Fairness is what justice really is

Page Description

It challenges traditional notions,

exploring moral decision-making complexities,

contradictions, emotions,

and social factors’ influence.

Law is derived from logic and experience.

It has rules to govern its application, penalties for its violation, and remedies for those aggrieved.

Yet it tends to be slow, unpredictable, unnecessarily complicated at times, and selectively enforced at others.

And then there are the paradoxes that make law even more enigmatic.

Recht is gebaseerd op logica en ervaring.

Het heeft regels om de toepassing ervan te regelen, straffen voor overtreding en oplossingen voor degenen die onrecht is aangedaan.

Toch is het vaak traag, onvoorspelbaar, soms onnodig ingewikkeld en op andere momenten selectief gehandhaafd.

En dan zijn er de paradoxen die het recht nog raadselachtiger maken.

When Justice Goes Astray: A System’s Hidden Contradictions

Justice, in its ideal form, is the pursuit of fairness, truth, and accountability. Yet, history and human experience reveal a profound paradox: the very systems designed to uphold justice can sometimes perpetuate its opposite – inequity, harm, and oppression. This page explores the intricate tension between law and morality, between fairness and power, and between what is just and what is legal. Through thought-provoking examples and critical insights, “The Justice Paradox” invites you to reflect on the complexities of justice and the moral dilemmas that arise when its pursuit falls short of its promise, ultimately undermining its own goals.

Wanneer Gerechtighid Dwaalt: Verborgen Tegenstellingen in het Systeem

Gerechtigheid, in haar ideale vorm, is het nastreven van eerlijkheid, waarheid en verantwoordelijkheid. Toch onthullen geschiedenis en menselijke ervaring een diepgaande paradox: de systemen die ontworpen zijn om gerechtigheid te waarborgen, kunnen soms juist het tegenovergestelde bevorderen – ongelijkheid, schade en onderdrukking. Deze pagina verkent de ingewikkelde spanning tussen wet en moraal, tussen eerlijkheid en macht, en tussen wat rechtvaardig is en wat legaal is. Aan de hand van prikkelende voorbeelden en kritische inzichten nodigt ‘Het Rechtvaardigheidsparadox’ je uit om na te denken over de complexiteit van gerechtigheid en de morele dilemma’s die ontstaan wanneer rechtvaardigheid in haar belofte tekortschiet en daardoor haar eigen doelen ondermijnt.”

This translation retains the philosophical and reflective tone, with a focus on the paradox of justice failing to live up to its promise. It now reads more smoothly in Dutch while preserving the original intent.

1 When entities within justice make a mistake

- When a picture is painted on paper that is simply not possible in reality;

- justice derails;

- justice enters the danger zone;

- toxic improper use arises;

- unimaginable perverse abuse;

- dysfunctions – an abhorrent improper event that strikes a person to their core from out of nowhere;

- structural dysfunctions in justice are a contradiction in terms…

Wanneer entiteiten binnen justitie zich vergissen

- Wanneer op papier een beeld ontstaat die in

- werkelijkheid domweg niet mogelijk is;

- justitie ontspoort;

- justitie komt in de gevarenzone;

- er ontstaat toxisch oneigenlijk gebruik;

- zich niet voor te stellen pervers misbruik;

- disfuncties – een abject oneigenlijk gebeuren, die een mens vanuit het niets overkomt – raakt de diepste vezels van zijn bestaan;

- structurele disfuncties bij justitie zijn een contradictio in terminis …

Sometimes justice doesn’t amount to much, for example, ‘The blind leading the blind’. Someone can effortlessly undermine and disrupt justice, turning it into a dead end street!

Soms stelt justitie niet veel voor, voorbeeld ‘The blind leading the blind’. Moeiteloos kan iemand justitie ondermijnen en ontwrichten en wordt het een sukkelstraatje!

Deceiving justice with established tangible absurdities is surreal. This tends towards fraudulent justice, doesn’t it?

That someone can convince justice of the most absurd lies goes against common sense.

The kind of justice that gets caught up in this is meaningless.

Justitie om de tuin leiden met vaststaande tastbare ongerijmdheden is surreëel. Zoiets neigt naar frauduleuze justitie? Dat iemand justitie de ongerijmdste leugens kan wijsmaken is in strijd met het gezond verstand. Het soort justitie die daarin verstrikt geraakt is zonder betekenis.

2 It seems like a philosophical statement

- There is a paradox in justice.

- Justice deals with things that do not exist.

- Justice is opposed to what is inherently part of life.

- Justice is opposite to the law of nature.

- Justice versus conscience (the title of the website).

- The essence disappears: a foundation of ordinary honesty.

- There is a gap where justice becomes a substitute for abject consciencelessness!

Er bestaat een justitie paradox

- Justitie houdt zich bezig met dingen die er niet zijn.

- Justitie tegengesteld aan wat immanent deel uitmaakt van het leven.

- Justice opposite to the law of nature.

- Justitie versus het geweten (de titel van de website).

- De essentie verdwijnt: een basis aan doodgewone eerlijkheid.

- Er is een leemte waar justitie een substituut is van abjecte gewetenloosheid!

Lady Justice represents fairness:

she is carrying scales that represent balance in all things.

she is blindfolded in order to be fair to EVERYONE.

she has a sword to defend everyone’s rights.

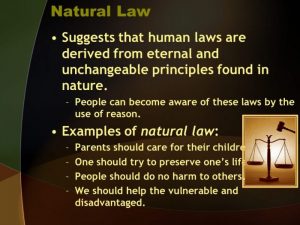

3 Key Principles of Natural Law Theory

Some key points associated with natural law theory are:

- It assumes that there is an objective, natural order to the universe that can be discovered through reason and observation.

- It suggests that certain actions are inherently right or wrong based on their conformity to this natural order.

- It often emphasizes the importance of individual rights and freedoms as a reflection of the natural order of things.

Hoofdprincipes van de Natuurwet

Enkele kernpunten die verbonden zijn met de theorie van de natuurwet zijn:

- Het gaat ervan uit dat er een objectieve, natuurlijke orde in het universum is die door middel van rede en observatie kan worden ontdekt.

- Het suggereert dat bepaalde handelingen inherent goed of slecht zijn, afhankelijk van hun overeenstemming met deze natuurlijke orde.

- Het benadrukt vaak het belang van individuele rechten en vrijheden als een weerspiegeling van de natuurlijke orde der dingen.

Justice does things that are completely absurd.

It is something to worry about.

It is why this website is under construction.

An endless string of people in pain and horror behind bars,

because justice is not working.

Even children, like The Central Five,

just 14 years old, innocent in prison.

It was abhorrent and it shouldn’t have happened.

Even on the electric chair,

like George Stinney, a boy only 14.

Such a thing is incomprehensible.

Een paradox is een uitspraak die niet overeenstemt met de gangbare mening.

A paradox is a statement that disagrees with common opinion.

A statement that seems to contradict itself, but reveals a deeper truth through its contradiction.

Examples:

Where there is no law, there is no freedom (John Locke)

Cowards die many times before their deaths (Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar)

Paradox

a situation or statement that seems impossible or is difficult to understand because it contains two opposite facts or characteristics

a statement or situation that may be true but seems impossible or difficult to understand because it contains two opposite facts or characteristics

Cambridge Dictionary

A paradox is a statement or situation that appears to be self-contradictory or absurd but may, in fact, be true. The key points of a paradox include:

Contradiction: A paradox involves a contradiction or a conflict between two or more ideas, concepts, or statements.

Apparent truth: A paradox often appears to be true or logical, despite the contradiction it contains.

Surprise: A paradox can be surprising or unexpected, as it challenges our assumptions or common sense.

Irony: Paradoxes can be ironic because they often involve a reversal of expectations or outcomes.

Resolving the contradiction: A paradox can be resolved by finding a deeper truth or a different perspective that reconciles the apparent contradiction.

Philosophical value: Paradoxes often have philosophical significance, as they can shed light on fundamental questions about reality, knowledge, and human nature.

Overall, a paradox can be a powerful tool for exploring complex ideas, challenging assumptions, and deepening our understanding of the world around us.

“The Justice Paradox” is a book written by Joshua Greene, a philosopher and cognitive scientist, that explores the challenges and complexities of moral decision-making and justice from a cognitive and psychological perspective. Some key points of “The Justice Paradox” include:

Dual Process Theory: Greene proposes that moral decision-making involves two cognitive processes – a fast, automatic, emotional process (referred to as “Type 1”) and a slow, deliberative, reasoning process (referred to as “Type 2”). He argues that these two processes often conflict with each other, leading to moral dilemmas and paradoxes.

Moral Dilemmas: Greene uses moral dilemmas, such as the famous trolley problem, to illustrate how our moral intuitions can vary depending on the framing of the situation and the emotional responses triggered by different scenarios. He suggests that our intuitions are often guided by emotional reactions, rather than logical reasoning.

Moral Tribalism: Greene discusses how moral decision-making is often influenced by social and tribal factors, such as group identity, political affiliation, and cultural norms. He argues that our moral judgments are often biased and shaped by our social context, leading to conflicts and contradictions in our sense of justice.

Utilitarianism vs. Deontology: Greene explores the tension between utilitarianism, which emphasizes the greatest good for the greatest number of people, and deontology, which emphasizes moral rules and duties regardless of the consequences. He suggests that these two moral frameworks often clash, creating moral dilemmas and paradoxes.

Neuroscience and Moral Decision-making: Greene draws on insights from neuroscience to understand how the brain processes moral information and how emotions, intuitions, and reasoning interact in moral decision-making. He argues that understanding the neural mechanisms underlying moral judgments can shed light on the nature of justice and moral paradoxes.

Practical Implications: Greene discusses the implications of his research for practical issues such as criminal justice, political decision-making, and moral education. He suggests that a deeper understanding of the cognitive and psychological processes underlying moral decision-making can inform policy and help us navigate the complexities of justice in a more nuanced and informed way.

Overall, “The Justice Paradox” challenges traditional notions of justice and morality, and explores the complexities and contradictions inherent in our moral decision-making processes, shedding light on the interplay between emotions, intuitions, reasoning, and social factors in shaping our sense of justice.

1 Fouten bij justitie, wie controleert het Openbaar Ministerie?

11 nov. 2019

SHOCKING CONTENT

2 Wrongly Imprisoned: How Fair is Uk Justice

Robert Brown face 25 years imprisoned for a crime he didn’t commit, framed by crooked cops and left to rot – but he never gave up. He was released after 25 years after his conviction was deemed unsafe and him innocent – a changed man with a quarter of a century lost.

The Dark Side of UK Justice – Miscarriage of Justice

12 jun. 2020

.

Article De Standaard 21 May 2016 pdf and link to De Standaard see lower

4 Who thinks too much about the impact of rulings written too quickly, goes crazy’.

Are we still a constitutional state worthy of the name?

What is really going on behind the scenes of Belgian justice? We went in search of the answer to a fundamental question: can judges still rule properly in this country? Are we still a constitutional state worthy of the name? The answer is appalling: no.

In the busy sections of our courts of first instance, it is bubbling over. Take the juvenile court in Antwerp, where each juvenile court judge looks after an average of 450 children and young people. Too many to be good’, says youth judge Philippe Vandaele. It tends towards assembly-line work, it is said in many courts.

Mistakes

The bar is inevitably lowered. The quality of judgments is declining, judges admit – although no one wants to go so far as to say that they no longer trust their own judgments. Sometimes I think: this could have been done better’, says a promising judge from Ghent. You make decisions that have a great impact on people’s lives. If you dwell on that too much, you go crazy.’

Mistakes are made. Many more than allowed, …

Artikel De Standaard 21 mei 2016 pdf en link naar De Standaard zie lager

‘Wie te veel nadenkt over de impact van te snel geschreven vonnissen, wordt gek’

Zijn we nog een rechtsstaat die naam waardig?

Wat gaat er werkelijk om achter de schermen van de Belgische justitie? We gingen op zoek naar het antwoord op een fundamentele vraag: kunnen rechters nog naar behoren rechtspreken in dit land? Zijn we nog een rechtsstaat die naam waardig? Het antwoord is ontstellend: neen.

Op de drukke secties van onze rechtbanken van eerste aanleg is het hozen. Neem de jeugdrechtbank in Antwerpen, waar elke jeugdrechter gemiddeld 450 kinderen en jongeren opvolgt. ‘Te veel om goed te zijn’, zegt jeugdrechter Philippe Vandaele. Het neigt naar bandwerk, klinkt het op veel rechtbanken.

Fouten

De lat gaat onvermijdelijk lager. De kwaliteit van de vonnissen neemt af, geven rechters toe – al wil niemand zo ver gaan om te zeggen dat ze hun eigen uitspraken niet meer vertrouwen. ‘Soms denk ik: dit had misschien beter gekund’, zegt een beloftevolle Gentse rechter. ‘Je neemt beslissingen met een grote impact op het leven van mensen. Als je daar te veel bij stilstaat, word je gek.’

Er worden fouten gemaakt. Veel meer dan toegelaten, …

3 Japan: Guilty Until Proven Innocent | 101 East

6 okt. 2016

4 How Bad Lawyers Get Rich Off People in Houston Jails

15 feb. 2021

5 Peter’s journey through our broken criminal justice system

29 jan. 2019

M.a.w. dit is de justitie paradox vernoemd in punt 2

The word “justice” often evokes deep emotions, especially in contexts where injustices have occurred and the truth needs to be uncovered. It can refer to legal justice, ethical principles, or a sense of moral restoration. In what context would you like to discuss “justice”? For example, is it about legal matters, personal experiences, or societal issues such as the Post Office scandal?

Het woord “gerechtigheid” roept vaak diepe emoties op, vooral in contexten waar onrecht is aangedaan en de waarheid aan het licht moet komen. Het kan verwijzen naar juridische rechtvaardigheid, ethische principes, of een gevoel van moreel herstel. In welke context wil je over “gerechtigheid” praten? Bijvoorbeeld, gaat het over juridische zaken, persoonlijke ervaringen, of maatschappelijke kwesties zoals het Post Office-schandaal?

The distinction between “rechtvaardigheid” and “gerechtigheid” in Dutch can be nuanced, especially when discussing abstract concepts like justice. Here’s a deeper explanation of the philosophical dimension in “gerechtigheid”:

Rechtvaardigheid: This term generally refers to fairness or equity in practical terms. It deals with how actions, decisions, or systems conform to moral or ethical standards of fairness. It’s often used in everyday contexts, focusing on the application of justice—e.g., laws being applied fairly or treating people equally.

Gerechtigheid: This term has a broader, often philosophical or idealistic dimension, encompassing the concept of ultimate or absolute justice. It often goes beyond practical fairness to include moral, ethical, and even spiritual ideals. “Gerechtigheid” can involve questions like:

- What is truly right or just in the grand scheme of things?

- How does justice align with concepts like truth, morality, or divine will?

- Is there a higher, universal standard of justice that transcends human-made laws?

In philosophical discussions, “gerechtigheid” might explore the ideal state of justice, as envisioned by thinkers like Plato, Aristotle, or Kant, who pondered the relationship between laws, morality, and the ultimate good. For example, Plato’s idea of “justice” in his work The Republic is more about the harmony and balance of the whole society, which aligns more with “gerechtigheid.”

In Summary:

- “Rechtvaardigheid”: Practical fairness, ethical actions, or equity in daily life.

- “Gerechtigheid”: Ideal, abstract justice with philosophical or even metaphysical implications—often exploring deeper truths about what is fundamentally “right.”

In English, the single term “justice” is used to encompass both the practical and philosophical dimensions. However, in Dutch, the distinction between “rechtvaardigheid” and “gerechtigheid” allows for more nuance:

-

Rechtvaardigheid: Focuses on practical fairness and the ethical application of justice, often in the context of laws, rules, or interpersonal actions.

-

Gerechtigheid: Carries a deeper, philosophical or idealistic meaning, referring to a higher sense of justice that transcends human systems – something closer to universal or absolute justice.

This linguistic distinction enables Dutch speakers to articulate different aspects of justice more precisely, depending on the context. English speakers, in contrast, rely on context, modifiers, or additional explanations (e.g., “social justice,” “poetic justice,” or “ultimate justice”) to convey similar nuances.

This difference highlights how languages shape the way we think and communicate about complex ideas like justice. Would you like examples of how these words are used in sentences to illustrate this further?

The opening text reflects on justice as an ideal – a concept that embodies fairness, truth, and accountability, but also explores the broader philosophical paradoxes and moral dilemmas. This aligns more with the philosophical and abstract dimension of “gerechtigheid”, rather than the practical fairness implied by “rechtvaardigheid”.

6 Granny Catapulted In The Garbage