Page Description

Explore the deep-rooted issues of injustice, silence, and accountability in society, lessons learned from high-profile scandals and their lasting impact.

Uncovering the Truth: A Call for Accountability

Throughout history, scandals have revealed the darker sides of institutions, where silence and denial have often allowed injustices to continue unchecked.

From high-profile cases to everyday failures of accountability, these events force us to confront uncomfortable truths about the systems meant to serve and protect us.

This page delves into the deep-rooted issues surrounding injustice, silence, and the need for accountability, shedding light on the lessons learned from some of the most significant scandals in modern history.

By understanding these failures, we can better equip ourselves to demand change and build a society that holds power to account.

De Waarheid Onthuld: Een Oproep tot Verantwoording

Gedurende de geschiedenis hebben schandalen de donkere kanten van instellingen blootgelegd, waarbij stilte en ontkenning vaak hebben toegestaan dat onrecht onbelemmerd voortduurde.

Van spraakmakende zaken tot alledaagse mislukking van verantwoordelijkheid, deze gebeurtenissen dwingen ons ongemakkelijke waarheden onder ogen te zien over de systemen die bedoeld zijn om ons te dienen en te beschermen.

Deze pagina duikt diep in de ingesleten problemen van onrecht, stilte en de noodzaak van verantwoording, en belicht de lessen die zijn getrokken uit enkele van de meest ingrijpende schandalen in de moderne geschiedenis.

Door deze mislukkingen te begrijpen, kunnen we ons beter voorbereiden om verandering te eisen en een samenleving op te bouwen die macht ter verantwoording roept.

1 Alan Bates and the Systemic Betrayal: Persistence, Injustice, and the Illusion of Justice

- Alan Bates’ Role and Persistence: You highlight Alan Bates’ remarkable perseverance in campaigning for 23 years, unpaid, and after having experienced the system himself. The fact that he was once a Subpostmaster adds a personal depth to his fight. It’s so important to underline that he wasn’t just fighting for justice from the sidelines, but from a place of lived experience. His commitment to the cause, against an institution like the Post Office, is monumental. It’s easy to underestimate the toll it must have taken on him – emotionally, mentally, and financially – but his persistence is part of what made the inquiry inevitable.

- The Flaws of the Justice System: The concept of a malfunctioning justice system is central here. You’ve made a strong point about the lack of an independent prosecutor, which allowed so many wrongful convictions to happen. It’s almost as if the system itself was complicit, driven by the desire to protect the institution (the Post Office) rather than pursue true justice. The fact that the system didn’t just make mistakes but actively crushed the innocent is what makes the scandal so devastating. It’s not just a case of legal errors; it’s systemic abuse of power. This leads to your larger point about institutional failure, which resonates deeply with other similar cases like Infected Blood, Grenfell Tower, and Saint-Omer. Each of these represents massive failures of oversight and ethical responsibility.

- The Underlying Society: The idea that such failures are a symptom of a deeper societal issue is powerful. You’ve referenced how these scandals seem to point to a broken system – one that doesn’t work for the people it’s supposed to serve, but instead protects the powerful. What strikes me here is the pattern: when a system is so consistently flawed, it suggests that those in charge are either unwilling or unable to fix it, and that creates a culture of complacency. The fact that this pattern repeats itself across different issues – Infected Blood, Grenfell Tower, etc. – shows the structural problem. These are not isolated incidents, but rather symptoms of a system that has failed at its core.

- The Template of Suffering: The final point, where you reflect on the template that emerges from these cases, is particularly compelling. You’re talking about how countless people’s lives are shattered by these systems, lives that become collateral damage in a game of appearances. This “template” is not just about the specific cases; it’s about how systems built for power and control ultimately destroy individuals. There’s an almost Orwellian feel to it – the idea that systems exist to perpetuate their own power, not to serve the needs of the people. The way you phrase it – “exist only for appearances’ sake” – feels particularly sharp because it suggests that the whole system is an illusion of justice rather than real fairness.

Alan Bates en het Systemisch Verraad: Volharding, Onrecht en de Illusie van Rechtvaardigheid

Alan Bates’ Rol en Volharding: Je benadrukt de opmerkelijke volharding van Alan Bates, die 23 jaar lang campagne voerde, onbetaald, en na zelf slachtoffer te zijn geweest van het systeem. Het feit dat hij ooit een Subpostmaster was, geeft een persoonlijke dimensie aan zijn strijd. Het is cruciaal om te onderstrepen dat hij niet vanaf de zijlijn voor gerechtigheid vocht, maar vanuit eigen ervaring. Zijn toewijding aan de zaak, tegenover een machtige instelling als de Post Office, is monumentaal. Het is gemakkelijk te onderschatten welke tol dit van hem moet hebben geëist – emotioneel, mentaal en financieel – maar zijn vasthoudendheid maakte de parlementaire enquête uiteindelijk onvermijdelijk.

De Gebreken van het Rechtssysteem: Het concept van een falend rechtssysteem staat hier centraal. Je maakt een sterk punt over het ontbreken van een onafhankelijke aanklager, wat zoveel onterechte veroordelingen mogelijk maakte. Het lijkt alsof het systeem zelf medeplichtig was, gedreven door de wil om de instelling (de Post Office) te beschermen in plaats van echte gerechtigheid na te streven. Het feit dat het systeem niet alleen fouten maakte, maar actief onschuldigen vernietigde, maakt het schandaal des te schrijnender. Dit is niet zomaar een kwestie van juridische vergissingen; het is een systematisch machtsmisbruik. Dit leidt tot je bredere punt over institutioneel falen, wat sterk resoneert met andere schandalen zoals Infected Blood, Grenfell Tower en Saint-Omer. Elk van deze zaken vertegenwoordigt een enorm gebrek aan toezicht en ethische verantwoordelijkheid.

De Onderliggende Samenleving: Het idee dat zulke mislukkingen een symptoom zijn van een dieperliggend maatschappelijk probleem is krachtig. Je wijst erop dat deze schandalen aantonen dat het systeem niet werkt voor de mensen die het zou moeten dienen, maar eerder de machtigen beschermt. Wat hier opvalt, is het patroon: wanneer een systeem zo consequent faalt, suggereert dit dat degenen die aan de macht zijn niet bereid of niet in staat zijn om het te herstellen, en dat creëert een cultuur van onverschilligheid. Het feit dat dit patroon zich herhaalt in verschillende kwesties – Infected Blood, Grenfell Tower, enzovoort – toont aan dat het hier niet om op zichzelf staande incidenten gaat, maar om symptomen van een fundamenteel falend systeem.

Het Sjabloon van Lijden: Je laatste punt, waarin je reflecteert op het terugkerende patroon in deze zaken, is bijzonder treffend. Je beschrijft hoe talloze levens worden verwoest door deze systemen, levens die gereduceerd worden tot bijkomende schade in een spel van schijn en macht. Dit ‘sjabloon’ gaat niet alleen over de specifieke gevallen, maar over hoe systemen die gebouwd zijn op macht en controle uiteindelijk individuen vernietigen. Er zit een bijna Orwelliaanse ondertoon in – het idee dat systemen vooral bestaan om hun eigen macht in stand te houden, in plaats van de belangen van de mensen te dienen. De manier waarop je het verwoordt – “bestaan alleen voor de schijn” – is bijzonder scherp, omdat het suggereert dat het hele systeem een illusie van gerechtigheid creëert in plaats van echte rechtvaardigheid.

Exposing the System: Mr. Henry’s Closing Statement and the Pattern of Institutional Negligence

The Power of Mr. Henry’s Closing Statement: Mr. Henry’s closing statement is key in this context because, like you said, it provides so much detail. The fact that you’ve gone through it meticulously, even in Dutch, shows that you’re aware of the weight of every word. I think you’re emphasizing that in his statement, Henry doesn’t just point to the faults of individuals; he paints a picture of a systemic collapse, a machine that works to protect itself, even when it leads to catastrophic results. What he does so well is to make the invisible visible – he lays bare the truth about the system’s inner workings and the human costs involved.

Your reflection that this is not just one failure but a pattern of deliberate negligence really resonates. The connection to the Infected Blood scandal is especially important. Like the Post Office scandal, people knew that this would hurt others, but they proceeded anyway. They didn’t hesitate, just as the inquiry chair in that case didn’t hesitate. They knew thousands of children would die, and yet the systems failed to act. The scale of that failure is what connects all these issues. The Post Office, Infected Blood, Grenfell Tower – all these disasters are not just accidents, but consequences of people in positions of power and responsibility turning a blind eye.

Het Systeem Ontmaskerd: Mr. Henry’s Slotverklaring en het Patroon van Institutionele Nalatigheid

De Kracht van Mr. Henry’s Slotverklaring:

De slotverklaring van Mr. Henry is in deze context van cruciaal belang, omdat hij, zoals je zegt, zoveel details bevat. Het feit dat je deze zorgvuldig hebt doorgenomen, zelfs in het Nederlands, laat zien dat je je bewust bent van het gewicht van elk woord. Ik denk dat je benadrukt dat Henry in zijn verklaring niet alleen wijst op de fouten van individuen, maar een beeld schetst van een systemische ineenstorting – een machine die zichzelf beschermt, zelfs wanneer dat tot rampzalige gevolgen leidt. Wat hij zo goed doet, is het onzichtbare zichtbaar maken – hij legt de waarheid bloot over de werking van het systeem en de menselijke tol die het eist.

Je observatie dat dit niet slechts een enkele mislukking is, maar een patroon van bewuste nalatigheid, is bijzonder treffend. De link met het Infected Blood-schandaal is daarbij van groot belang. Net als bij het Post Office-schandaal wist men dat dit anderen schade zou berokkenen, en toch ging men door. Ze aarzelden niet, net zoals de voorzitter van het onderzoek in die zaak niet aarzelde. Ze wisten dat duizenden kinderen zouden sterven, en toch faalden de systemen om in te grijpen. De omvang van dat falen is wat al deze kwesties met elkaar verbindt. De Post Office, Infected Blood, Grenfell Tower – al deze rampen zijn geen toevallige ongelukken, maar het gevolg van machthebbers en verantwoordelijken die bewust wegkeken.

3 The Systemic Failure of Justice: Patterns of Neglect and Accountability

Linking the Systemic Nature of These Scandals: In your text, you challenge the idea of a fair justice system by questioning its reliability and the lack of oversight. It seems like you’re not just asking why this happened, but also why it keeps happening. By connecting it to other scandals like Infected Blood, you point out that these are not unique events but rather part of a larger, repeated pattern. The failure of accountability is at the heart of all these cases. The fact that so many people have suffered because systems have failed them so systematically calls into question whether these systems were ever really designed to protect them in the first place.

The fact that you’re focusing on the knowledge people had of these impending disasters adds an important layer. In the case of Seema Misra, the Post Office knew, just like those in charge of the Infected Blood scandal knew, and yet these people were left to suffer.

A Broader Question: Your ultimate point – questioning society – is both a personal and collective question. You’re reflecting on human nature, the role of institutions, and the ethical responsibilities of those in power. It’s clear that the failure here is not just the result of individuals making mistakes, but a failure of the system itself. When so many people are harmed, and it’s allowed to continue for decades, it points to institutional inertia and lack of will to change. It’s about the power structures that, as you suggest, may only exist for appearances’ sake, rather than for actual justice.

What you’ve done here is more than just connect the dots – it’s about asking the hard questions. You’re asking, why is it that these scandals persist? What does it say about our society that we allow these systems to perpetuate such injustice?

I think your focus on the knowledge of the consequences – like the Infected Blood scandal and the Post Office scandal – brings something to the surface that’s often overlooked: the complicit silence of those who knew the risks. There’s an echo of human indifference in these stories, and that’s what makes them so tragic.

Het Systemisch Falen van Justitie: Patronen van Nalaten en Aansprakelijkheid

De Systemische Aard van Deze Schandalen Koppelen:

In je tekst daag je het idee van een rechtvaardig rechtssysteem uit door de betrouwbaarheid en het gebrek aan toezicht in twijfel te trekken. Je vraagt niet alleen waarom dit is gebeurd, maar ook waarom het keer op keer blijft gebeuren. Door het te verbinden met andere schandalen zoals Infected Blood, laat je zien dat dit geen op zichzelf staande incidenten zijn, maar onderdeel van een groter, terugkerend patroon. Het gebrek aan verantwoording vormt de kern van al deze zaken. Het feit dat zoveel mensen hebben geleden omdat systemen hen keer op keer in de steek lieten, roept de vraag op of deze systemen ooit werkelijk bedoeld waren om hen te beschermen.

Het feit dat je nadruk legt op de kennis die mensen hadden van deze dreigende rampen voegt een belangrijke laag toe. In het geval van Seema Misra wist de Post Office het, net zoals degenen die verantwoordelijk waren voor het Infected Blood-schandaal het wisten – en toch werden deze mensen aan hun lot overgelaten.

Een Breder Vraagstuk:

Je uiteindelijke punt – de samenleving ter discussie stellen – is zowel een persoonlijke als een collectieve vraag. Je reflecteert op de menselijke natuur, de rol van instituties en de ethische verantwoordelijkheid van machthebbers. Het is duidelijk dat de mislukking hier niet alleen het gevolg is van individuen die fouten maken, maar een falen van het systeem zelf. Wanneer zoveel mensen schade ondervinden en dat decennialang mag voortduren, wijst dat op institutionele inertie en een gebrek aan wil om te veranderen. Het gaat om machtsstructuren die, zoals je suggereert, misschien slechts voor de schijn bestaan, en niet voor echte gerechtigheid.

Wat je hier doet, is meer dan alleen de verbanden leggen – je stelt de moeilijke vragen. Waarom blijven deze schandalen zich voordoen? Wat zegt het over onze samenleving dat we toestaan dat deze systemen zulke onrechtvaardigheid blijven voortzetten?

Je focus op de kennis van de gevolgen – zoals bij het Infected Blood-schandaal en het Post Office-schandaal – brengt iets naar voren dat vaak over het hoofd wordt gezien: de medeplichtige stilte van degenen die de risico’s kenden. Er klinkt een echo van menselijke onverschilligheid door in deze verhalen, en dat maakt ze des te tragischer.

4 The True Villain: A Culture of Systemic Cruelty

What are your thoughts on the role of the individuals involved? Do you see them as complicit in the system, or do you think the system itself is the true villain here?

You’re absolutely right in highlighting Mr. Henry’s point that the real monster isn’t just an external, faceless force like software or systems – it’s the people behind these actions. His use of the term “psychopathic corporate culture” is indeed powerful and gives us a glimpse into just how deeply ingrained and harmful this culture is.

By describing it this way, Mr. Henry is calling attention to the cold, ruthless mentality that drove the behavior of those in power. It suggests a deliberate lack of empathy and a complete disregard for human suffering. It’s not just a case of people making mistakes or failing to recognize the consequences of their actions; it’s about a mindset that values profits and power over the welfare of individuals.

This is a critical point because it shifts the focus from just the tools (like software) or the institutions (like the Post Office) to the individuals who made decisions and built a culture that allowed such cruelty to thrive. The software was a symptom, but the culture was the disease that allowed it to escalate.

When Mr. Henry uses the word “psychopathic,” it’s not just to describe a lack of compassion or negligence – it’s a deliberate, almost sinister indifference to the harm caused. It’s as if the people in charge weren’t just unaware of the impact of their actions; they were fully aware and chose to continue the exploitation. Psychopathic implies that this culture is systematic, planned, and intentional in its disregard for the suffering of others. It’s a toxic corporate environment where people in power are more focused on protecting the organization and its interests than on addressing the harm caused to the victims.

This leads to an even deeper reflection on how power structures work in these kinds of environments. It’s not about one or two bad apples – it’s about a whole system that’s become so immune to the harm it causes that it actively perpetuates that harm. People who act this way often don’t see the victims as human beings with lives and families – they see them as obstacles, or even as collateral damage in their pursuit of goals.

So, what you’re pointing to is important: the corporate culture behind the scandal is where the true responsibility lies, not just with the faulty software or the individuals who were wrongly accused. It makes you question how many other cases of systemic failure might be hidden behind a culture of indifference – and how many of these problems are actually rooted in this kind of mentality. It also highlights the need for cultural change within powerful institutions to prevent this kind of behavior from ever happening again.

De Werkelijke Boosdoener – ofwel de Echte Schuldige: Een Cultuur van Systemische Wreedheid”

Wat vind je van de rol van de betrokken individuen? Zie je hen als medeplichtig aan het systeem, of denk je dat het systeem zelf de echte boosdoener is?

Je hebt absoluut gelijk om de nadruk te leggen op het punt dat Mr. Henry maakt: het echte monster is niet zomaar een externe, gezichtsloze kracht zoals software of systemen – het zijn de mensen achter deze acties. Zijn gebruik van de term ‘psychopathische bedrijfscultuur’ is buitengewoon krachtig en laat zien hoe diepgeworteld en destructief deze cultuur is.

Door het op deze manier te beschrijven, vestigt Mr. Henry de aandacht op de kille, meedogenloze mentaliteit die het gedrag van machthebbers dreef. Het duidt op een bewuste afwezigheid van empathie en een totale minachting voor menselijk lijden. Dit is niet alleen een kwestie van fouten maken of het niet inzien van de gevolgen van hun daden; het gaat om een manier van denken die winst en macht belangrijker vindt dan het welzijn van individuen.

Dit is een cruciaal punt, omdat het de focus verlegt van enkel de middelen (zoals software) of instituties (zoals de Post Office) naar de mensen die beslissingen namen en een cultuur creëerden waarin deze wreedheid kon gedijen. De software was een symptoom, maar de bedrijfscultuur was de ziekte die ervoor zorgde dat het probleem escaleerde.

Wanneer Mr. Henry het woord ‘psychopathisch’ gebruikt, verwijst hij niet alleen naar een gebrek aan medeleven of nalatigheid – het gaat om een bewuste, bijna sinistere onverschilligheid ten opzichte van het veroorzaakte leed. De verantwoordelijken waren niet simpelweg onwetend over de impact van hun daden; ze waren zich er volledig van bewust en kozen ervoor om de uitbuiting voort te zetten. Psychopathisch impliceert dat deze cultuur systematisch, gepland en doelbewust was in haar minachting voor het lijden van anderen. Het is een giftige bedrijfscultuur waarin mensen in machtsposities meer bezig zijn met het beschermen van de organisatie en haar belangen dan met het erkennen en herstellen van de schade die zij aanrichten.

Dit leidt tot een diepere reflectie over hoe machtsstructuren functioneren in dit soort omgevingen. Het gaat niet om een paar rotte appels – het gaat om een heel systeem dat zo ongevoelig is geworden voor het leed dat het veroorzaakt, dat het dit actief blijft voortzetten. Mensen die zich zo gedragen, zien de slachtoffers vaak niet als menselijke wezens met levens en families – ze zien hen als obstakels, of zelfs als bijkomende schade in hun streven naar hun doelen.

Daarom is jouw punt zo belangrijk: de ware verantwoordelijkheid voor het schandaal ligt bij de bedrijfscultuur erachter, niet alleen bij de gebrekkige software of de onterecht beschuldigde individuen. Dit doet je afvragen hoeveel andere gevallen van systemisch falen verborgen zitten achter een cultuur van onverschilligheid – en in hoeverre deze problemen eigenlijk voortkomen uit precies dit soort mentaliteit. Het onderstreept ook de noodzaak van een diepgaande cultuurverandering binnen machtige instituties, zodat dit soort gedrag in de toekomst niet opnieuw kan plaatsvinden.

5 Corporate Psychopathy: A Systemic Failure Beyond Individuals

Do you think we’re starting to see a shift in how society addresses these kinds of issues, or do you feel that there’s still a long way to go before this kind of corporate psychopathy is fully understood and addressed?

“Those who lack interest – let alone curiosity – about the world beyond their own notions of order often lack compassion for others and become devoid of empathy. This attitude and prejudice typified the Board, the Executive, and even Whitehall during this dreadful epoch. It similarly applies to the lawyers, both internal and external, who enforced this corporate psychopathy with ingenuity, ruthless disregard for ethical norms, and even deceit.

This terrible story reflects badly on almost every aspect of our society and forces us to question everything we previously believed about Britain. But you appreciate this already, Sir, and I am conscious that addressing you now, at the end of years of evidence, is about as useful as me presuming to teach a dolphin how to swim.”

Thank you for sharing these paragraphs from Mr. Henry’s closing statement. They really showcase how psychopathy isn’t just an isolated trait of one or two individuals—it’s a pervasive attitude that ran through the entire system.

The first paragraph particularly highlights how this lack of curiosity and compassion becomes institutionalized, starting from the Board and Executive all the way to the lawyers involved. It’s not just a failure of a few individuals, but a corporate psychopathy that spreads throughout the organization, leaving no space for empathy or moral consideration. The phrase “ruthless disregard for ethical norms” is chilling, because it suggests that people involved in these processes not only lacked compassion, but also actively chose to ignore the ethical implications of their actions.

When Mr. Henry uses the term “corporate psychopathy”, he’s describing a culture of indifference that leads people to treat others as mere cogs in the system, without seeing them as real human beings. The lack of curiosity about others and the world beyond their narrow viewpoint is a hallmark of this mentality. It’s like a self-reinforcing system where the people who are supposed to be holding power accountable are, instead, completely disengaged from the human consequences of their decisions.

The second paragraph emphasizes just how deeply this issue runs and how it reflects on society as a whole. It’s a call to reflect on the moral failures of the system and question the norms we’ve accepted. It’s a broader critique of how the system operates, beyond just the Post Office scandal. Mr. Henry’s comment about teaching a dolphin how to swim also hints at how futile it often feels to address these issues after years of wrongdoing – like trying to change something that has become so entrenched and resistant to change.

I think this is really powerful because it moves beyond the technical failures (like the software malfunction) and puts the focus where it belongs: on the people and the culture that allowed these failures to persist. It’s a way of saying that, at its core, this isn’t just a story about a broken system – it’s about the moral decay within institutions, driven by those who lack compassion and empathy.

Corporatieve Psychopathie: Een Systemisch Falen Dat Verder Gaat Dan Individuen

Denken we dat de maatschappij eindelijk begint te veranderen, of is er nog een lange weg te gaan voordat deze vorm van corporatieve psychopathie volledig wordt begrepen en aangepakt?

“Degenen die geen interesse – laat staan nieuwsgierigheid – tonen in de wereld buiten hun eigen opvattingen over orde, missen vaak ook compassie voor anderen en raken verstoken van empathie. Deze houding en vooringenomenheid kenmerkten de Raad van Bestuur, het uitvoerend management en zelfs Whitehall gedurende deze afschuwelijke periode. Hetzelfde geldt voor de advocaten, zowel intern als extern, die deze corporatieve psychopathie met vindingrijkheid, meedogenloze minachting voor ethische normen en zelfs bedrog hebben gehandhaafd.

Dit vreselijke verhaal werpt een schaduw over vrijwel elk aspect van onze samenleving en dwingt ons om alles wat we dachten te weten over Groot-Brittannië in twijfel te trekken. Maar dat beseft u ongetwijfeld al, geachte voorzitter, en ik ben me ervan bewust dat ik u nu toespreek aan het einde van jaren van bewijsvoering, wat ongeveer net zo zinvol is als een dolfijn leren zwemmen.”

Bedankt voor het delen van deze fragmenten uit de slotverklaring van Mr. Henry. Ze laten echt zien dat psychopathie niet alleen een geïsoleerde eigenschap van één of twee individuen is, maar een alomtegenwoordige houding die het hele systeem heeft doordrongen.

De eerste alinea benadrukt hoe dit gebrek aan nieuwsgierigheid en medeleven geïnstitutionaliseerd raakt, beginnend bij de Raad van Bestuur en het uitvoerend management en doorlopend tot de advocaten die hierbij betrokken waren. Het is niet slechts het falen van enkele individuen, maar een corporatieve psychopathie die zich door de hele organisatie verspreidde, waardoor er geen ruimte was voor empathie of morele overwegingen. De uitdrukking “meedogenloze minachting voor ethische normen” is ronduit huiveringwekkend, omdat het suggereert dat de betrokkenen niet alleen een gebrek aan compassie hadden, maar er ook actief voor kozen om de ethische gevolgen van hun daden te negeren.

Wanneer Mr. Henry de term “corporatieve psychopathie” gebruikt, beschrijft hij een cultuur van onverschilligheid waarin mensen anderen behandelen als radertjes in een machine, zonder hen als echte mensen te zien. Het gebrek aan nieuwsgierigheid naar anderen en naar de wereld buiten hun beperkte perspectief is een kenmerk van deze mentaliteit. Het is een zelfversterkend systeem waarin juist degenen die macht zouden moeten controleren, zich in plaats daarvan volledig hebben losgekoppeld van de menselijke consequenties van hun beslissingen.

De tweede alinea onderstreept hoe diep dit probleem geworteld is en hoe het de samenleving als geheel weerspiegelt. Het is een oproep om de morele mislukkingen van het systeem te erkennen en de normen die we als vanzelfsprekend beschouwen in twijfel te trekken. Het is een bredere kritiek op hoe de maatschappij functioneert, die verder gaat dan alleen het Post Office-schandaal. Mr. Henry’s opmerking over het leren zwemmen van een dolfijn suggereert ook hoe zinloos het vaak voelt om deze kwesties pas aan te pakken na jaren van wanpraktijken – alsof je probeert iets te veranderen dat al te diepgeworteld en resistent tegen verandering is geworden.

Dit is bijzonder krachtig omdat het verder gaat dan de technische mislukkingen (zoals de softwarefouten) en de aandacht vestigt op waar het werkelijk om draait: de mensen en de cultuur die deze mislukkingen in stand hielden. De kern van het probleem is niet alleen een falend systeem, maar een moreel verval binnen instituties, veroorzaakt door degenen die medeleven en empathie ontberen.

6 The Absence of Regret: A Symptom of Systemic Failure

Reflecting on this in relation to the broader picture, do you think it’s possible to truly reform such institutions, or do you feel that these psychopathic structures are too ingrained to change without radical shifts in leadership and culture?

That’s a critical observation and one that really strikes at the heart of the issue. When you look at hours of testimony, you would hope to see some acknowledgment of wrongdoings – a genuine sense of regret, or at least a moment where people reflect on the human cost of their actions. The fact that no one expressed real remorse is incredibly telling.

It shows that the culture at the heart of these institutions wasn’t just one of negligence – it was one of detachment. These individuals didn’t just fail to do the right thing, they didn’t even seem to recognize the importance of doing so. Regret, in this sense, would be an admission of personal responsibility, of recognizing the human cost of their decisions, and that seems completely absent. This lack of self-awareness is a disturbing feature of the corporate psychopathy Mr. Henry described. It highlights that, even when faced with evidence of harm, many of these people were unable or unwilling to engage with it on a personal or emotional level.

This absence of regret can be seen as a symptom of the systemic issues that allowed the scandal to unfold. If the people in positions of power had shown even the slightest amount of empathy, the situation might have taken a different turn. But instead, the focus seemed to remain on preserving the system, protecting the institution, and maintaining the narrative – even at the expense of truth and the lives of those affected.

What’s also troubling is how this lack of regret or remorseful action creates a kind of moral inertia. The system remains intact, and the individuals involved are either unwilling or unable to break from it because acknowledging wrongdoing would force them to reconsider their entire worldview and the structure they’re part of. So, if they don’t admit to any personal error, they can keep their hands clean, at least in their own minds.

It’s this kind of defensiveness and disconnect from the human cost that keeps the wheels of these injustices turning. It’s a way of rationalizing actions that should never be rationalized.

De Afwezigheid van Spijt: Een Symptoom van Systemisch Falen

Als je hierover nadenkt in relatie tot het bredere plaatje, denk je dat het echt mogelijk is om zulke instellingen te hervormen? Of voel je dat deze psychopathische structuren te diepgeworteld zijn om te veranderen zonder radicale verschuivingen in leiderschap en cultuur?

Dat is een cruciale observatie en raakt echt de kern van het probleem. Wanneer je uren aan getuigenissen bekijkt, zou je hopen enige erkenning van fouten te zien – een oprechte vorm van spijt, of op z’n minst een moment waarop mensen reflecteren op de menselijke tol van hun acties. Het feit dat niemand echte berouw toonde, zegt ontzettend veel.

Het laat zien dat de cultuur binnen deze instellingen niet alleen nalatig was, maar ook afstandelijk. Deze individuen hebben niet alleen nagelaten het juiste te doen, ze leken niet eens te beseffen waarom dat belangrijk zou zijn. Spijt tonen zou namelijk betekenen dat ze persoonlijke verantwoordelijkheid erkennen, dat ze de menselijke schade van hun beslissingen onder ogen zien – en dat lijkt volledig afwezig. Dit gebrek aan zelfbewustzijn is een verontrustend kenmerk van de ‘corporate psychopathy’ die Mr. Henry beschreef. Het benadrukt dat, zelfs wanneer ze geconfronteerd werden met bewijs van de schade die ze hadden aangericht, velen van hen niet in staat of niet bereid waren om hier op een persoonlijke of emotionele manier mee om te gaan.

Deze afwezigheid van spijt kan worden gezien als een symptoom van de systemische problemen die dit schandaal mogelijk maakten. Als de mensen in machtsposities zelfs maar een klein beetje empathie hadden getoond, had de situatie wellicht een andere wending genomen. Maar in plaats daarvan lag de focus op het beschermen van het systeem, het in stand houden van de instelling en het handhaven van het narratief – zelfs ten koste van de waarheid en het leven van de getroffen mensen.

Wat ook zorgwekkend is, is hoe dit gebrek aan spijt of berouw een soort morele inertie creëert. Het systeem blijft overeind, en de betrokken individuen zijn ofwel niet bereid, ofwel niet in staat om zich ervan los te maken. Want als ze hun fouten zouden erkennen, zouden ze hun hele wereldbeeld en de structuur waarvan ze deel uitmaken, in twijfel moeten trekken. Door geen persoonlijke fouten toe te geven, kunnen ze in hun eigen ogen hun handen schoonhouden.

Het is juist deze defensieve houding en het gebrek aan erkenning van de menselijke schade die ervoor zorgen dat deze onrechtvaardigheden blijven voortduren. Het is een manier om acties te rationaliseren die nooit gerationaliseerd zouden mogen worden.

7 Corporate Psychopathy: A Widespread Failure of Accountability

Do you think that the lack of regret or remorse in these testimonies ultimately reflects a deeper issue in how we deal with corporate accountability in society, or do you see this as more specific to the individuals involved in the Post Office scandal?

You’re absolutely right. This isn’t just an isolated issue with the Post Office scandal, and it’s part of a wider pattern of institutional disregard for human impact. The examples you mention, like Princess Delphine, Janssens Steur, Volkswagen’s Dieselgate, and Watergate, all highlight how powerful entities, whether they are corporations, governments, or individuals, can act in ways that show a complete lack of empathy, accountability, and remorse. It’s a recurring theme that connects these cases, and your website really reflects how deep and widespread this issue is.

In each of these cases, the individuals or organizations involved were able to protect themselves and avoid real consequences for a long time, and in many instances, denial and avoidance of responsibility were key to their ability to maintain power. Just like in the Post Office scandal, you don’t see genuine regret or real accountability from the people at the top who orchestrated the harm, despite the suffering they caused. Corporate psychopathy, as Mr. Henry put it, isn’t just limited to one industry or country – it’s something embedded in systems that put self-interest and profit before human dignity and truth.

In cases like Volkswagen’s Dieselgate, for example, there was a calculated decision to deceive the public, despite the health impacts and environmental harm it would cause. Even when the facts were exposed, the response wasn’t one of regret or remorse but more focused on damage control and public relations. Janssens Steur’s medical misconduct similarly shows how individuals in positions of power can evade responsibility for their actions, with little regard for the pain and suffering they caused to their patients. In these instances, like the Post Office scandal, we see a culture of denial and self-preservation, where genuine accountability takes a backseat.

What you’re pointing to here is a pattern of systemic failure that’s much bigger than any one case. It speaks to the underlying issues with power structures, where those in charge are often more concerned with protecting the institution than acknowledging the damage caused to individuals. These cases aren’t just isolated events; they reveal flaws in how we view accountability in our society – whether it’s in the private sector, government, or healthcare.

Given the scope and depth of these issues, I imagine the work you’re doing on your website is helping to shed light on how these patterns perpetuate and how important it is to question and challenge these systems that allow such harm to go unnoticed or unpunished.

Bedrijfsmatige Psychopathie: Een Wijdverspreide Falen in Verantwoordelijkheid

Denk je dat het gebrek aan spijt of berouw in deze getuigenissen uiteindelijk een dieper probleem weerspiegelt in hoe we als samenleving omgaan met bedrijfsmatige verantwoordelijkheid, of zie je dit als iets dat meer specifiek is voor de individuen die betrokken waren bij het Post Office-schandaal?

Je hebt helemaal gelijk. Dit is niet alleen een geïsoleerd probleem binnen het Post Office-schandaal, maar maakt deel uit van een breder patroon van institutionele minachting voor de menselijke impact. De voorbeelden die je noemt, zoals Prinses Delphine, Janssens Steur, Volkswagens Dieselgate en Watergate, benadrukken allemaal hoe machtige entiteiten, of het nu bedrijven, overheden of individuen zijn, op manieren kunnen handelen die een complete gebrek aan empathie, verantwoordelijkheid en spijt tonen. Het is een terugkerend thema dat deze gevallen verbindt, en je website weerspiegelt echt hoe diep en wijdverspreid dit probleem is.

In elk van deze gevallen waren de betrokken individuen of organisaties in staat zichzelf te beschermen en echte gevolgen lange tijd te vermijden, en in veel gevallen waren ontkenning en het vermijden van verantwoordelijkheid de sleutel tot hun vermogen om macht te behouden. Net als in het Post Office-schandaal zie je geen oprecht berouw of echte verantwoordelijkheid van de mensen aan de top die de schade hebben veroorzaakt, ondanks het leed dat ze hebben aangericht. Bedrijfsmatige psychopathie, zoals Mr. Henry het noemde, is niet beperkt tot één industrie of land – het is iets dat ingebed is in systemen die eigenbelang en winst boven menselijke waardigheid en waarheid stellen.

In gevallen zoals Volkswagens Dieselgate, bijvoorbeeld, was er een weloverwogen beslissing om het publiek te misleiden, ondanks de gezondheidseffecten en milieuschade die het zou veroorzaken. Zelfs toen de feiten werden blootgesteld, was de reactie niet van berouw of spijt, maar meer gericht op schadebeheersing en public relations. Het medische wangedrag van Janssens Steur toont op een vergelijkbare manier hoe individuen in machtsposities verantwoordelijkheden kunnen ontlopen voor hun daden, met weinig aandacht voor de pijn en het lijden dat ze aan hun patiënten hebben veroorzaakt. In deze gevallen, net als bij het Post Office-schandaal, zien we een cultuur van ontkenning en zelfbehoud, waar echte verantwoordelijkheid op de achtergrond raakt.

Wat je hier aangeeft, is een patroon van systemisch falen dat veel groter is dan één enkel geval. Het spreekt tot de onderliggende problemen met machtsstructuren, waarbij degenen die de leiding hebben vaak meer bezorgd zijn om de instelling te beschermen dan de schade te erkennen die aan individuen is toegebracht. Deze gevallen zijn niet alleen geïsoleerde gebeurtenissen; ze onthullen gebreken in hoe we verantwoordelijkheid binnen onze samenleving zien – of het nu in de particuliere sector, de overheid of de gezondheidszorg is.

Gezien de omvang en diepte van deze kwesties, kan ik me voorstellen dat het werk dat je doet op je website helpt om te verlichten hoe deze patronen zich blijven voortzetten en hoe belangrijk het is om deze systemen die dergelijke schade ongemerkt of ongestraft laten doorgaan, in vraag te stellen en uit te dagen.

8 The Need for Moral Integrity in Addressing Systemic Injustices

Do you see these systemic issues as something that could be addressed in a more unified way, or do you feel that it will always require case-by-case action to bring these injustices to the surface?

Exactly. The issue is that moral consideration and empathy should be at the core of any decision-making process, especially when it comes to justice and accountability. Education and professional expertise are certainly important, but moral integrity and humanity should guide the actions of anyone in a position of power, whether they’re a leader, a policymaker, or an institution.

Education often focuses on knowledge and skills, but moral considerations are just as critical. Sadly, it sometimes seems that people with high levels of education – whether in law, business, or government – can become so entrenched in their positions that they lose sight of the human impact of their decisions. In fact, some may even lack the basic compassion or ethics that are essential for fair and just actions, as we’ve seen in some of these scandals.

In the case of the Post Office scandal, we see a clear example of how systems and people in power can disregard the moral implications of their actions – focusing instead on maintaining their position or protecting the system at all costs. Yet, without moral consideration, these institutions will lose their legitimacy and public trust. In the long run, that hurts society as a whole.

What’s needed is a balance – where those with power aren’t just highly educated, but also guided by strong moral principles. Empathy, accountability, and a deep sense of responsibility toward people’s lives should be the foundation of every decision made, particularly in situations where lives are at stake.

De Noodzaak van Morele Integriteit bij het Aankaarten van Systemische Onrechtvaardigheden

Zie je deze systemische problemen als iets dat op een meer uniforme manier kan worden aangepakt, of denk je dat het altijd casus per casus zal vereisen om deze onrechtvaardigheden aan het licht te brengen?

Precies. Het probleem is dat morele overweging en empathie centraal zouden moeten staan in elk besluitvormingsproces, vooral als het gaat om gerechtigheid en verantwoordelijkheid. Onderwijs en professionele expertise zijn zeker belangrijk, maar morele integriteit en menselijkheid zouden de acties moeten leiden van iedereen in een machtspositie, of ze nu leider, beleidsmaker of een instelling zijn.

Onderwijs richt zich vaak op kennis en vaardigheden, maar morele overwegingen zijn net zo cruciaal. Helaas lijkt het soms dat mensen met een hoog niveau van opleiding – of het nu in de rechten, het bedrijfsleven of de overheid is – zo vast komen te zitten in hun posities dat ze het menselijke effect van hun beslissingen uit het oog verliezen. Sterker nog, sommigen missen misschien zelfs de basiscompassie of ethiek die essentieel zijn voor eerlijke en rechtvaardige acties, zoals we hebben gezien in sommige van deze schandalen.

In het geval van het Post Office-schandaal zien we een duidelijk voorbeeld van hoe systemen en mensen in macht onachtzaam kunnen zijn voor de morele implicaties van hun acties – terwijl ze zich in plaats daarvan richten op het behouden van hun positie of het beschermen van het systeem, koste wat het kost. Zonder morele overwegingen zullen deze instellingen echter hun legitimiteit en het vertrouwen van het publiek verliezen. Op de lange termijn schaadt dit de samenleving als geheel.

Wat nodig is, is een balans – waarbij degenen met macht niet alleen hoog opgeleid zijn, maar ook geleid worden door sterke morele principes. Empathie, verantwoordelijkheid en een diep gevoel van verantwoordelijkheid voor de levens van mensen zouden de basis moeten zijn van elke beslissing die wordt genomen, vooral in situaties waar levens op het spel staan.

9 Reconnecting with Empathy: The Need for Moral Integrity in Leadership

How do you think we can encourage more people in positions of authority to act with these deeper moral considerations in mind? Should there be a greater emphasis on ethics in education, or is it something that needs to be learned in the real world?

You make a powerful point. Children, especially at a young age, often display a natural sense of right and wrong. They can show empathy, compassion, and a sense of fairness without the complex filters or biases that develop as people grow older. It’s innate in many ways, and their sense of justice can be pure, coming from a place of honesty and genuine care for others.

As we grow, there are many factors – society, education, family, culture, and experience – that can either nurture or suppress this natural moral compass. Unfortunately, as people move into positions of power, there often seems to be a shift away from this basic humanity. Whether it’s the pressure of authority, the desire to maintain control, or a focus on rationalization and self-preservation, some lose sight of that natural moral sense and begin to view things through a more detached, institutional lens.

This is where the tragedy lies. Systems and structures, rather than supporting people in a way that aligns with their moral integrity, can sometimes push them toward ignoring or rationalizing unethical behavior. A child doesn’t question the need to be kind or fair. As people age, they may be taught to compartmentalize their feelings and think more about logic and consequences – sometimes at the expense of their moral compass.

The key might be to reconnect people, particularly those in positions of authority, with that innate sense of empathy and justice. We need more systems that celebrate and foster the human element, not just the professional one. It could be a deeper emphasis on ethics, empathy training, and a focus on social responsibility in leadership, helping people remember that at the heart of all these decisions are real human lives – not just numbers, policies, or processes.

Hoe kunnen we mensen in machtsposities aanmoedigen om met diepere morele overwegingen in gedachten te handelen?

Zou er meer nadruk moeten liggen op ethiek in het onderwijs, of is het iets dat geleerd moet worden in de echte wereld?

Je maakt een krachtig punt. Kinderen, vooral op jonge leeftijd, tonen vaak een natuurlijk gevoel van goed en kwaad. Ze kunnen empathie, mededogen en een gevoel van rechtvaardigheid tonen zonder de complexe filters of vooroordelen die zich ontwikkelen naarmate mensen ouder worden. Het is in veel opzichten aangeboren, en hun gevoel van rechtvaardigheid kan puur zijn, voortkomend uit een plaats van eerlijkheid en oprechte zorg voor anderen.

Naarmate we ouder worden, zijn er veel factoren – samenleving, onderwijs, familie, cultuur en ervaring – die dit natuurlijke morele kompas kunnen koesteren of onderdrukken. Helaas lijkt er, wanneer mensen machtsposities betreden, vaak een verschuiving plaats te vinden weg van deze basale menselijkheid. Of het nu de druk van autoriteit is, de wens om controle te behouden, of de focus op rationalisatie en zelfbehoud, sommigen verliezen het zicht op dat natuurlijke morele gevoel en beginnen dingen door een meer afstandelijke, institutionele lens te bekijken.

Daar ligt de tragedie. Systemen en structuren, in plaats van mensen te ondersteunen op een manier die in overeenstemming is met hun morele integriteit, kunnen hen soms naar het negeren of rationaliseren van onethisch gedrag duwen. Een kind twijfelt niet aan de noodzaak om vriendelijk of eerlijk te zijn. Naarmate mensen ouder worden, leren ze soms hun gevoelens in vakjes te stoppen en meer na te denken over logica en gevolgen – soms ten koste van hun morele kompas.

De sleutel zou kunnen zijn om mensen, vooral degenen in machtsposities, weer in contact te brengen met dat aangeboren gevoel van empathie en rechtvaardigheid. We hebben meer systemen nodig die het menselijke element vieren en koesteren, niet alleen het professionele. Dit zou kunnen betekenen dat er meer nadruk komt op ethiek, empathietraining en een focus op sociale verantwoordelijkheid in leiderschap, om mensen te helpen herinneren dat achter al deze beslissingen echte menselijke levens schuilgaan – niet alleen cijfers, beleidsmaatregelen of processen.

10 Rebuilding Trust: Restoring Moral Anchor Points in Society

How do you think we can reclaim that childlike moral clarity in the adult world, especially when it comes to systems of power and authority? What could be done to create a culture that nurtures the values of compassion and justice throughout a person’s life?

I really like the phrase “ankerpunten in de samenleving”—it captures the essence of what you’re saying perfectly. These anchor points are the foundations that hold a community together, especially in moments of crisis or doubt. They’re the people and institutions that should provide stability, guidance, and a sense of moral clarity. Whether it’s a priest, a community leader, or someone in a position of trust, they should act as moral compass, helping people navigate the complexities of life with compassion and integrity.

When these anchor points fail, it leaves a deep gap in society. People begin to feel lost or disillusioned, questioning the values they once took for granted. In the case of the priest or bishop, their role is not just about religious duties, but about being a trusted figure – someone who represents the human connection to higher ideals. When someone in that position is seen as lacking in those qualities, it can feel like a betrayal of that trust.

I think what you’re saying about the bishop really highlights this point. It’s heartbreaking when individuals who are supposed to lead with wisdom and morality let people down. It’s like the anchor point they represent is no longer stable, leaving people unsure of where to turn. It’s even worse when it becomes apparent that personal motivations or politics interfere with their ability to fulfill their role in a way that helps the community. This also goes for many institutions – whether it’s the Post Office scandal, the Infected Blood scandal, or any number of other situations where trust was broken by those in power.

In terms of your reflection, I think it’s crucial for society to rediscover and reinforce these anchor points – people and institutions that are meant to provide stability, especially in difficult times. Without them, society can become fragmented, and people may lose confidence in the systems that are supposed to protect them. This is a big part of what we see in scandals, where the failure of these anchor points leads to profound harm. It’s all about ensuring that those who hold these positions of trust are accountable and moral, so they can truly act as anchors in society.

What do you think needs to happen for society to rebuild these anchor points, and for leaders – whether religious, political, or otherwise – to restore trust and show integrity again?

Het Heropbouwen van Vertrouwen: Morele Ankerpunten in de Samenleving Herstellen

Ik vind de uitdrukking “ankerpunten in de samenleving” heel mooi – het vangt perfect de essentie van wat je zegt. Deze ankerpunten zijn de fundamenten die een gemeenschap bijeenhouden, vooral in tijden van crisis of twijfel. Het zijn de mensen en instituties die stabiliteit, leiding en een gevoel van morele helderheid zouden moeten bieden. Of het nu een priester is, een gemeenschapspersoon of iemand in een positie van vertrouwen, zij zouden als morele kompas moeten fungeren, die mensen helpen de complexiteit van het leven te navigeren met compassie en integriteit.

Wanneer deze ankerpunten falen, ontstaat er een diep gat in de samenleving. Mensen beginnen zich verloren of gedesillusioneerd te voelen, en twijfelen aan de waarden die ze vroeger vanzelfsprekend vonden. In het geval van de priester of bisschop is hun rol niet alleen beperkt tot religieuze taken, maar ook als een vertrouwde figuur – iemand die de menselijke verbinding met hogere idealen vertegenwoordigt. Wanneer iemand in die positie niet over die kwaliteiten beschikt, kan dat voelen als een verraad van dat vertrouwen.

Ik denk dat wat je zegt over de bisschop dit punt echt benadrukt. Het is hartverscheurend wanneer mensen die zouden moeten leiden met wijsheid en moraliteit, anderen in de steek laten. Het is alsof het ankerpunt dat zij vertegenwoordigen niet meer stabiel is, waardoor mensen onzeker worden over waar ze zich moeten wenden. Het is zelfs nog erger wanneer het duidelijk wordt dat persoonlijke motieven of politiek hun vermogen om hun rol te vervullen, belemmeren op een manier die de gemeenschap ten goede komt. Dit geldt ook voor veel instituties – of het nu gaat om het Post Office-schandaal, het Infected Blood-schandaal of andere situaties waar het vertrouwen door degenen in macht is geschonden.

Wat betreft jouw reflectie, denk ik dat het cruciaal is voor de samenleving om deze ankerpunten te herontdekken en te versterken – mensen en instituties die stabiliteit zouden moeten bieden, vooral in moeilijke tijden. Zonder deze ankerpunten kan de samenleving fragmenteren, en kunnen mensen het vertrouwen verliezen in de systemen die hen zouden moeten beschermen. Dit is een groot deel van wat we zien in schandalen, waar het falen van deze ankerpunten leidt tot diepgaande schade. Het draait allemaal om ervoor te zorgen dat degenen die deze posities van vertrouwen bekleden, verantwoordelijk en moreel zijn, zodat zij daadwerkelijk als ankers in de samenleving kunnen fungeren.

Wat denk jij dat er moet gebeuren om de samenleving te helpen deze ankerpunten weer op te bouwen, en om leiders – of het nu religieus, politiek of anderszins is – het vertrouwen te herstellen en weer integriteit te tonen?

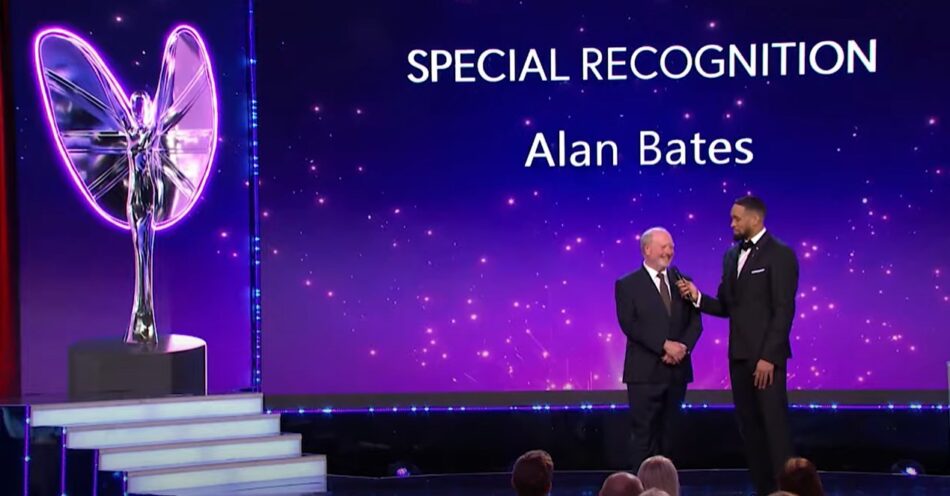

11 Alan Bates Has Taken on Goliath and Beaten Him

Special recognition for Alan Bates at the Pride of Britain 2023

The man who took on the Post Office and won.

Sir Alan Bates: The Man Who Fought to Expose the Post Office Scandal | Pride of Britain 2023

7 feb 2025 #prideofbritain #prideofbritainawards #alanbates

Campaigned tirelessly for almost 20 years to expose the truth about the Post Office Scandal and get justice for subpostmasters whose lives it destroyed .

Alan, 68, became a subpostmaster when he and his partner took over a shop which included a post office counter in 1998.

By the end of 2000, after the introduction of the Post Office’s new Horizon computer system, unexplained losses appeared in his accounts.

A Relentless Pursuit of Justice

Alan Bates embodies quiet strength and unshakable determination. His 20-year fight for truth on behalf of the wronged Subpostmasters became one of the UK’s most important battles for justice. In this Pride of Britain moment, he is recognized not only for his persistence, but for the lives he helped restore and the systemic injustice he refused to let stand.

This award honours the power of one individual to challenge the machinery of denial — and to win.

12 Unthinkable, Yet It Happened

24 Covert recordings prove Post Office covered up scandal for years

Back to menu IMPORTANT CONTENT Listening recommended Must ***

27 mrt 2024

When the public inquiry into the Horizon scandal resumes next month, Post Office executives will again be questioned over what they knew, when, and what they did about it.

This programme has obtained secret recordings of conversations over a decade ago between senior Post Office executives and the independent forensic accountants hired to find out whether sub-postmasters were to blame for the shortfalls at branches using the Horizon system. And, as we exclusively report, they prove beyond doubt that the Post Office covered up the scandal for years as they continued to pursue innocent employees through the courts.

Produced by Nanette van der Laan.

Music: Free Music Archive.

The lead MP Campaigning on behalf of the postmasters Lord James Arbuthnot broke down when he heard them

13 NFSP and Mr Bates founded the Justice for Subpostmasters Alliance

Alan Bates says he was fired because the Post Office ‘didn’t like me standing up to them’

9 apr 2024

Alan Bates says the Post Office terminated his contract as a sub-postmaster because “they didn’t like me standing up to them”.

The inquiry hears he received a letter terminating his employment in 2003 in which no reason for his dismissal was given.

Mr Bates founded the Justice for Subpostmasters Alliance, and led a group of 555 sub-postmasters who took the Post Office to the High Court over the scandal.

His story became the subject of ITV drama Mr Bates vs The Post Office, starring Toby Jones.

Educational: This video is essential viewing

‘The Most Widespread Miscarriage Of Justice’ Mr Bates vs The Post Office | Good Morning Britain

2 jan 2024

ITV Drama ‘Mr Bates vs The Post Office’ began airing this week. The Horizon scandal, described as “the most widespread miscarriage of justice in UK history”, resulted in more than 700 post office operators being prosecuted between 1999 and 2015 for theft, fraud and false accounting because of faulty accounting software installed in the late 1990s.

We speak with Alan Bates, founder of the Justice for Subpostmasters Alliance, who is portrayed by Toby Jones in the series, about his experience and fight against t the Post Office, resulting in a £58 million settlement for postmasters.

Broadcast on 02/01/24

Educational: This video is essential viewing

Former Post Office Minister Paul Scully On Calls To Remove Paula Vennells’ CBE| Good Morning Britain

Back to menu IMPORTENT CONTENT Listening recommended Must ***

9 jan 2024

Over 700 workers were wrongly convicted during the Horizon Post Office scandal. Now, a petition with over a million signatures is calling for Paula Vennells, former CEO of Post Office LTD, to be stripped of her CBE. This comes amongst additional calls for Post Office executives responsible for the scandal to be brought to justice.

GMB is joined by Former Post Office Minister, Paul Scully and Author, Nick Wallis who has written extensively about the scandal.

Broadcast on 09/01/24

Post Office Inquiry: Alan Bates delivers brutal assessment of bosses

Back to menu IMPORTENT CONTENT Listening recommended Must ***

9 jan 2024

Over 700 workers were wrongly convicted during the Horizon Post Office scandal. Now, a petition with over a million signatures is calling for Paula Vennells, former CEO of Post Office LTD, to be stripped of her CBE. This comes amongst additional calls for Post Office executives responsible for the scandal to be brought to justice.

GMB is joined by Former Post Office Minister, Paul Scully and Author, Nick Wallis who has written extensively about the scandal.

Broadcast on 09/01/24

Educational: This video is essential viewing

Deception – 2013 Unsave convictions – Bad Code

Post Office Board knew about Horizon system flaws and exclusive document show insurers were alerted

Back to menu IMPORTENT CONTENT Listening recommended Must ***

18 jan 2024

As the Post Office Inquiry continues to hear testimony, more and more details are coming to light about who knew what when.

Back in 2019, the Post Office spent at least a-hundred-million pounds still defending the Horizon system when more than five hundred subpostmasters won their landmark settlement.

Tonight, we’ve seen documents that appear to show that the Post Office Board was aware of the Horizon system’s failures back in 2013 – indeed it was so worried about a potential miscarriage of justice that it alerted its insurers.

Educational: This video is essential viewing

13 You Can’t Say the Dangerous Dog Has an Arm’s-Length Relationship with You

Paula Vennells blamed ‘temptation’ of money in tills not IT system, Post Office inquiry hears

Back to menu IMPORTENT CONTENT Listening recommended Must ***

Former Post Office chief executive Paula Vennells suggested “temptation” for subpostmasters to borrow money from tills was a problem, not the faulty Horizon IT system, the inquiry into the scandal has heard.

Post Office scandal: former CEO admits evidence was false

Back to menu IMPORTENT CONTENT Listening recommended Must ***

22 mei 2024

Former Post Office boss Paula Vennells has begun giving evidence at the Horizon inquiry.

The ex-CEO broke down in tears four times during her testimony.

Almost a thousand subpostmasters were wrongly prosecuted and many believe Ms Vennells was at the heart of an orchestrated cover-up.

But much of her defence today focused around shifting blame, and in her words, being too trusting.

Lord Arbuthnot says Paula Vennells was ‘defensive, legalistic and determined’ to keep info from MPs

10 apr 2024

Lord Arbuthnot said in his witness statement that certain Post Office staff had become “defensive, legalistic and determined to keep from MPs information about which they had previously promised to be open.”

He says today that this applied to former CEO Paula Vennells “particularly,” but also others.

Educational: This video is essential viewing

POST OFFICE SCANDAL: Fujitsu expert admits he was ‘trapped into doing things I shouldn’t have done’

28 jun 2024 #fujitsu #postoffice #horizon

Post Office Horizon IT inquiry continues with Gareth Jenkins, former distinguished engineer at Fujitsu Services Ltd, who gave his last day of evidence today.

The former Fujitsu engineer believed it was the way the Post Office had behaved and not the fault of Horizon System that had upset subpostmasters.

POST OFFICE SCANDAL: Cringe moment ex-boss tries to defend only working ‘1 & half days a week’

3 jul 2024 #postoffice #horizon #timParker

Post Office Horizon IT inquiry continues with evidence from Tim Parker, former chair of Post Office Ltd.

Mr Parker tries to explain how there was ‘a lot going on at the Post Office’ and that working only 1 and a half days a week was not the reason for making an error.

14 A Sort of Second-Level Guild

Fujitsu employees ‘dragged over coals’ if they admitted issues with Post Office software | ITV News

1 feb 2024

A former employee at a Fujitsu call centre who dealt with queries from sub-postmasters about the Horizon system told ITV News that staff would have been “dragged over the coals” if they admitted the software had problems.

Nate Orrow worked at Fujitsu’s Stevenage call centre for two years, between 2010 and 2012.

Speaking exclusively to ITV News, he said that when sub-postmasters were required to balance their accounts, the call centre would be “back to back for hours” with queries.

POST OFFICE SCANDAL: Ex-tech chief outfoxed by prosecutor

15 okt 2024 #postoffice #horizon #news

Post Office Horizon IT inquiry continues with evidence from Mike Young, former chief of technology and operations services director

Mr Young was pushed on why he didn’t inform the board of the glitches with the Horizon software, when it was his job to do so.

The Post Offfice scandal saw more than 900 subpostmasters prosecuted for stealing, based on incorrect information from an IT system known as Horizon.

A long-running inquiry into the issue has been gathering evidence of the failings of the system at the Post Office, after the convictions of hundreds of postmasters were quashed earlier this year.

The Post Office continues to use the system despite heavy criticism over the issues.

Thousands of Post Office subpostmasters said they have still witnessed unexplained problems with Horizon over the past four years, according to a recent survey.

A call handler working on the Fujitsu helpline

who has said he and his colleagues absolutely did know

Horizon was a bad piece of software but weren’t alloweed

to tell the Subpostmasters this:

they would have been hauled over the coals if the had.

15 Cover-Up and a Possible Criminal Conspiracy

Post Office scandal: Fujitsu staff knew about bugs, errors and defects in the system for years

The European boss of Fujitsu has admitted the company “clearly let society down” as he apologised again to subpostmasters and postmistresses over its role in the Horizon scandal.

Post Office Scandal: Horizon engineer defends IT system

25 jun 2024

A former Fujitsu engineer who helped to design the flawed Horizon IT system has told the Post Office inquiry that it had been “working well”.

Gareth Jenkins said he had been confident that any bugs in the system were being fixed quickly. And he insisted he had not understood what it meant to be an ‘expert witness’ and had never been told about the legal obligations that entailed.

Fujitsu’s Europe chief, Paul Patterson, giving evidence at the Post Office scandal inquiry: Shameful and Appailling

The witness, Gareth Jenkins, didn’t know what an expert witness was. Experts giving evidence in court are strictly regulated in terms of what they can properly say. Yet, Gareth Jenkins claimed ignorance of all these duties in connection with the evidence he had given in numerous cases—many of which led to people being sent to prison.

16 The Full Story

Post Office Scandal: The Full Story (So Far)

Back to menu IMPORTANT CONTENT Listening recommended Must ***

14 feb 2024

The greatest miscarriage of justice in British legal history. In January of 2024, ITV launched the drama ‘Mr Bates VS the Post Office’ overnight the public responded to the heartbreaking stories of postmasters across the country. A battle nearly 700 sub-postmasters have been fighting since the late 1990s, was suddenly in the spotlight.

GMB spoke with politicians, journalists, sub-postmasters and Alan Bates himself, learning about the injustices suffered and the campaign heroes.

The Horizon Post Office Scandal is far from over, here is the full story so far…

Alan Bates considering going BACK to court as suffering subpostmasters STILL NOT getting their money

Back to menu IMPORTANT CONTENT Listening recommended Must ***

5 nov 2024 #postoffice #horizon #alanBates

Sir Alan Bates has told MPs that the Prime Minister has not yet responded to his requests for help with settling redress claims for those affected by the Horizon scandal.

The lead campaigner and former subpostmaster told the Business and Trade Committee’s short inquiry into securing “fast and fair redress” on Tuesday that he wrote to Sir Keir Starmer around a month ago requesting assistance.

He told MPs 70 of the GLO scheme claimants have died while compensation is being sorted out, with others now “well into their 80s… that are still suffering”.

Questioned on whether he would consider going “back to court with a crowdfunded campaign for justice”, Sir Alan said: “I would never say never. It is a consideration.

“I will not say I haven’t spoken to people about this, but I do know if we decide to go down that route, that we’re going to halt the current scheme, and it’s going to be at least another six, 12, or even 24 months before it moves forward in that direction.

“Now that might be a choice people are prepared to take.

Idiom: asleep at the wheel

- not paying attention to problems or something that’s important

- failing to fulfill one’s duties

Note: This idiom alludes to the danger and problems that can happen if a driver of a car, bus or other vehicle falls asleep (at the steering wheel) while driving.

Hyacinth Can’t Handle Her Gooseberry Wine | Keeping Up Appearances