PART 2

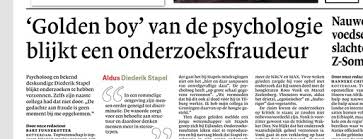

Diederik Stapel, a prominent Dutch social psychologist, until the summer 2011

Page Description

Explore injustice exemplified by Diederik Stapel’s ‘Science Fraud’. How he deceived with fabricated data, revealing the darker side of academic integrity.

Introduction

Science is built on trust – a trust that researchers seek truth and uphold integrity in their pursuit of knowledge. But what happens when this trust is betrayed? The term science fraud describes the deliberate falsification, fabrication, or manipulation of research data, a practice that undermines not only individual studies but the very foundation of scientific progress.

This page examines the phenomenon of science fraud through the infamous case of Diederik Stapel, a Dutch psychologist whose fabricated studies rocked the academic world. Stapel’s actions serve as a stark reminder of the consequences of prioritizing prestige over principles. Here, we explore the methods, motivations, and impact of such deceit, shedding light on how it erodes public trust and distorts our understanding of critical issues.

Join us in uncovering the lessons from one of the most audacious scandals in scientific history, and consider the broader implications for accountability and reform in academia.

Wetenschap is gebouwd op vertrouwen – het vertrouwen dat onderzoekers de waarheid nastreven en integriteit hooghouden in hun zoektocht naar kennis. Maar wat gebeurt er wanneer dat vertrouwen wordt geschonden? De term wetenschapsfraude verwijst naar de opzettelijke vervalsing, fabricatie of manipulatie van onderzoeksgegevens, een praktijk die niet alleen individuele studies ondermijnt, maar ook de fundamenten van wetenschappelijke vooruitgang.

Deze pagina onderzoekt het fenomeen wetenschapsfraude aan de hand van de beruchte zaak van Diederik Stapel, een Nederlandse psycholoog wiens gefabriceerde studies de academische wereld op zijn kop zetten. Stapels daden zijn een scherpe herinnering aan de gevolgen van het stellen van prestige boven principes. Hier verkennen we de methoden, motivaties en impact van dergelijke misleiding, en belichten we hoe dit het publieke vertrouwen schaadt en ons begrip van cruciale kwesties verstoort.

Doe met ons mee in het blootleggen van de lessen uit een van de meest gedurfde schandalen in de wetenschappelijke geschiedenis, en overweeg de bredere implicaties voor verantwoordelijkheid en hervormingen binnen de academische wereld.

1 How one man got away with mass fraud by saying ‘trust me, it’s science’

When news broke this year that Diederik Stapel, a prominent Dutch social psychologist, was faking his results on dozens of experiments, the fallout was swift, brutal and global.

Science and Nature, the world’s top chroniclers of science, were forced to retract papers that had received wide popular attention, including one that seemed to link messiness with racism, because “disordered contexts (such as litter or a broken-up sidewalk and an abandoned bicycle) indeed promote stereotyping and discrimination.”

As a result, some of Prof. Stapel’s junior colleagues lost their entire publication output; Tilburg University launched a criminal fraud case; Prof. Stapel himself returned his PhD and sought mental health care; and the entire field of social psychology — in which human behaviour is statistically analyzed — fell under a pall of suspicion.

One of the great unanswered questions about the Stapel affair, however, is how he got away with such blatant number-fudging, especially in a discipline that claims to be chock full of intellectual safe-guards, from peer review to replication by competitive colleagues. How can proper science go so wrong?

The answer, according to a growing number of statistical skeptics, is that without release of raw data and methodology, this kind of research amounts to little more than “‘trust me’ science,” in which intentional fraud and unintentional bias remain hidden behind the numbers. Only the illusion of significance remains.

Diederik Alexander Stapel is a former Tilburg professor of social psychology who became known as a science fraudster.

Science fraud based on fictitious data is suddenly exposed after almost 10 years (October 2011). Stapel got his Ph.D. in 1997.

In 1991 he graduated cum laude in psychology and communication science at the University of Amsterdam, where he obtained his doctorate in social psychology in 1997. The KNAW then immediately appointed him as academic researcher.

From 2000, he was a professor at the University of Groningen and from 2006 at Tilburg University.

Diederik Stapel spent years sitting at his kitchen table putting together datasets and tweaking the numbers to arrive at the conclusion he had come to.

He had not even been to the locations where the scientific research was to take place!

Two young students and a young professor notice what is going on by the inconsistencies in the numbers.

The three young whistle-blowers do the necessary. This is the core of the denouement.

Wetenschapsfraude op basis van fictieve gegevens wordt plots na bijna 10 jaar ontmaskerd (oktober 2011). Stapel got his Ph.D. in 1997.

In 1991 studeerde hij cum laude af in de psychologie en in de communicatiewetenschap aan de Universiteit van Amsterdam, waar hij in 1997 promoveerde in de sociale psychologie. Daarna stelde de KNAW hem meteen aan als academieonderzoeker.

Vanaf 2000 was hij hoogleraar aan de Rijksuniversiteit Groningen en vanaf 2006 aan de Universiteit van Tilburg.

Diederik Stapel steekt jarenlang aan de keukentafel datasets in elkaar en tweakt de getallen om aan de vooropgestelde conclusie te komen.

Hij was zelfs niet op de locaties geweest waar de wetenschappelijk onderzoek zou plaats vinden!

Twee jonge studenten en een jonge professor merken wat er gaande is door de inconsistenties in de getallen.

De drie jonge klokkenluiders doen het nodige. Dit is de kern van de ontknoping.

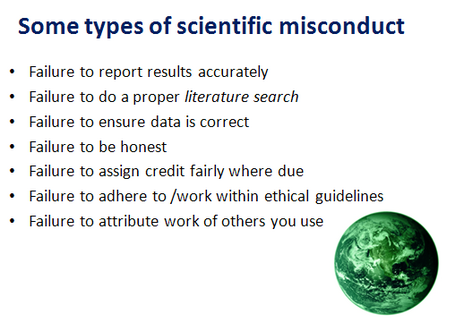

Definition Fraud, cheating in research, or research misconduct, which is the official term, is often defined as fabrication, falsification and plagiarism.

On Diederik Stapel’s former website, on the ‘derailment’ page, there was the following striking sentence:

…chooses the wrong path and gradually deceives himself to ultimately crash hard

Op de vroegere website van Diederik Stapel stond er op de pagina ‘ontsporing’ volgende treffende zin:

‘… het verkeerde pad kiest en zichzelf stukje bij beetje een rad voor ogen draait om uiteindelijk keihard te verongelukken’.

2 Fraud and plagiarism

It may be tempting to dress up in borrowed plumage (plagiarise/refrain from referring to one’s sources), cook data (falsify data) or simply invent (fabricate) data, and disregard the fact that this violates fundamental and internationally accepted rules for good research practice.

Scientific misconduct is defined as falsification, fabrication, plagiarism and other serious breaches of good research practice that have been committed wilfully or through gross negligence when planning, carrying out or reporting on research (italics added).

Diederik Stapel was a Dutch social psychologist who became infamous for academic fraud. Here are some key points about him:

Stapel was born on October 19, 1966, in the Netherlands. He earned a Ph.D. in social psychology from the University of Amsterdam in 1997 and went on to become a professor at several universities in the Netherlands.

In 2011, Stapel was exposed for fabricating data in his research. He had been conducting experiments on topics such as stereotypes, prejudice, and social influence, but it was later discovered that he had made up much of the data to support his hypotheses.

Stapel’s fraud was uncovered after an investigation by Tilburg University, where he was a professor at the time. The investigation found that he had fabricated data in at least 55 of his published papers.

Stapel’s fraud was considered particularly egregious because he had manipulated data in such a way that it supported his preconceived ideas. He had also falsified data in multiple experiments to produce consistent results, further deceiving the scientific community.

After his fraud was exposed, Stapel resigned from his position at Tilburg University and was banned from conducting research or teaching in the Netherlands. He also faced legal consequences, including a fine and community service.

Stapel’s case drew attention to the issue of academic fraud and the pressures faced by researchers to produce positive results. It also sparked a broader discussion about the need for more transparency and reproducibility in scientific research.

Stapel has since written a book about his experiences, titled “Ontsporing” (“Derailment” in English), in which he reflects on his motivations and the societal factors that contributed to his fraud.

1 Car Paint Job Surprise

31 mrt. 2011

Pedestrians are pranked into looking like they just ruined a car paint job! A presentation of the Just For Laughs Gags. The funny hidden camera pranks show for the whole family. Juste pour rire les gags, l’émission de caméra caché la plus comique de la télé!

The article in the New York Times (next webpage)

is based on a clear view of the problem of fraud by Diederik Stapel.

Het artikel in de New York Times (volgende webpagina) geeft een mooi beeld,

het geeft op makkelijke wijze inzicht in de wetenschapsfraude door Diederik Stapel.