Satan before the Lord

Page Description

Devil’s advocate:

a person who expresses a contentious opinion

to provoke debate

or test the strength of opposing arguments

Challenging the Truth or Distorting It?

The Devil’s Advocate – a phrase often associated with challenging prevailing beliefs, questioning assumptions, and defending the unpopular. Originally a formal role in the Catholic Church, the advocatus diaboli was tasked with arguing against the canonization of a saint, ensuring that claims of virtue were thoroughly examined. Today, the term extends beyond religious contexts, representing those who provoke debate, expose weaknesses in arguments, and push for deeper scrutiny—sometimes for truth, sometimes for strategy. But when does playing the devil’s advocate serve justice, and when does it become a tool for manipulation?

De waarheid uitdagen of verdraaien?

De advocaat van de duivel – een term die vaak wordt geassocieerd met het uitdagen van gevestigde overtuigingen, het bevragen van aannames en het verdedigen van het onpopulaire. Oorspronkelijk was de advocatus diaboli een formele functie binnen de Katholieke Kerk, bedoeld om heiligverklaringen kritisch te toetsen. Tegenwoordig reikt de betekenis verder dan religieuze contexten en verwijst het naar degenen die debat uitlokken, zwakke plekken in argumenten blootleggen en aanzetten tot diepere analyse – soms in de naam van de waarheid, soms als strategie. Maar wanneer dient het spelen van de advocaat van de duivel de rechtvaardigheid, en wanneer wordt het een instrument van misleiding?

Devil’s advocate: a person who expresses a contentions opinion in order to provoke debate or test the strength of the opposing arguments.

Someone who pretends, in an argument or discussion, to be against an idea or plan that a lot of people support, in order to make people discuss and consider it in more detail:

I don’t really believe all that – I was just playing devil’s advocate.

Cambridge Dictionary

DEVIL’S ADVOCATE

Sometimes it is said that someone is playing devil’s advocate. This means that someone deliberately shows the negative side of a case or tries to defend the side of the opponent. People sometimes play devil’s advocate to make others think. Sometimes it seems very logical that someone is right, but if you turn the matter around, the other person may also be right. That is not always a nice thing to realise. Try playing devil’s advocate when you have an argument with someone or disagree with someone. Try to think why the other person might be right, or why they might be angry with you.

Every criminal has the right to a lawyer. So the greatest villain of all, the devil, should also have a lawyer.

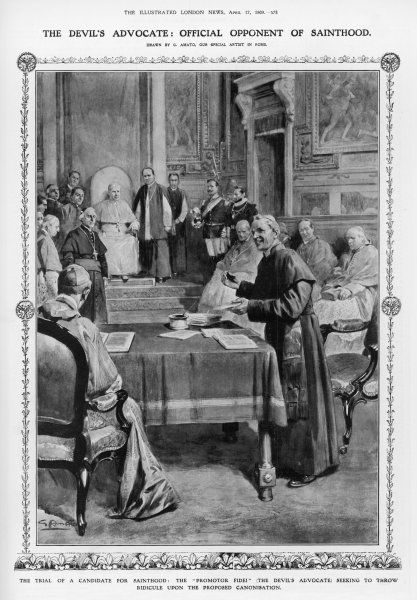

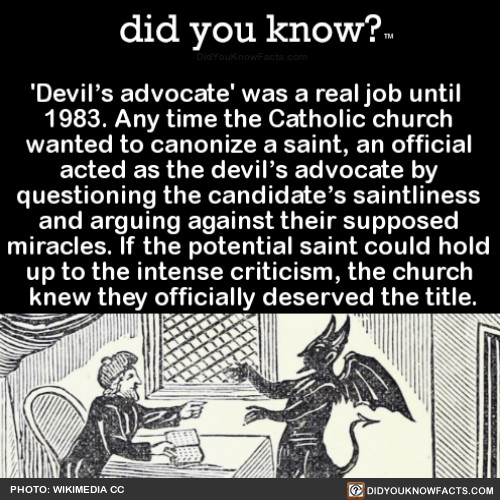

In the Catholic Church, before someone was canonised by the Pope, a lengthy process had to take place in Rome. There was also an opponent: the devil’s advocate. He would come up with all kinds of arguments why the future saint should not be called holy.

Where does the expression devil’s advocate come from and what does it mean?

When you play devil’s advocate, you act like a pessimist during a meeting or discussion: you ask critical questions and make comments and remarks from as negative a position as possible. This is often done to check whether all the drawbacks of a plan have been properly mapped out, or to get a picture of what could go wrong.

You can also be explicitly asked to play devil’s advocate in a discussion. Or you can say: “I’m playing devil’s advocate here. You can then defend a point of view (which you may not even support yourself) that goes completely against the other person’s point of view. It is a way to enliven the discussion or to teach the discussion partners how to argue.

The devil’s advocate is actually the person who, during beatifications and canonisations in the Roman Catholic Church, asks critical questions about the sanctity of the candidate. A kind of trial is staged in which it is examined whether this candidate is really worthy of being beatified or canonised. According to the Dutch dictionary Groot Uitdrukingenwoordenboek van Van Dale (2006), the devil’s advocate (advocatus diaboli) has the task of raising objections against the candidate. The advocate of God (advocatus Dei), on the other hand, argues in favour of the candidate.

ADVOCAAT VAN DE DUIVEL

Soms wordt er wel eens gezegd dat iemand advocaat van de duivel speelt. Daarmee wordt bedoeld dat iemand expres de negatieve kanten van een zaak laat zien of juist de kant van de tegenstander probeert te verdedigen. Mensen spelen wel eens advocaat van de duivel om anderen te laten nadenken. Soms lijkt het heel logisch dat iemand gelijk heeft, maar als je de zaak omdraait heeft de ander misschien ook wel gelijk. Dat is niet altijd leuk om je te realiseren. Probeer zelf maar eens advocaat van de duivel te spelen als je eens ruzie met iemand hebt of het niet eens bent met iemand. Probeer dan te bedenken waarom die ander misschien toch gelijk heeft, of waarom de ander misschien ook boos op jou is.

Elke crimineel heeft recht op een advocaat. Dus de grootste boef van allemaal, de duivel, zou dan ook een advocaat moeten hebben.

Voordat in de katholieke kerk iemand door de paus heilig werd verklaard, moet er eerst in Rome een uitvoerig proces plaatsvinden. Daarbij was ook een tegenstander: de advocaat van de duivel. Die komt dan met allerlei argumenten waarom de aanstaande heilige juist niet heilig genoemd mag worden.

Waar komt de uitdrukking advocaat van de duivel spelen vandaan en wat wordt ermee bedoeld?

Wie advocaat van de duivel speelt, doet zich voor als een zwartkijker bij een overleg of discussie: hij stelt kritische vragen en maakt op- en aanmerkingen vanuit een zo negatief mogelijk standpunt. Vaak wordt dat gedaan om te kijken of alle minpunten van een plan wel goed in kaart zijn gebracht, of om een beeld te krijgen van wat er allemaal mis zou kunnen gaan.

Je kunt ook expliciet gevraagd worden om in een discussie advocaat van de duivel te spelen. Of je kunt zelf zeggen: ‘Ik speel nu even advocaat van de duivel.’ Dan verdedig je een standpunt (waar je mogelijk zelf niet eens achter staat) dat helemaal ingaat tegen het standpunt van de ander. Het is een manier om de discussie te verlevendigen of om de discussiepartners te leren argumenteren.

Met de advocaat van de duivel wordt eigenlijk de persoon bedoeld die bij zalig- en heiligverklaringen in de rooms-katholieke kerk kritische vragen stelt over de heiligheid van de kandidaat. Er wordt een soort rechtszaak opgevoerd waarin wordt nagegaan of deze kandidaat het werkelijk waard is om zalig of heilig verklaard te worden. Volgens het Groot Uitdrukkingenwoordenboek van Van Dale (2006) heeft de advocaat van de duivel (advocatus diaboli) als taak bezwaren tegen de kandidaat te opperen. De advocaat van God (advocatus Dei) voert juist een pleidooi vóór de kandidaat.

THE DEVIL’S ADVOCATE Monsignor Verde, Promotor Fidei (also known as the Avocatus Diaboli) opposes the canonisation of Jeanne d’Arc

Someone who supports an opposite argument or one that is not popular in order to make people think seriously

AMERICAN DICTIONARY The devil’s advocate

One approach takes its name from a role in Catholic Church law: the advocatus diaboli. The function of this person is to present arguments against the canonisation of someone who is being proposed for canonisation (e.g. serious character defects, or the misrepresentation of the necessary miracles – fake news, if you will).

We ourselves can take a similar critical position regarding our beliefs and claims. If our mind truly functions as a lawyer, then we are well equipped to play this contradictory role. All we have to do is mentally switch sides.

What possible reasons are there that we are wrong? Does the evidence we cite for our opinion hold up under criticism, or are we glossing over its flaws and holes? Does it exclusively support our argument, or is it also compatible with alternatives? Can we find evidence that contradicts our position?

Under this kind of cross-examination, however, our attachment to our cherished beliefs, opinions and hypotheses might start to resist fiercely, chasing us back to the comfortable position of illusion of certainty that we are right. Then we can bring in someone else to play the part. Trying to find holes in someone’s deeply held beliefs can be fun – even (or especially?) when that someone is your teenage daughter. It may not be pleasant for her at the time, but when she later tells you that she enthusiastically plays that role in discussions with her friends, your parental self-esteem will be boosted. (*)

In a debate, the first step is often to drop any assumption of insincerity or incompetence on the part of the other party. But even if we only want to test our own opinion, we may be tempted to associate counter-arguments with a particular person or group that we dislike or do not respect. This opens the door to motivated reasoning (“whoever puts forward such an argument is only after his own advantage”, or “whoever argues such a thing has no idea how complex the case is”). Instead, we can imagine that it is our best friend who brings that counter-argument, or the smartest person we know, and see it in that light.

Then, we need to scrutinise it, not with the intention of tearing it down, but to improve it: to find its weaknesses and armour it, and strengthen its advantages. We must disassociate ourselves from our feelings and seek motivation in the intellectual challenge to come up with an even better argument than our (virtual) opponent.

And then we step back into our own shoes and confront the improved version of the opposing viewpoint. If we then succeed in refuting it, our own position is definitely solid. If we cannot, then we have actually convinced ourselves that there is a better argument than ours.

When we have the devil’s advocate as our companion, we are not choosing a comfortable life. Constantly questioning our choices and looking for flaws in our logic is not a pleasant experience for those who just want to be right.

But if we don’t care about that, and on the contrary are looking for the truth, then we are in good company with the devil’s advocate. Even if we realise that this search will never end, and that we have to resign ourselves to being in a state of permanent doubt, with them at our side we become a little wiser with every step of the way.

De advocaat van de duivel

Eén benadering ontleent haar naam aan een rol in het katholieke Kerkrecht: de advocatus diaboli. De functie van deze persoon is het aanvoeren van argumenten tegen de canonisering van iemand die wordt voorgedragen om te worden heiligverklaard (bijvoorbeeld ernstige karaktergebreken, of het onjuist voorstellen van de benodigde mirakels – fake nieuws, zo u wil).

We kunnen zelf een gelijkaardige kritische positie innemen aangaande onze overtuigingen en beweringen. Als onze geest werkelijk functioneert als een advocaat, dan zijn we goed uitgerust om deze tegensprekelijke rol te spelen. Al wat we moeten doen is mentaal van kant verwisselen.

Welke mogelijke redenen zijn er dat we het verkeerd voorhebben? Houdt het bewijsmateriaal dat we aanvoeren voor onze opinie stand onder kritiek, of verdoezelen we de gebreken en de gaten erin? Ondersteunt het exclusief onze argumentatie, of is het ook compatibel met alternatieven? Kunnen we evidentie vinden die onze positie tegenspreekt?

Onder dit soort kruisverhoor zou onze gehechtheid aan onze geliefkoosde overtuigingen, opinies en hypotheses echter wel eens heftig weerwerk kunnen gaan bieden, en ons terugjagen naar de comfortabele positie van de illusie van zekerheid dat we het bij het rechte eind hebben. Dan kunnen we iemand anders inschakelen om de rol te spelen. Proberen gaten te vinden in iemands diepgewortelde overtuigingen kan best leuk zijn – zelfs (of in het bijzonder?) wanneer die iemand je tienerdochter is. Voor haar is het misschien niet zo prettig op dat moment, maar wanneer ze je later vertelt dat ze zelf met veel enthousiasme die rol speelt in discussies met haar vrienden, dan krijgt je ouderlijke zelfbeeld toch wel een flinke opkikker. (*)

In een debat is de eerste stap vaak het laten vallen van elke veronderstelling van onoprechtheid of incompetentie van de tegenpartij. Maar zelfs als we enkel onze eigen opinie willen toetsen, kunnen we in de verleiding komen tegenargumenten te associëren met een bepaalde persoon of groep, waar we een afkeer van hebben, of die we niet respecteren. Dat zet de deur open voor gemotiveerd redeneren (“wie met zo’n argument aankomt is alleen op eigen voordeel uit”, of “wie zoiets bepleit heeft geen flauw idee hoe complex de zaak wel is”). In plaats daarvan kunnen we ons inbeelden dat het onze beste vriend(in) is die dat tegenargument brengt, of de slimste mens die we kennen, en het in dat licht bekijken.

Vervolgens moeten we het onder de loep houden, niet met de bedoeling het af te kraken, maar om het te verbeteren: de zwakke punten vinden en ze pantseren, en de voordelen verstevigen. We moeten onszelf distantiëren van onze gevoelens, en motivatie zoeken in de intellectuele uitdaging met een nóg betere argumentatie voor de dag te komen dan onze (virtuele) tegenstander.

En dan stappen we weer in onze eigen schoenen, en confronteren we de verbeterde versie van het tegenovergestelde standpunt. Als we er dán in slagen het te weerleggen, dan was onze eigen positie beslist solide. Kunnen we het niet, dan hebben we eigenlijk onszelf ervan overtuigd dat er een beter argument is dan het onze.

Wanneer we de advocaat van de duivel als levensgezel hebben, dan kiezen we niet voor een comfortabel leven. Voortdurend onze keuzes in vraag stellen en speuren naar de gebreken in onze logica, daar is niks prettigs aan voor wie eigenlijk alleen maar gelijk wil.

Maar als dat ons niet kan schelen, en we integendeel op zoek zijn naar de waarheid, dan zijn we in goed gezelschap met de advocaat van de duivel. Ook al beseffen we dat die zoektocht nooit eindigt, en we onszelf erin moeten schikken in een toestand van permanente twijfel te verkeren, met hen beiden aan onze zijde worden we bij elke stap op onze reis een beetje wijzer.

Our minds are sometimes compared to lawyers: more concerned with winning our case than with uncovering the truth.

Various insights from the behavioural sciences seem to endorse this. Traits such as overconfidence, and cognitive tendencies such as confirmation bias (picking out and interpreting information so that it confirms our beliefs) and motivated reasoning (when our thinking is influenced by our motives and goals) are definitely more useful when you want to be right, rather than admitting that you are not so sure.

Indeed, we find support for our ‘rightness’ in numbers. We conform to social norms – something spectacularly illustrated in Solomon Asch’s agreement experiments, in which participants, regardless of the facts, adopted the opinions of others in the group. Moreover, we feel strengthened in our conviction when others copy our choices, be it when buying a car, selecting a holiday destination, or regularly visiting a restaurant. We love being right.

At least when it comes down to it. Even if we think chocolate ice cream is best, we have no problem accepting that others like strawberry or even vanilla ice cream better, and we feel no urge to insist that our preferred flavour is better than the rest. But for beliefs that are weightier, even if they have their origin in facts, they soon take on an emotional significance. Then we feel that our point of view is superior, perhaps even the only one that makes sense.

If we only care about being right (if only in our imagination), these tendencies are not a big problem. After all, it is irrelevant if we are happy with our car, whether because of the mark on its hood or because it is actually objectively better than other makes.

But if we care about the truth, if we want our choices to be based on facts and evidence rather than beliefs and emotions, then these selfish tendencies will not help. Fortunately, we can do something about it.

Onze geest wordt wel eens vergeleken met een advocaat: meer begaan met winnen voor onze zaak, dan met het blootleggen van de waarheid.

Verschillende inzichten uit de gedragswetenschappen lijken dit te onderschrijven. Trekken als overmoed, en cognitieve neigingen als de confirmation bias (het uitzoeken en interpreteren van informatie zodat ze onze overtuiging bevestigt) en gemotiveerd redeneren (wanneer ons denken wordt beïnvloed door onze motieven en doelen) zijn beslist nuttiger wanneer je gelijk wil halen, in plaats van toe te geven dat je eigenlijk niet zo zeker bent.

We vinden inderdaad steun voor ons ‘gelijk’ in de aantallen. We schikken ons naar sociale normen – iets wat op spectaculaire wijze wordt geïllustreerd in de overeenstemmingsexperimenten van Solomon Asch, waarin de deelnemers, ongeacht de feiten, de opinies van de anderen in de groep overnamen. Bovendien voelen we ons gesterkt in onze overtuiging wanneer anderen onze keuzes kopiëren, of dat nu bij de aankoop van een auto is, het uitzoeken van een vakantiebestemming, of het geregeld bezoeken van een restaurant. We hebben toch zo graag gelijk.

Tenminste wanneer het erop aankomt. Zelfs als we denken dat chocolade-ijs het beste is, hebben we er geen moeite mee te accepteren dat anderen meer houden van aardbeien- of zelfs vanille-ijs, en we voelen geen drang om vol te houden dat onze voorkeursmaak beter is dan de rest. Maar voor overtuigingen die gewichtiger zijn, zelfs als ze hun oorsprong vinden in feiten, die krijgen al gauw een emotionele betekenis. Dan voelen we dat ons standpunt wel superieur is, misschien zelfs het enige dat zin heeft.

Als we enkel belang hechten aan gelijk hebben (al is het maar in onze verbeelding), dan zijn deze neigingen geen groot probleem. Het doet tenslotte niet ter zake als we gelukkig zijn met onze auto, of dat nu is omwille van het merkteken op de kap, dan wel omdat hij werkelijk objectief beter is dan andere merken.

Maar als we belang hechten aan de waarheid, als we willen dat onze keuzes berusten op feiten en evidentie, eerder dan op overtuigingen en emotie, dan helpen deze zelfzuchtige neigingen niet. Gelukkig kunnen we daar wat aan doen.

The phrase “the Devil’s advocate” is actually an idiomatic expression that originated from the Roman Catholic Church. It refers to a person who deliberately presents counterarguments or challenges to a proposal, argument, or decision in order to test its validity and identify any flaws or weaknesses. Here are the key points of the proverb “the Devil’s advocate”:

Challenging assumptions: The Devil’s advocate is someone who challenges assumptions, opinions, or decisions in order to provoke critical thinking and thorough analysis. They may take a contrary position or raise objections to encourage a more comprehensive evaluation of an idea or proposal.

Testing validity: The Devil’s advocate serves as a skeptic, probing and questioning the logic, evidence, and rationale behind a proposition. By playing the role of the Devil’s advocate, one aims to identify potential weaknesses or flaws that may have been overlooked in the original argument.

Encouraging debate: The Devil’s advocate fosters healthy debate and discussion by presenting alternative viewpoints and promoting constructive dialogue. This helps to ensure that decisions are thoroughly examined from different angles and that potential risks or downsides are carefully considered.

Promoting critical thinking: The Devil’s advocate encourages critical thinking and analysis, challenging assumptions and encouraging a deeper examination of ideas or proposals. This helps to avoid biases, uncover potential blind spots, and arrive at more well-informed and robust conclusions.

Enhancing decision-making: By providing a counterbalancing perspective, the Devil’s advocate helps decision-makers to make more informed and thoughtful choices. By thoroughly scrutinizing proposals and arguments, the Devil’s advocate aids in identifying potential weaknesses or risks and facilitates more informed decision-making.

Fostering intellectual humility: The Devil’s advocate promotes intellectual humility, recognizing that not all ideas or proposals are perfect and may benefit from scrutiny and challenge. It encourages a willingness to consider diverse viewpoints and recognize that one’s own perspective may have limitations.

Respecting differing opinions: The Devil’s advocate emphasizes the importance of respecting differing opinions and encourages open-mindedness and tolerance towards alternative viewpoints. It promotes healthy debate and critical analysis without resorting to personal attacks or hostility.

In summary, the proverb “the Devil’s advocate” refers to the practice of deliberately challenging assumptions, testing the validity of proposals, and promoting critical thinking and debate. It encourages a thorough examination of ideas and decisions to ensure their robustness and validity, and fosters intellectual humility and open-mindedness.

“The Devil’s Advocate” is a novel by Morris West published in 1959, and it was also made into a movie in 1997. It tells the story of a young lawyer named Kevin, who is hired by a prestigious law firm in New York City and quickly rises through the ranks. The novel explores various themes, including morality, ambition, and the nature of evil. Here are some key points from “The Devil’s Advocate”:

Kevin’s rise to success: The novel follows Kevin, a talented and ambitious lawyer, as he joins a powerful law firm and quickly ascends the corporate ladder. He becomes a rising star in the legal profession, winning high-profile cases and gaining wealth and prestige.

Mysterious and charismatic leader: John Milton, the enigmatic and charismatic leader of the law firm, takes Kevin under his wing and becomes his mentor. Milton is known for his persuasive and manipulative skills, and he has a reputation for being ruthless and cunning. However, Kevin gradually realizes that there may be more to Milton than meets the eye.

Moral dilemmas: As Kevin’s career progresses, he is faced with a series of moral dilemmas. He must navigate complex legal and ethical issues, including defending clients he believes may be guilty and making compromises that challenge his personal values. Kevin struggles with the tension between his ambition and his conscience, as he grapples with the moral implications of his actions.

Supernatural elements: “The Devil’s Advocate” introduces supernatural elements into the story. As Kevin delves deeper into the mysteries of the law firm and Milton’s true nature, he uncovers dark secrets and encounters supernatural forces that challenge his perceptions of reality.

Exploration of good vs. evil: The novel delves into the nature of good and evil, and the lines between them blur as Kevin wrestles with the choices he must make. The novel raises philosophical questions about the nature of morality, the existence of evil, and the choices individuals make when faced with moral dilemmas.

Psychological and emotional struggles: Kevin undergoes psychological and emotional struggles as he grapples with the choices he makes, the consequences of his actions, and the revelations he uncovers. The novel delves into Kevin’s internal conflicts and emotional turmoil as he tries to reconcile his ambition with his sense of right and wrong.

Climactic ending: “The Devil’s Advocate” builds towards a climactic ending as Kevin confronts the truth about Milton and the true nature of the law firm. The novel’s conclusion is thought-provoking and raises questions about the nature of morality, human nature, and the consequences of one’s choices.

Overall, “The Devil’s Advocate” is a thought-provoking novel that explores complex themes and raises philosophical questions about morality, ambition, and the nature of evil. It delves into the psychological and emotional struggles of its protagonist as he navigates the dark and mysterious world of the legal profession.

Exploding iPhone Prank

18 dec. 2012