When the pain and suffering

afflict you and you are weighed

down by what is happening

to you, then you face reality.

Wanneer de pijn en het lijden

je teistert en je gebukt gaat

door wat er met je gebeurt

dan zie je de realiteit onder

ogen.

Een schreeuw die door merg en been gaat

A cry that pierces the marrow and bone

A screem of pain and horror

hair-raising

causing terror, excitement, or astonishment

hair-raising stories

Merriam Webster

The expression “A Hair Raising Scream!” is an idiomatic phrase that is often used to describe a scream that is particularly intense, startling, or frightening. The key points of this expression would typically revolve around the following:

Intensity: The scream is described as “hair-raising,” implying that it is extremely intense and has a strong impact on the senses. It suggests that the scream is loud, piercing, and potentially terrifying.

Emotion: The scream is likely to be accompanied by strong emotions, such as fear, panic, or distress. It may convey a sense of urgency or danger, and may be evoked by a shocking or horrifying event.

Physical sensation: The phrase “hair-raising” suggests a physical sensation, as if the scream caused the hairs on the body to stand on end. This can further emphasize the intensity and impact of the scream.

Startle or surprise: The scream is unexpected and catches people off guard, causing them to react with shock or surprise. It may come suddenly, without warning, and elicit a startled response from those who hear it.

Context-dependent: The key points of “A Hair Raising Scream!” would also depend on the specific context in which it is used. For example, in a horror story, it may refer to a scream from a ghost or a monster, while in a comedy, it may refer to a humorous or exaggerated scream for comedic effect.

Overall, the key points of the expression “A Hair Raising Scream!” revolve around the intense, emotional, and potentially frightening nature of the scream, which is described as having a strong impact on the senses and causing a startled or shocked reaction.

One cannot imagine the clumsy way in which, with no respect for the rules, a decision is sometimes reached in legal proceedings.

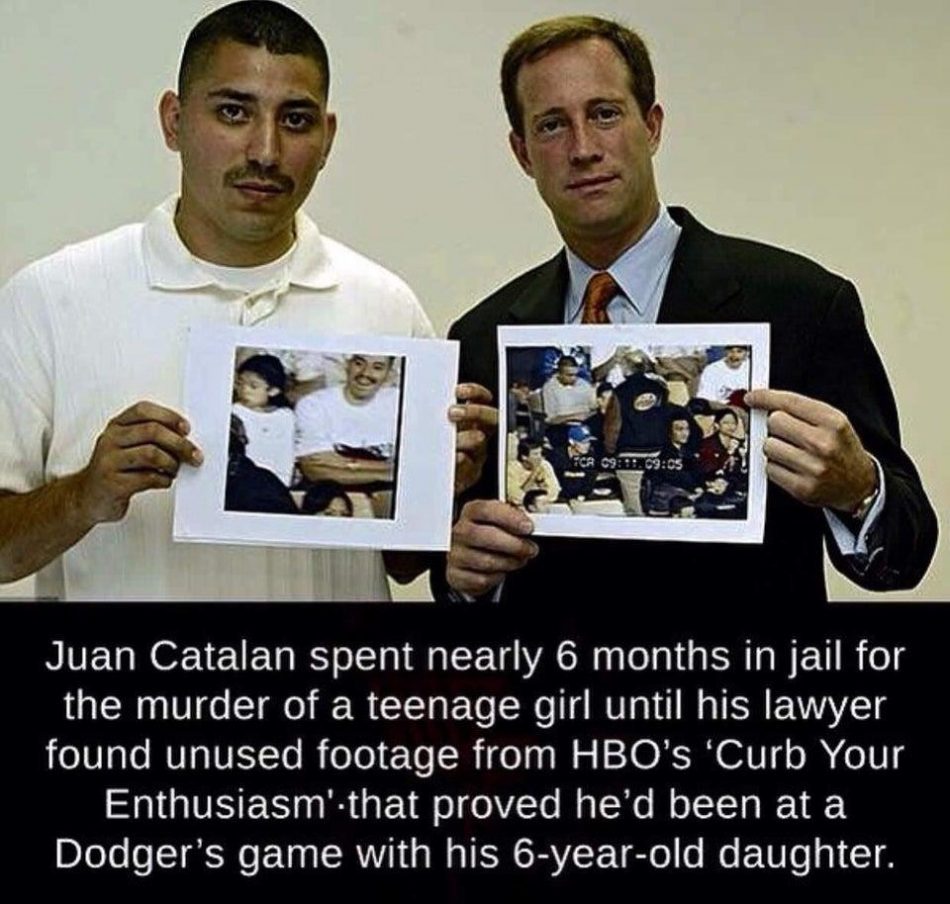

Juan Catalan forgives police who framed him for murder he didn’t commit | 60 Minutes Australia

4 sep. 2018

The Juan Catalan case involved a rush to judgment by law enforcement officials and prosecutors that resulted in him being wrongfully accused of murder. Some key points of the case include:

In 2003, a 16-year-old girl was shot and killed in Los Angeles, and police suspected that the killer was Juan Catalan, a local man with a criminal record.

Despite a lack of physical evidence connecting Catalan to the crime, detectives and prosecutors became convinced of his guilt based on a witness statement and cell phone records that placed Catalan near the crime scene at the time of the shooting.

Catalan maintained his innocence, but was arrested and charged with murder. He faced the death penalty if convicted.

Catalan’s defense team obtained evidence that showed he had been at a Los Angeles Dodgers baseball game with his daughter at the time of the murder. However, the prosecution argued that this alibi was fabricated.

Catalan’s defense team then obtained footage from an episode of HBO’s “Curb Your Enthusiasm” that had been filmed at the baseball game, and which showed Catalan and his daughter in the crowd. This provided clear and indisputable evidence that Catalan could not have committed the murder.

The prosecution eventually dropped the charges against Catalan, and he was released after spending over five months in jail.

Catalan later filed a lawsuit against the City of Los Angeles and the LAPD, alleging that they had violated his civil rights by falsely accusing him of murder. The case was settled for $320,000.

The Juan Catalan case highlights the dangers of a rush to judgment in criminal investigations, and underscores the importance of thorough investigation and the preservation of exculpatory evidence.

It can happen to anyone

How could it have come to this, that of the nearly 800 people in the extreme examples on the first four web pages (button 1 to 4), no one has done anything wrong and the judiciary – by the way it operates – makes a complete mess of those people’s lives?

Innocent children end up on the electric chair just like that. These are examples of extreme situations of making fun of people for no reason, occasion or cause.

It is a modus operandi that has points in common with Diederik Stapel’s science fraud.

They are confrontational questions we need to ask ourselves.

Het kan iedereen overkomen

Hoe is het zover kunnen komen, dat van de nagenoeg 800 personen in de extreme voorbeelden op de eerste vier webpagina’s (button 1 tot 4) niemand iets verkeerd heeft gedaan en justitie – maakt door de wijze waarop ze te werk gaat – van het leven van die mensen een complete puinhoop?

Onschuldige kinderen komen zomaar op de elektrische stoel. Het zijn voorbeelden van extreme situaties van mensen voor de gek houden, zonder reden, aanleiding of oorzaak.

Het is een werkwijze die raakpunten heeft met de wetenschapsfraude van Diederik Stapel.

Het zijn confronterende vragen die we ons dienen te stellen.

Excerpt from The New York Times about Diederik Stapel’s ‘Science Fraud’

At the end of November, the universities unveiled their final report at a joint news conference: Stapel had committed fraud in at least 55 of his papers, as well as in 10 Ph.D. dissertations written by his students. The students were not culpable, even though their work was now tarnished. The field of psychology was indicted, too, with a finding that Stapel’s fraud went undetected for so long because of “a general culture of careless, selective and uncritical handling of research and data.” If Stapel was solely to blame for making stuff up, the report stated, his peers, journal editors and reviewers of the field’s top journals were to blame for letting him get away with it. The committees identified several practices as “sloppy science” – misuse of statistics, ignoring of data that do not conform to a desired hypothesis and the pursuit of a compelling story no matter how scientifically unsupported it may be.

The adjective “sloppy” seems charitable. Several psychologists I spoke to admitted that each of these more common practices was as deliberate as any of Stapel’s wholesale fabrications. Each was a choice made by the scientist every time he or she came to a fork in the road of experimental research – one way pointing to the truth, however dull and unsatisfying, and the other beckoning the researcher toward a rosier and more notable result that could be patently false or only partly true. What may be most troubling about the research culture the committees describe in their report are the plentiful opportunities and incentives for fraud. “The cookie jar was on the table without a lid” is how Stapel put it to me once. Those who suspect a colleague of fraud may be inclined to keep mum because of the potential costs of whistle-blowing.

Fragment uit The New York Times over Diederik Stapel’s ‘Wetenschapsfraude’

Eind november onthulden de universiteiten hun eindrapport tijdens een gezamenlijke persconferentie: Stapel had gefraudeerd met minstens 55 van zijn proefschriften, en met 10 proefschriften van zijn studenten. De studenten waren niet schuldig, ook al was hun werk nu bezoedeld. De psychologie werd ook aangeklaagd, met de bevinding dat Stapel’s fraude zo lang onopgemerkt bleef vanwege “een algemene cultuur van onzorgvuldig, selectief en onkritisch omgaan met onderzoek en gegevens”. Als Stapel de enige schuldige was voor het verzinnen van dingen, zo stelde het rapport, dan waren het zijn collega’s, redacteuren en reviewers van de toptijdschriften in het vakgebied, die hem daarmee weg lieten komen. De comités noemden verschillende praktijken als “sloppy science” – verkeerd gebruik van statistieken, negeren van gegevens die niet overeenkomen met een gewenste hypothese en het nastreven van een overtuigend verhaal, hoe wetenschappelijk ongefundeerd dat ook moge zijn.

Het adjectief “slordig” lijkt mild. Verscheidene psychologen die ik sprak gaven toe dat elk van deze meer gebruikelijke praktijken even opzettelijk was als Stapel’s verzinsels in het groot. Elk van deze praktijken was een keuze van de wetenschapper, telkens wanneer hij of zij op een tweesprong van experimenteel onderzoek kwam – de ene weg wees naar de waarheid, hoe saai en onbevredigend die ook was, en de andere weg wenkte de onderzoeker naar een rooskleuriger en opmerkelijker resultaat, dat overduidelijk onwaar of slechts gedeeltelijk waar kon zijn. Wat misschien het meest verontrustend is aan de onderzoekscultuur die de comités in hun rapport beschrijven, zijn de overvloedige mogelijkheden en stimulansen voor fraude. “De koekjestrommel stond op tafel zonder deksel”, zo zei Stapel eens tegen mij. Wie een collega verdenkt van fraude kan geneigd zijn te zwijgen vanwege de mogelijke kosten van klokkenluiden.

“A Hair Raising Scream!” is an exclamation or expression typically used to describe a loud, high-pitched scream that is so intense and frightening that it causes the hair on one’s body to stand up. This expression is often used in situations that evoke fear or horror, such as in scary movies, haunted houses, or real-life situations that are terrifying.

The key points of this expression would be:

Intensity: The scream is described as “hair-raising,” which suggests that it is so intense and scary that it causes the hair on one’s body to stand up. It implies a high level of fear or terror.

Loudness: The scream is described as being loud, which implies that it is not only intense but also audible from a distance. It could be heard by others nearby, adding to the sense of terror.

Emotion: The scream is likely to be a response to a highly emotional or frightening situation, such as seeing a ghost or being attacked by a monster. The person screaming is likely to be experiencing intense fear or terror.

Context: The use of this expression suggests that the situation is extremely scary or horrific. It is often used in the context of horror movies, haunted houses, or other situations that are designed to scare or terrify people.

Overall, the key points of the expression “A Hair Raising Scream!” emphasize the intensity, loudness, and emotional impact of a scream that is caused by a frightening or horrific situation.

Charles Spencer On BBC Failings: ‘Diana Did Lose Trust In Key People’

1 Two remarkable examples of large-scale failure are:

The Post Office Wrongful Convictions Scandal

2 The Duke Lacrosse Case:

3 Turning a blind eye by the police

4 Turning a blind eye by the BBC and police

The key points of the expression “A Hair Raising Scream!” are:

Intensity: The scream is described as “hair raising,” which conveys a sense of extreme intensity. It suggests that the scream is so powerful or frightening that it literally causes one’s hair to stand on end, due to the intensity or horror of the situation.

Fear or Terror: The word “scream” implies a loud and piercing vocalization made when someone is in a state of fear, terror, or extreme emotion. The expression suggests that the scream is particularly alarming or chilling, evoking a strong emotional response from those who hear it.

Physical Reaction: The reference to “hair raising” suggests a physical reaction to fear or shock. When a person is frightened or alarmed, their hair may stand on end due to the involuntary contraction of the tiny muscles attached to their hair follicles, resulting in a tingling or prickling sensation on the skin.

Vividness: The use of vivid language in the expression, such as “hair raising” and “scream,” creates a sensory image that can evoke a visceral response in the reader or listener, adding intensity and drama to the description of the event or situation.

Exaggeration: The use of hyperbolic language, such as “hair raising,” is a form of exaggeration, emphasizing the extreme nature of the situation or the intensity of the emotion being conveyed. It adds emphasis and impact to the expression, making it more memorable and attention-grabbing.

How to: Street Golf – Lesson 1

18 sep. 2012