding — alleen het systeem dat zich ineens tegen je keert.

Alsof je in een verborgen cameragrap belandt die compleet uit de hand loopt. Alleen roept er nu niemand “gefopt”.

Dit is geen komedie. Het is de angstaanjagende realiteit voor mensen zoals Liam Allan — meegesleurd in een nachtmerrie door een valse beschuldiging, terwijl ontlastend bewijs wordt genegeerd of achtergehouden.

Wanneer justitie ontspoort, krijg je geen teken. Het voelt alsof de grond plotseling onder je voeten verdwijnt.

The situation echoed the eerie authenticity of a Candid Camera episode, where individuals, unsuspecting and enveloped in the smoke of a false reality, believed in the impending explosion, much like how baseless allegations almost ensnared Liam Allan in a wrongful conviction, showcasing the fragile trust within our justice system.

De situatie weerspiegelde het griezelige realisme van een aflevering van Candid Camera, waar individuen, onwetend en omhuld door de rook van een valse realiteit, geloofden in de dreigende explosie, net zoals ongegronde beschuldigingen bijna Liam Allan in een onterechte veroordeling deden belanden, waarbij het fragiele vertrouwen in ons rechtssysteem aan het licht kwam.

Consider the British Post Office scandal

and numerous cases featured on this homepage

and throughout the website;

they all serve as prime examples where everything

has gone wrong in terms of justice.

C. Clarification note

Raphael Rowe tells the story of

how he spent 12 years in prison

for crimes he did not commit.

Raphael is a clear indication or warning of something that is very wrong

in the justice system.

A Red Flag.

He was about 19.

Nobody wants to be fed lies. It’s better to be honest when you see how the justice system disfigures people by imprisoning them when they’re innocent.

When justice goes wrong, it goes quite wrong.

Notice the word ‘orchestrated’ in the 4 points at the top of the page.

Not only Raphael Rowe is a sign on the wall, all examples throughout the website are an indication and a serious warning.

Calling something like this an exception is wrong!

Transparency and truthfulness are crucial to prevent the injustice of imprisoning those who haven’t committed any crimes.

Niemand wil blaasjes wijsgemaakt worden. Je kan beter eerlijk zijn als je ziet hoe het justitie systeem mensen verminkt door ze onschuldig op te sluiten.

Als justitie in de fout gaat, gaat het behoorlijk fout.

Bemerk ‘orchestrated’ in de 4 punten bovenaan de webpagina.

Niet alleen Raphael Rowe is een teken aan de wand, alle voorbeelden doorheen de website zijn een indicatie en ernstige waarschuwing.

Het is fout zoiets een uitzondering te noemen!

Transparantie en waarachtigheid zijn cruciaal om te voorkomen dat onschuldige mensen worden opgesloten.

Trust is a judgement

that someone else can be relied upon or

that some institution can relied on.

It isn’t proof.

Trust is what we do when we need a shortcut.

Please listen to the BBC MP3 of philosopher, Onora O’Neill.

The big idea: the new distrust (about 10 minutes)

When you use justice in a negative way like in the cases of

John Bunn, Raphael Rowe, Liam Allan,

the list of 9 examples point 3 below, and so forth,

you automatically get such peculiar orchestrated results.

Wanneer je justitie op een negatieve manier gebruikt,

zoals in de gevallen van John Bunn, Raphael Rowe, Liam Allan,

de lijst van 9 voorbeelden point 3 below hieronder, enzovoort,

krijg je automatisch zulke eigenaardige georkestreerde resultaten.

D. No-nonsense

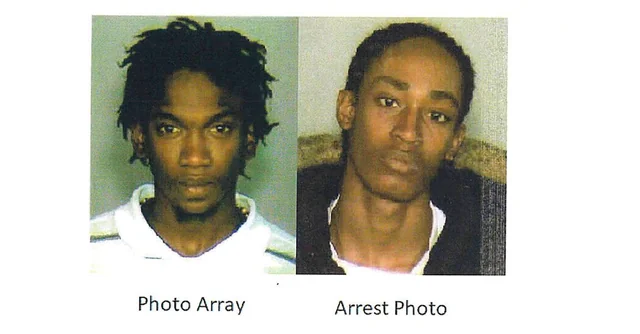

Sheldon Thomas was just 16

when he was convicted

on basis of a photo and

it was not him

december 2004.

19 year innocent in prison.

He was 35 when he came free.

Thomas was “denied due process at every stage.”

The case was based on 100% lies.

In the examples on this current page and throughout the website, we are continuously confronted with orchestrated, manipulated, or deceptive decisions without legality.

Authenticity: what’s real and what’s fake.

There are plenty of examples where justice is used as a toy, where justice fools someone.

It is all about dishonesty.

There is a problem, a big, big problem.

The way of looking at the justice system is not right, as explained in the above-mentioned explanation ‘The essence’.

In the reopened trial, the prosecution ruled that the police, prosecutors and judge of the original trial knew from the beginning that the photo in the sequence was not the Sheldon Thomas they arrested. Nevertheless, they went ahead. In addition, a group of 32 black law students examined the photo of Thomas. 27 students said, correctly, that the arrested Sheldon Thomas was not seen in the photos.

One can sabotage justice, even on a large scale, the case

The Post Office Wrongful Convictions Scandal

is exemplary. People know that the justice system is susceptible to fraud. This webpage and the entire website are living proof of that.

Furthermore, lower-standing database in point 3 with about 3500 examples of exonerated individuals with case descriptions and a brief summary at the top.

Among others, the Nijmegen-based Emeritus Professor of Philosophy of Science, Ton Derksen, who overturned the conviction of Lucia de Berk, after she had been wrongly imprisoned for 6 years, and is increasingly involved in revisions, uses the term judicial fraud and the pitfalls of truth-finding that underlie it.

Andrew Makinson – wrongly imprisoned for 17 years – unsafe conviction

In het heropende proces heeft de aanklager geoordeeld dat de politie, aanklagers en rechter van het oorspronkelijke proces vanaf het begin wisten dat de foto in de reeks niet de Sheldon Thomas was die ze hadden gearresteerd. Toch zijn ze doorgegaan. Bovendien heeft een groep van 32 zwarte rechtenstudenten de foto van Thomas onderzocht. 27 studenten zeiden terecht dat de gearresteerde Sheldon Thomas niet te zien was op de foto’s.

Men kan justitie saboteren, zelfs op grote schaal

The Post Office Wrongful Convictions Scandal

is desbetreffend exemplarisch. Men weet dat justitie fraudegevoelig is. Deze webpagina en de hele website is daarvan het levende bewijs.

Daarbij lagerstaande database in punt 3 met ongeveer 4500 voorbeelden van geëxoneerden met beschrijving van de zaak en korte samenvatting bovenaan.

O.a. de Nijmweegse Emeritus hoogleraar Wetenschapsfilosoof Ton Derksen die de veroordeling van Lucia de Berk ongedaan maakte, nadat ze al 6 jaar onterecht in de cel zat, en bij steeds meer herzieningen wordt betrokken gebruikt de term justitiefraude en de valkuilen van waarheidsvinding die daaraan ten grondslag liggen.

Andrew Makinson – wrongly imprisoned for 17 years – unsafe conviction

E. Slip through the cracks

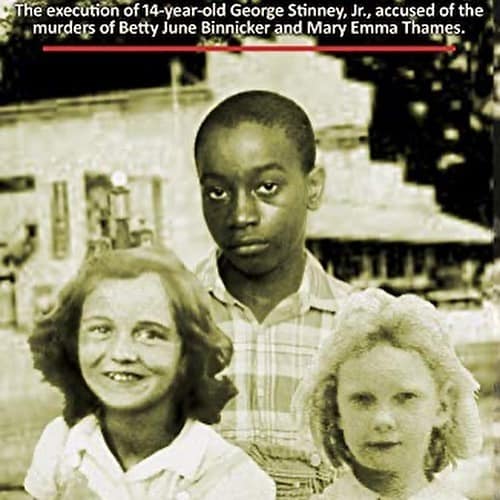

A 14-year-old child, ‘George Stinney’ (1944),

executed on the electric chair.

Without a speck of fairness.

It’s a hallmark of the the ‘power institution of justice’.

——–

In point ‘2: A Devilish Construction’ below, Louis Taylor,

a 16-year-old, went from being a hero to becoming

a scapegoat, spending 41 years in prison.

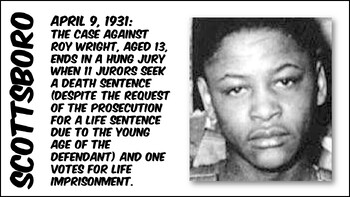

ON THIS DAY…March 25, 1931 The Scottsboro Boys were nine African American teenagers, ages 13 to 20, falsely accused in Alabama of raping two white women on a train in 1931. The landmark set of legal cases from this incident dealt with racism and the right to a fair trial. The cases included a lynch mob before the suspects had been indicted, all-white juries, rushed trials, and disruptive mobs. It is commonly cited as an example of a miscarriage of justice in the United States legal system.

Decisions are made based on ignorance. One cannot imagine it. It is incomprehensible.

Almost 100 years after ‘The Scottsboro Boys’ (1931), the justice system is still trapped in a wrong pattern. Even when everyone knows well what the undeniable reality is, an inherently wrong decision arises.

The harmony of the lives of children, young people, and individuals is, in an impossible and brutal manner, irreversibly altered in a single moment.

Even for the rest of their lives. From the splendor of life to hell in the blink of an eye. It’s an uncomfortable truth.

Men beslist op basis van onwetendheid. Men kan het zich niet voorstellen. Het is niet te begrijpen.

Bijna 100 jaar na ‘The Scottsboro Boys’ (1931) zit men bij justitie nog altijd vast in een fout patroon. Zelfs wanneer iedereen goed weet wat de onomstotelijke werkelijkheid is, onstaat er een intrinsiek foute beslissing.

De harmonie van het leven van kinderen, jongeren en mensen wordt op een onmogelijke wijze, brutaal, op een onherstelbare wijze, in één enkel ogenblik verandert.

Zelfs voor de rest van het leven. Van de glans van het leven bij het knippen van de vinger naar de hel. Het is een ongemakkelijke waarheid.

In a debate over the bill in April 2021, McKnight said he agreed with the death penalty in principle but that he opposed the state carrying out executions because of cases of people known to have been wrongfully executed or where there was significant doubt over their guilt.

George, who was Black, was put to death in 1944 (point E above) in the Jim Crow era of the South, after being accused of killing two white girls; Betty June Binnicker, 11, and Mary Emma Thames, 7.

The two girls are said to have been last seen while riding their bicycles in Alcolu, South Carolina, when they stopped to ask George and his younger sister Aime if they knew where they could find any maypops, the yellow fruit of passionflowers.

F. An Inconvenient Truth

In the coal mines of India, tens of thousands of children are forced to work in ‘rat holes’ – tiny pits too small for adults to reach.

Why are the authorities turning a blind eye to this lethal and illegal practice?

Please click (the link below the image), watch, and listen to the lives of these two young boys in a 22-minute video.

It captures a defining moment – the place where they belong.

Let children be children.

It’s about school with friends, their growth, and the education they deserve.

The Bible shockingly articulates

the uncomfortable truth of exploiting a child

(as in the video) through the metaphor of

a millstone around the neck

and being cast into

The link provides an overview of hundreds of web pages, subjects and themes.

It’s easy to browse through the website in this way.

De link geeft een overzicht van honderden webpagina’s, onderwerpen en thema’s.

Het is makkelijk om op deze manier doorheen de website te browsen.

The living conditions, housing,

and the reality for these two 12-year-old boys

working in Indian coal mines are appalling.

In other words, their situation is distressing

and shocking due to the harshness

of their work environment.

Please watch the video

It’s like what is depicted by the 12 links next to the image.

It’s like worthless legal decisions highlighted on the website.

Please reread the first three lines of point B above, considering the contents of this ‘Inconvenient Truth’.

Important link

The sheer brutality and inhumanity, representing the darkest facets of modern-day slavery, encapsulate the unfathomable injustice and pain inflicted upon Nsala and his family – a testament to the appalling atrocities committed by fellow humans in 1904. The passage highlights events that occurred during the exploitation era in Belgian Congo.

Which image is extremely strong?

While the the atrocities in the Congo Free State and subsequently in Belgian Congo remained hidden from the public eye until a few years ago, the flaws within courtrooms and halls of justice continue to stay concealed. Examples of egregious judicial failures are illustrated on this homepage and throughout the website.

Belangrijke link

De pure wreedheid en onmenselijkheid, die de donkerste facetten van moderne slavernij vertegenwoordigen, vatten het onpeilbare onrecht en de pijn samen die werden toegebracht aan Nsala en zijn familie – een bewijs van de verschrikkelijke wreedheden die in 1904 door medemensen werden begaan. De passage belicht de gebeurtenissen tijdens de uitbuitingsperiode in Belgisch Congo.

Which image is extremely strong?

Terwijl De wreedheden in de Congo Free State en daaropvolgend in Belgisch Congo tot voor enkele jaren verborgen bleef voor het grote publiek, blijft wat fout is in rechtbanken en justitiepaleizen verborgen. Voorbeelden van vreselijke mislukkingen van justitie worden geïllustreerd op deze homepage en door de hele website heen.

G. When ‘the veil of ignorance’ disappears

Exculpatory evidence

Evidence that supports a defendant’s innocence, which must be given to the defense by prosecutors unasked; if this rule is broken, the verdict could be overturned.

There is so much injustice in the justice system.

How to use “exculpatory evidence” in a sentence

- The defense lawyer strongly believes that the withheld surveillance footage is critical exculpatory evidence.

- The judge ordered the prosecution to provide all exculpatory evidence to the defense prior to trial.

- Overlooked exculpatory evidence was found which led to the defendant’s appeal for a new trial.

Deliberate mistakes

One can employ legal means to do wrong things

Particularly when it can disrupt society, irreversibly negatively affect the life of a child or young person, or impact the existential reality of a human life (as expressed in point e of this introduction in the text of 4 paragraphs, with the example of the Scottsboro Boys).

The use of the word ‘exception’ is incorrect

The disaster with The Herald of Free Enterprise in 1987 in Zeebrugge, The Fireworks Disaster in Enschede on Saturday, May 13, 2000, the initial verdict in The Rodney King Trial that led to the 1992 riots in Los Angeles, The Crash of Germanwings Flight 9525 on March 24, 2015, and similar incidents cannot be considered as exceptions.

Particularly, the 9 examples of an unjust conviction in the lower point 3 are also not an exception. As Barry Scheck put it in the case of Michael Morton, they were good lawyers. However, a prosecutor who withheld exculpatory evidence and was subsequently convicted for it. The difficulties faced by Belgian princess Delphine and The Chambermaid in the DSK Case, even though there was no doubt, are likewise not an exception.

It can happen that in your own environment, there are issues that closely resemble a pattern of what you see on the website, like two peas in a pod.

Justice experts, upright professionals, and profoundly knowledgeable individuals aware of the failures within the justice system and the shocking consequences thereof, as evidenced by examples on this webpage and throughout the website, openly acknowledge what is at hand.

You can’t fool anyone.

It occurs that a blatant and clear deceptive construction has been put in place.

This aligns with thousands of cases of exonerated individuals where, in hindsight, after decades, it becomes evident that an unquestionably erroneous verdict was rendered, one that cannot be overlooked.

An orchestrated, manipulated, or deceptive incident has taken place.

When this happens to oneself or when it affects the innocence of a child, causing unbearable pain as seen in numerous examples, an insurmountable existential issue arises.

Het kan gebeuren dat in je eigen omgeving, er kwesties zijn die als twee druppels water gelijken op een patroon van wat je in de website ziet.

Justitie-experts, integere professionals en ernstig onderlegde personen met kennis van het falen van justitie en de schokkende gevolgen daarvan, zoals voorbeelden op deze webpagina en doorheen de website, erkennen openlijk wat er aan de hand is.

Men kan geen blaasjes wijsmaken.

Het komt voor dat er flagrant en duidelijk een bedrieglijke constructie in elkaar is gezet.

Dit komt overeen met duizenden gevallen van geexonereerde personen waarbij achteraf, na tientallen jaren, blijkt dat er een onomstotelijk foutief vonnis is geveld, waar men onmogelijk aan voorbij kan gaan.

Er heeft een georkestreerd, gemanipuleerd of bedrieglijk incident plaatsgevonden.

Wanneer dit jezelf overkomt of wanneer het de onschuld van een kind treft en ondraaglijke pijn veroorzaakt, zoals in vele voorbeelden, dan ontstaat er een onoverkomelijke existentiële kwestie.

Labeling the two Boeing 737 Max crashes as exceptions is incorrect, as it is argued that a plane crash usually involves a combination of causes, with backup systems in place for various scenarios. However, this wasn’t the case for the Boeing 737 Max concerning the crash’s cause. Furthermore, the entire system used to certify the aircraft was fundamentally flawed for the Boeing 737 Max.

The two fatal crashes involving the Boeing 737 Max occurred in October 2018 and March 2019.

These events point to larger systemic issues

rather than being isolated anomalies.

It highlights their importance in understanding

broader patterns or problems

within their respective contexts.

Wrongful convictions are rather

symptomatic of larger problems

within the justice system.

Deze gebeurtenissen wijzen op grotere systemische problemen

in plaats van geïsoleerde anomalieën te zijn.

Het benadrukt hun belang in het begrijpen van

bredere patronen of problemen

binnen hun respectieve contexten.

Ten onrechte veroordelingen zijn eerder

symptomatisch voor grotere problemen

binnen het rechtssysteem.

Systemic

Formal

A systemic problem or change is a basic one, experienced by the whole of an organization or a country and not just particular parts of it.

The current recession is the result of a systemic change within the structure of the country’s economy.

Adjective

Relating to or involving a whole system.

The problems are systemic and will only worsen.

Cambridge Dictionary

Justice demands honesty,

as evidenced by the points on this initial webpage.

Take, for instance,

The Post Office Wrongful Convictions Scandal,

where over 730 individuals were wrongly convicted,

hundreds accepted settlements, and some even took their own lives.

Ultimately, the highest court in the UK ruled in a damning manner,

considering that the true issue had been well-known since the very beginning (2007).

They lied persistently, deceiving hundreds of people whose lives were shattered. And so on…

‘Miscarriage of justice’ as thousands of UK post workers falsely accused of fraud: Thousands of post office workers in the U.K. were falsely accused of accounting fraud–all because of a faulty computer system. Hundreds were falsely convicted, while many more lost their savings. Four committed suicide. Now, a new drama on the British channel ITV exposed the scandal and prompted the U.K. government to try to make amends.

When the system fails, you end up in nothing short of Modern Day Slavery.

H. To put a spoke in someone’s wheel

The right place at the right time. Juan Catalan spent nearly 6 months in jail for the murder of a teenage girl until his lawyer found unused footage from HBO’s ‘Curb Your Enthusiasm’ -that proved he’d been at a Dodger’s game with his 6-year-old daughter.

No matter how innocent you are. No matter how clear it is that you had nothing to do with it. And that you weren’t even there when something happened. Even if your entire life history shows that you cannot be labeled as a bad person, nothing helps when you end up in a deceitful justice system.

Like in the case of Julan Catalan, who spent 6 months in prison. This was his fate for the rest of his life. It’s coincidence, one in a million, that saved him. Something like that has nothing more to do with a justice system.

The impossibility of proving your innocence!

With a false testimony and a construction fabricated by 2 LAPD cops, Juan Catalan is framed at the scene of the murder.

How do you prove that you weren’t there at the time of the murder? It’s impossible to counter that.

The coincidence of being filmed at the baseball game station with 56,000 spectators, at the place where Juan Catalan was with his little daughter, and exactly at that moment.

By contacting the cellphone provider and pinpointing the cell tower near Dodger Stadium that Juan’s phone was pinging, as well as researching Juan’s calls with his girlfriend Alma that evening, the lawyer Melnik was able to determine that Juan was still at the stadium at 10:12 p.m.

Juan Catalan narrowly escapes trouble with the exceptional dedication of his lawyer. Saved From Crooked Cops and Lying Prosecutor.

The president of Duke University offers an apology for the handling of the Lacrosse scandal.

De onmogelijkheid om je onschuld te bewijzen!

Met een vals getuigenis en een constructie gefabriceerd door 2 LAPD cops wordt Juan Catalan geframed op de plaats van de moord.

Hoe bewijs je dat je daar niet was op het moment van de moord? Het is onmogelijk daar tegen op te tornen.

Het toeval dat er gefilmd wordt in het baseball game station met 56 000 toeschouwers, op de plaats waar Juan Catalan met zijn dochtertje was én precies op dit moment.

Door contact op te nemen met de mobiele provider en de zendmast in de buurt van Dodger Stadium te lokaliseren waar Juan’s telefoon contact mee maakte, en door het onderzoeken van Juan’s gesprekken met zijn vriendin Alma die avond, slaagde advocaat Melnik erin vast te stellen dat Juan om 22:12 uur nog steeds in het stadion was.

Juan Catalan kruipt door het oog van een naald met behulp van de uitzonderlijke inzet van zijn advocaat. Gered van corrupte agenten en liegende aanklager.

De president van de Duke University biedt excuses aan voor de afhandeling van het Lacrosse-schandaal.

The Guildford Four,

The Birmingham Six – 1974 – Who cares?,

Two cases in Great Britain where practices were employed that one cannot fathom, resulting in the wrongful imprisonment of innocents for 15 years.

In the case of The Birmingham Six, Prime Minister Tony Blair had to publicly apologize for the injustice caused by the judiciary.

Saint Omer, near Calais in northern France.

In the Saint Omer case, 17 people were imprisoned for 4 years based on one person giving false testimony.

The case became known as ‘The Birmingham Six of France.

When there are indications that the justice system is failing,

it is essential to approach the situation with caution.

——–

At times, one may observe actions that appear orchestrated

or even blatantly deceitful.

——–

Filing a lawsuit without grounds is a clear ‘Red Flag.’

Justice is not a fairy tale.

Examining cases where justice seems to falter,

or where its application is unexpected

or controversial,

can inspire thought-provoking discussions.

I. The goose that lays the golden eggs

1 Reactions Of INNOCENT Convicts SET FREE!

This channel will highlight the best courtroom moments, from courtroom chaos to enraged judges. This video is inspired by Court Cam and 60 Days In

The videos you’ll see here are in documentary text content of what happens in the courtroom and what happens leading up to it while also breaking down each scene in each video in extreme detail.

If you are or represent the copyright owner of materials used in this video and have a problem with the use of said material, please send an email to courtroomchannel@gmail.com and we can sort it out. Some original clips may be edited and trimmed down. This video is not legal advice. This video is for entertainment purposes only.

0:00 John Bunn

1:09 David Ranta

2:45 Susan Mellen

4:05 Luis Vargas

5:14 Daniel Villegas

6:44 Ricky Jackson

8:11 Kirstin Lobato

2 apr 2023

For copyright matters, please contact: juliabaker0312@gmail.com

Welcome to the Discoverize! Here, we dive into the most exciting and unbelievable things that the world has to offer. From ancient artifacts to mind-blowing scientific theories, there’s never a dull moment on our channel. Join us as we embark on a thrilling journey of discovery and wonder, and get ready to have your socks knocked off by the amazing things that we uncover. Whether you’re a lifelong learner or just looking for a good time, our channel is sure to entertain and educate. Buckle up and get ready for an unforgettable ride!

A Belgian appeals court has ruled that former King Albert II is to be fined €5,000 (£4,370) a day if he refuses to undergo a DNA test.

La journée noire de Dominique Strauss-Kahn

Similar to numerous instances highlighted on this homepage and across the website, there’s a trend where issues considered ‘indisputable and beyond question’ lead to an artificial construct within the realm of justice – a detached ivory tower, removed from life’s simple realities.

Put simply, much like the earlier point: Juan Catalan fell victim to elements within the justice system, enduring a 6-month prison sentence until lawyer Melnik unravelled the intricately woven web, akin to finding a needle in a haystack.

This serves as an example where financial resolution seems unattainable. Yet, akin to the Good Samaritan, the lawyer undertook what was necessary, ultimately resolving the case.

Another illustration lies in the case involving Belgian Princess Delphine versus King Albert II, a legal battle spanning approximately 20 years, involving 7 years in court. Albert II even appealed to the highest court twice and adamantly refused to provide his DNA until the court imposed a 5000 euro daily fine for non-compliance. It wasn’t until this penalty was enforced that a swift resolution emerged, despite Albert II’s legal team’s desire to prolong proceedings.

In essence, justice becomes akin to

a goose laying golden eggs,

an asset lawyers are reluctant to sacrifice,

artificially prolonging cases for financial gain.

Likewise, we can observe a similar situation in the well-known case involving DSK at the Sofitel Hotel in New York. Private detectives were employed as a deus ex machina, fabricating an artificial portrayal of the chambermaid, aimed at securing DSK’s release from prison. This incident prolonged for a total of 98 days. Subsequently, in a civil proceeding, DSK opted for a settlement, implying an acknowledgment of guilt, mirroring the case of King Albert II, where justice was seemingly manipulated in an entirely contrived manner.

Zoals in talloze voorbeelden op deze home pagina en doorheen de website, gebeurt het dat in kwesties die “absoluut duidelijk zijn, die niet kunnen onkent worden en niet kunnen in vraag gesteld worden” dat je bij justitie in een kunstmatige wereld terecht komt, de ivoren toren, wereldvreemd tegenover de eenvoudige werkelijkheid van het leven.

M.a.w. zoals in het vorige punt: Juan Catalan werd bedrogen door entiteiten binnen justitie, zat daardoor 6 maanden in de gevangenis en het was door de advocaat Melnik dat de kunstmatig in elkaar gestoken verwarde knoop ontward werd als de spelt in de hooiberg.

Dit is een van de voorbeelden die financieel onmogelijk op te lossen zijn, doch als de barmhartige samartitaan heeft deze advocaat gedaan wat nodig was en de zaak werd opgelost.

De lagerstaande kwestie van de Belgische Princes Dellphine tegenover koning Albert II, die ongeveer 20 jaar heeft aangesleept, waarvan 7 jaar in de rechtbank, waarbij Albert II zelfs tweemaal in cassatie gaat en weigert zijn DNA af te staan, tot de rechtbank een dwangsom oplegt van 5000 euro per dag dat Albert II weigert zijn DNA af te staan en dan is alles onmiddellijk opgelost. Rekening houdend dat zelfs dan nog de advocaten van Albert II nog wilden verderdoen.

M.a.w. justitie staat gelijk aan

de kip met de gouden eieren

die advocaten niet willen slachten,

om op een kunstmatige manier het geld binnen te rijven.

Idem heb je ook de lager staande kwestie van DSK in het Sofitel Hotel in New York. Privédetectives die als deus ex machina gebruikt worden om een kunstmatig beeld te creëren van het kamermeisje, om op die manier DSK vrij te krijgen uit de gevangen. Een kwestie die uiteindelijk 98 dagen heeft geduurd. In een burgerlijke procedure is DSK dan tot een schikking is gekomen, m.a.w. de schuld van het misdrijf staat vast, net zoals in het gebeuren van Koning Albert II die justitie op een totaal kunstmatige manier heeft gebruikt.

“DSK Maid” Tells of Her Alleged Rape by Strauss-Kahn: Exclusive

‘To see the speck in another’s eye, but not the beam in one’s own’.

J. The red line or

the line in the sand

Convicted at 21, and still locked up at 49, Lamar Johnson has spent most of his life in prison for a crime he did not commit.

Both the former prosecutor and police detective leading Johnson’s case testified they had no evidence connecting Johnson to the murder. The conviction rested solely on Elking picking Johnson out of a lineup based upon Elking’s memory of seeing the masked gunman’s eyes for a few seconds — and it took Elking four times of viewing the same lineup to do it.

“You had a witness in this case who told you…at best he could recognize maybe something about the eyes,” Mason said to former detective Joseph Nickerson during the December hearing. “Are you sure this isn’t a situation where you guys were in a little bit of a rush to make a conviction?”

Please listen to video’s about the case Lamar Johnson

Wrongful convictions and miscarriages of justice are tragic examples of the flaws or misuse of the justice system.

Sometimes, due to various reasons such as flawed evidence, bias, procedural errors, or even intentional malpractice, innocent individuals can be wrongfully convicted and imprisoned for crimes they didn’t commit.

These cases highlight the complexity and imperfections within the justice system. The phrase “Justice Is a Two-Edged Sword” can apply here, illustrating how justice, when applied incorrectly or through flawed processes, can bring about severe harm and suffering to innocent individuals.

It showcases the dual nature of justice, where its application can have both positive outcomes when rightly served and devastating consequences when applied erroneously or unfairly.

Wrongful convictions underscore the importance of ensuring fair trials, proper investigation, unbiased proceedings, and continuous efforts to prevent and rectify miscarriages of justice. It’s a poignant reminder of the need for constant vigilance and improvement within legal systems to mitigate such injustices.

In Lamar Johnson’s case, reliance on eyewitness accounts was crucial, yet the circumstances, including the shooting in darkness and the perpetrators wearing masks, cast doubt on the accuracy of identifications. Complicating matters, an eyewitness later recanted, adding complexity. Johnson offered an alibi, presenting multiple facets for the jury to consider.

In het geval van Lamar Johnson was het sterk leunen op ooggetuigenverslagen essentieel, maar de omstandigheden, waaronder de schietpartij in het donker en de daders die maskers droegen, brachten twijfel over de nauwkeurigheid van de identificaties. Het werd ingewikkelder doordat een ooggetuige later zijn verklaring introk, wat complexiteit toevoegde. Johnson presenteerde een alibi en bood meerdere facetten aan de jury ter overweging.

K. The arc of the moral universe

will bend toward justice – but only if we pull it

You are 29 and without any data you spend 28 years in prison.

Shortly after his arrest, Detective Doug Acker told Hinton,

“I don’t care whether you did or didn’t do it. In fact,

I believe you didn’t do it. But it doesn’t matter.

If you didn’t do it, one of your brothers did.

And you’re going to take the rap.”

“I can give you five reasons why they are going to convict you.

- Number one, you’re black.

- Number two, a white man gonna say you shot him.

- Number three, you’re gonna have a white district attorney.

- Number four, you’re gonna have a white judge.

- And number five, you’re gonna have an all-white jury.”

In what precedes, we have a series of examples where the justice system shows an incredibly difficult course, despite the fact that in all these examples, the individuals mistreated by the justice system cannot be linked to what is happening. It is remarkable what is happening within the justice system.

Throughout the entire course of such a legal affair, numerous complications can arise, causing furrowed brows, ultimately resulting in someone who knows nothing about it being put in great difficulty.

In wat vooraf gaat hebben we een reeks voorbeelden waar justitie een onvoorstelbaar moeilijk verloop vertoont, ondanks in al deze voorbeelden de personen die door justitie fout behandeld worden, niet in verband kunnen gebracht worden met wat er aan de hand is. Het is merkwaardig wat er bij justitie gebeurt.

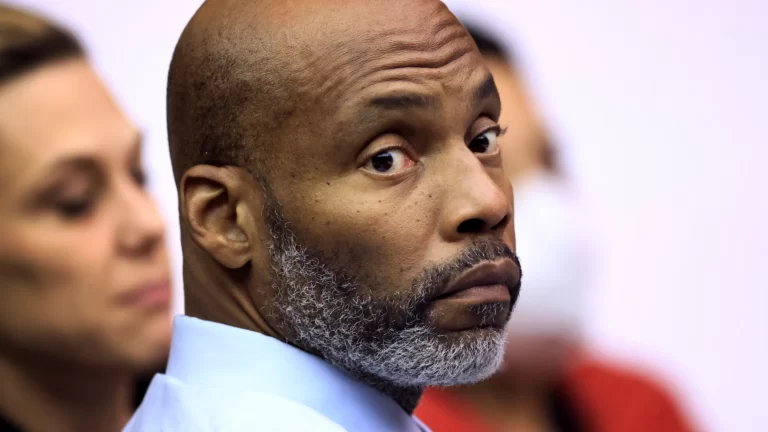

Anthony Ray Hinton (born June 1, 1956) was wrongly convicted of the 1985 murders of two fast food restaurant managers in Birmingham, Alabama. Hinton was sentenced to death and held on the state’s death row for 28 years before his 2015 release.

In 2014 the Supreme Court of the United States unanimously overturned his conviction on appeal, after which the state dropped all charges against him. The court was unable to affirm the forensic evidence of a gun, which was the only evidence in the first trial. After being released, Hinton wrote and published a memoir The Sun Does Shine: How I Found Life and Freedom on Death Row (2018). Hinton was portrayed by O’Shea Jackson Jr. in the 2019 film Just Mercy.

L. Bread and Circuses

There was a significant scandal involving the British Post Office known as the “Post Office Horizon IT Scandal.”

In this scandal, subpostmasters were wrongly accused of theft, fraud, and false accounting due to issues with the Horizon accounting system, which was used by the Post Office.

The Horizon system, introduced in the early 2000s, had software glitches that led to discrepancies in accounting records. Many subpostmasters faced financial losses, bankruptcy, and legal troubles as a result of being held responsible for these discrepancies. The scandal came to light, and there were efforts to review and rectify the unjust convictions.

Subsequently, in 2021, the UK Court of Appeal overturned the convictions of many subpostmasters, acknowledging the flaws in the Horizon system and the impact on these individuals’ lives. The scandal highlighted concerns about the use of technology in legal matters and the need for a fair and just system.

De Britse Post Office-affaire, ook bekend als de “Post Office Horizon IT Scandal”, betrof onterechte beschuldigingen aan het adres van subpostmasters voor diefstal, fraude en valse boekhouding als gevolg van problemen met het Horizon-boekhoudsysteem dat door de Britse Post Office werd gebruikt.

Het Horizon-systeem, geïntroduceerd in het begin van de jaren 2000, vertoonde softwarefouten die tot onregelmatigheden in de boekhoudgegevens leidden. Veel subpostmasters leden financiële verliezen, gingen failliet en kregen juridische problemen doordat ze verantwoordelijk werden gehouden voor deze onregelmatigheden. Het schandaal kwam aan het licht, en er waren inspanningen om de onrechtvaardige veroordelingen te herzien en recht te zetten.

In 2021 heeft het Britse Hof van Beroep de veroordelingen van veel subpostmasters vernietigd, waarbij erkend werd dat er gebreken waren in het Horizon-systeem en dat dit ernstige gevolgen had gehad voor het leven van deze personen. Het schandaal bracht zorgen aan het licht over het gebruik van technologie in juridische zaken en de noodzaak van een eerlijk en rechtvaardig systeem.

LIFE IS NOT EASY!

HOW TO HANDLE AN EXCEPTIONAL SITUATION?

3 Chocolate Milkshake: The Power of Hope

2 Post Office scandal: Fujitsu staff knew about bugs, errors and defects in the system for years

Back to menu IMPORTENT CONTENT Listening recommended Must ***

19 jan 2024

The European boss of Fujitsu has admitted the company “clearly let society down” as he apologised again to subpostmasters and postmistresses over its role in the Horizon scandal.

Giving evidence to the public inquiry, Paul Patterson said Fujitsu staff had known about bugs, errors and defects in the system for years – but claimed the firm only became aware “latterly” that faulty data was being used in prosecutions.

Doomed from the very start, which was known by all parties

At minute 4: armed with all the knownledge, why not shoot it of the roof tops?

At minute 5: a massive cover up

At minute 6: alerted insurers in 2013, stopped prosecutions in 2014

At minute 7: a lot more than just money

- The Great British Post Office Wrongful Convictions Scandal is a kind of Candid Camera set in real life.

- A false image is deliberately created to falsely accuse people.

- Playing up appearances. An artificial event.

- In reality, it is internet problems that cause transactions to be lost.

- Het grote Britse postkantoorschandaal met onterechte veroordelingen is een soort Candid Camera die zich in het echte leven afspeelt.

- Op een bewuste wijze wordt een verkeerd beeld gecreëerd om mensen vals te beschuldigen.

- Het spelen van de schone schijn. Een kunstmatig gebeuren.

- In werkelijkheid zijn het internet problemen die oorzaak zijn dat transacties verloren gaan.

Please listen to more video’s by Bryan Stevenson

4 Falsely Accused Former Postmasters: ‘Money Doesn’t Come with an Erase Button.’| Good Morning Britain

Back to menu IMPORTENT CONTENT Listening recommended Must ***

11 jan 2024

Parmod Kalia and Janet Skinner were both wrongly convicted following false accusations of stealing thousands of pounds from their respective post offices. Despite having their convictions quashed in 2021 they are still waiting for compensation.

Former Postmaster Parmod Kalia was sentenced to six months in jail after being falsely accused of stealing £22,000.

Former sub-postmaster Janet Skinner served three months of a nine-month sentence in prison after being falsely accused of stealing almost £60,000 from the Post Office she ran.

Broadcast on 11/01/24

Both 3 months in prison

5 Post office inquiry: Fujitsu manager called bankrupted subpostmaster ‘nasty chap’

18 jan 2024

A Fujitsu employee called a subpostmaster who was bankrupted by the company’s faulty computer system a “nasty chap” in not-seen-before email sent internally in 2003.

Peter Sewell, who was in the Post Office Account Security Team at Fujitsu, said that Lee Carrington was a “nasty man” after the subpostmaster had threatened the company with legal action after losing all his money due to no fault of his own.

Fujitsu provided the Post Office with the Horizon computer system for individual subpostmasters. This system wrongly said that hundreds of subpostmasters had been committing fraud and more than 700 were wrongly convicted.

The email was revealed at the ongoing Post Office Horizon Inquiry.

A culture of

‘hanging someone out to dry’

prevailed in the British Post Office

during the IT Horizon scandal,

where victims were wrongly prosecuted over many years.

The Post Office lied on an industrial scale to ministers,

resulting in a total mess.

The strategy is made clear e.g. in the email from Peter Sewell,

a Fujistu boss, to Andy Dunk,

the witness for the court,

with the pep talk about Lee Caslteton which

he called a nasty chap, and the answer from Dunks:

“Thank you for those very kind and encouraging words.

I had to pause halfway through reading it to wipe away a small tear.“

Hang someone out to dry:

To allow someone to be punished, criticized,

or made to suffer in a way that is unfair, without trying to help them.

Please listen to video 5 above ‘Post office inquiry:

Fujitsu manager called bankrupted subpostmaster ‘nasty chap’

The video reveals an

appalling and shameful

attitude exhibited by Peter Sewell.

There is one rule in this country for those in power

and another for those who don’t have it.

The Post Office Scandal is deeply instructive

regarding the organization of our society

for both those who possess power

and those who lack it.

6 Labour MP corners Post Office bosses over dodgy bonus culture in fiery Select Committee exchange

Back to menu IMPORTENT CONTENT Listening recommended Must ***

Head honchos at the Post Office and members of their remuneration committee were in front of the Business and Trade Select Committee on Tuesday, where chair of the Committee Darren Jones absolutely rinsed them over an apparent breach of rules related to the awarding of bonuses – which can lead to years in jail if found guilty.

1. The poor – work & work.

2. The rich – exploit the poor.

3. The soldier – protects both.

4. The taxpayer – pays for all three.

5. The banker – robs all four.

6. The lawyer – misleads all five.

7. The doctor – bills all six.

8. The goons – scare all seven.

9. The Politician – lives happily

on account of all eight.

Written in 43 B.C. Valid even today!

7 Former Fujitsu manager calls errors a ‘contractual problem’ in Post Office scandal inquiry

Back to menu IMPORTENT CONTENT Listening recommended Must ***

10 jan 2024

Iain Dale and his Cross Question panel discuss what’s next for the Post Office scandal after the company’s former boss, Paula Vennells, announced she’d be handing back her CBE with immediate effect.

Our Cross Question panel: Mims Davies (Minister for Disabled People, Health and Work, and Conservative MP for Mid Sussex), Darren Jones (Shadow Chief Secretary to the Treasury and Labour MP for Bristol North West), Emma Sinclair (Tech entrepreneur – who is the chief executive of EnterpriseAlumni), Oli Dugmore (Head of News and Politics at JOE Media, and LBC presenter).

8 Post Office scandal is ‘deeply instructive’ about how the UK works | LBC debate

Back to menu IMPORTENT CONTENT Listening recommended Must ***

10 jan 2024

Iain Dale and his Cross Question panel discuss what’s next for the Post Office scandal after the company’s former boss, Paula Vennells, announced she’d be handing back her CBE with immediate effect.

Our Cross Question panel: Mims Davies (Minister for Disabled People, Health and Work, and Conservative MP for Mid Sussex), Darren Jones (Shadow Chief Secretary to the Treasury and Labour MP for Bristol North West), Emma Sinclair (Tech entrepreneur – who is the chief executive of EnterpriseAlumni), Oli Dugmore (Head of News and Politics at JOE Media, and LBC presenter).

In April 2021, the Court of Appeal quashed the convictions of 39 former Subpostmasters and ruled their prosecutions were an affront to the public conscience. They were just a few of the hunderds who had been prosecuted by the Post Office using IT evidence from an unreliable computer system called Horizon.

When the Post Office became aware that Horizon didn’t work properly, it covered it up.

The Great Post Office Scandal is the Story of how these innocent people had their lives ruined by a once-loved national institution and how, against overwelming odds, they fought back to clear their names. The fight to expose a multimillion Pound IT disaster which put innocent people in jail.

Gripping, heart-breaking and enlighening, The Great Post Office Scandal by Nick Wallis should be read by everyone who wants to understand how this massive miscarriage of justice was allowed to happen.

An extraordinary journalistic exposé of a huge miscarriage of justice.

Nick’s narrative has the power of a great thriller as he lays bare the lies and deceit that has ruined so many lives.

A tale brilliantly told by Nick Wallis, who has dedicated years of work to establishing what happened, why it happened, and calling those responsible to account. I urge you to read it.

In april 2021 heeft het Hof van Beroep de veroordelingen van 39 voormalige Subpostmasters vernietigd en geoordeeld dat hun vervolgingen een affront waren voor het publieke geweten. Ze waren slechts enkelen van de honderden die vervolgd waren door het Postkantoor op basis van IT-bewijs van een onbetrouwbaar computersysteem genaamd Horizon.

Toen het Postkantoor zich ervan bewust werd dat Horizon niet goed werkte, heeft het dit verdoezeld.

Het Grote Postkantoor Schandaal is het verhaal van hoe deze onschuldige mensen hun levens verwoest zagen door een eens geliefde nationale instelling en hoe ze, tegen overweldigende kansen in, terugvochten om hun namen te zuiveren. De strijd om een IT-fiasco van miljoenen ponden bloot te leggen dat onschuldige mensen in de gevangenis bracht.

Meeslepend, hartverscheurend en verhelderend; The Great Post Office Scandal by Nick Wallis zou gelezen moeten worden door iedereen die wil begrijpen hoe deze enorme gerechtelijke dwaling kon plaatsvinden.

Een buitengewoon journalistiek exposé van een groot gerechtelijk falen.

Nick’s verhaal heeft de kracht van een geweldige thriller terwijl hij de leugens en bedrog blootlegt die zoveel levens hebben verwoest.

Een briljant verteld verhaal door Nick Wallis, die jarenlang werk heeft toegewijd aan het vaststellen van wat er is gebeurd, waarom het is gebeurd, en het verantwoordelijk houden van degenen die ervoor verantwoordelijk zijn. Ik dring er bij je op aan om het te lezen.

M. Blinded and Derailed

The unimaginable large-scale event, ‘The Post Office Wrongful Conviction Scandal,’ is a prime example of what can happen in a society.

Out of nowhere, like a bolt from the blue, 730 people in the United Kingdom – each responsible for their respective post office – were convicted of theft, even though everyone knew they were innocent.

The flawed technology of the Horizon IT project was the culprit behind lost transactions, resulting in discrepancies in the postmaster’s accounting at the end of the day. In 1999, the UK implemented an IT project that computerized the post offices.

In clear language, one can say that it can happen to anyone that justice suddenly, without reason, cause, or basis, determines your life, despite there being nothing to be noted about you.

This is what happened suddenly to 19-year-old Liam Allan as a university student. A minute before twelve, he narrowly escaped a 10-year prison sentence and a lifetime branded as a dangerous sexual delinquent.

The website paints a picture of a kind of justice as an artificial context in which the innocent are consciously shattered by being imprisoned without the slightest fair judicial process, with no hope of ever being free again.

In klare taal kan men zeggen dat het iedereen kan overkomen dat justitie plotseling, zonder reden, aanleiding of oorzaak, je leven bepaalt, ondanks dat er niets op je is aan te merken.

Dit is wat de 19-jarige Liam Allan plotseling overkwam als universiteitsstudent. Een minuut voor twaalf ontsnapte hij ternauwernood aan een 10 jaar durende gevangenisstraf en een leven lang gebrandmerkt te worden als gevaarlijke seksuele delinquent.

De website schetst een beeld van een soort justitie als een kunstmatige context waarin onschuldigen bewust worden verbrijzeld door hen zonder het minste eerlijke verloop van justitie op te sluiten, zonder hoop om ooit nog vrij te komen.

It is revolting;

in all cases,

there is absolutely nothing,

no data whatsoever,

no matter how you look at it,

no connection or indication whatsoever.

It is clearly wrong,

and yet the blame is placed on you,

even though everyone knows how it all fits together

or what the cause is.

According to a specific pattern,

deceptive methods are used

to create a false impression.

The flawed technology of the Horizon IT project

in The Post Office Wrongful Conviction Scandal

is a prime example of

how justice can be wrongly employed

to crush the innocent.

The layers of complexity

There is nothing wrong,

but you find yourself in an artificial legal context.

Taken for a ride by the justice system

In the listed examples, a photo is used, but you are not the person in the photo.

(The case of Sheldon Thomas, who was sentenced to 19 years in prison at the age of 16).

You were not at the crime scene but at a sports event with more than 50,000 spectators

and your phone conversation is intercepted in the vicinity of the stadium.

Yet, you get into trouble until coincidental film footage emerges, taken at the actual location where you were.

(The case of Juan Catalan: Saved from Crooked Cops and a Lying Prosecutor).

Another example involves a so-called witness being pressured.

However, the perpetrator could not be identified because he was masked.

Therefore, claiming that the perpetrator was recognized is pointless.

(The case of Lamar Johnson, a 21-year-old who was locked up for 28 years).

This is what happened to John Bunn.

He was at home sleeping at 4 o’clock in the morning,

and, knowing he was innocent,

he was imprisoned for 17 years due to corrupt cop Louis Scarcella

(see the link to the first video: Top 7 Reactions Of INNOCENT Convicts Set Free).

Similar incidents happened to the other 6 people in the video.

On the other hand, a decision cannot be made based on something one does not know,

or creating an image of a person with an attitude and behavior that is not at all consistent with the person you are.

“Taken for a ride by the justice system”

conveys the idea that someone feels deceived or mistreated by the legal system.

It suggests a sense of being manipulated or experiencing unfair treatment

within the context of the justice system.

The Dutch expression

“Erin geluisd worden”

can be roughly translated to English as