Er was eens een tijd van stille toewijding, vertrouwen en menselijke waardigheid — vóór de duisternis van het onrecht viel. Deze pagina vertelt hoe dat alles verloren ging, en over de onverzettelijke strijd om het weer terug te winnen.

Before the darkness of injustice descended, there was a time of quiet service, trust, and dignity. This page tells the story of how it was lost — and the enduring fight to reclaim it.

Alan Bates became the face of the fight against the injustices of the Post Office. His story has come to define those of at least 736 others who were also wrongfully convicted between 1999 and 2015.

Customers at Jo Hamilton’s post office could buy a slice of cake from the attached cafe before purchasing their stamps. Her story is one of the central themes of the ITV drama.

Page Description

Explore the British Post Office scandal — a true story of injustice, betrayal, and the key figures behind one of the greatest miscarriages of justice.

Understanding the British Post Office Scandal

Once upon a time, a trusted institution became the architect of one of Britain’s greatest injustices.

The British Post Office scandal is not just a story of technical failure, but of lives shattered, trust betrayed, and truth suppressed.

This page offers a clear and comprehensive overview, based on the professional documentary ‘The British Post Office Scandal: Worse than you Know,’ which brings the key figures, crucial events, and lasting consequences into focus.

Justitie op Eén Been: De Gekantelde Weegschaal van Gerechtigheid

In een ideale wereld staat justitie onwrikbaar, gefundeerd in waarheid en integriteit. Maar wat gebeurt er wanneer justitie wankelt en onstabiel op één been balanceert? Ze wordt hol, neigt niet langer naar eerlijkheid, maar naar onbalans, verwaarlozing en onrecht. Voor Liam Allan, een criminologiestudent die onterecht beschuldigd werd, en talloze anderen zoals hij, laat dit scheve systeem een onuitwisbaar merkteken achter – een last van schuld die nooit had mogen bestaan.

Hier onderzoeken we die momenten waarop justitie faalt, wanneer ze rust op een fundament dat niets anders is dan vergissing en nalatigheid. Deze verhalen onthullen de werkelijke prijs van een ongebalanceerd rechtssysteem – een systeem dat, in plaats van eerlijkheid te brengen, vaak de onschuldigen belast met een schuld die nooit volledig kan worden weggenomen.

The village shop and Post Office run by Jo Hamilton, former Subpostmistress from South Warnborough, Hampshire. She was wrongfully accused of stealing £36,000 due to faults in the Horizon IT system.

South Warnborough, Hampshire

The British Post Office Scandal: Worse than you Know

The Reckoning Has Begun—But Justice Is Not Yet Done

The documentary lays bare what many tried to keep hidden: how a state-owned institution weaponised its own software flaws against the very people who kept it running. The question remains: how could this happen for so long?

Private prosecutions. A helpline that lied. A refusal to answer legitimate questions—like the duplicates Allan Bates identified in his shortfall. For over a decade, Subpostmasters were told, “You are the only one,” while the Post Office systematically destroyed their lives. And now, during the inquiry, we hear again and again: “I didn’t know then what I know now.” But where is the accountability? Where is the sincere regret?

And so we must face the truth:

In the UK, many people only came to understand the scale of the injustice through the broadcast of Bates vs The Post Office. For decades, the truth was buried beneath legal denials, corporate deflections, and institutional silence. But when the human suffering was finally shown to millions, it became undeniable. The nation was confronted not with a scandal in the abstract, but with real lives—destroyed by a system that refused to listen.

Yet public awareness is not the same as justice.

The suffering of tens of thousands of Subpostmasters has not been undone.

Compensation schemes and legal exonerations may offer partial redress, but they cannot restore the stolen years, the lost dignity, or the shattered trust.This was not merely a failure of software. It was a failure of conscience.

The reckoning has begun. But it is not finished. And it must not be allowed to fade.

What cannot be forgotten is the wrong software at the heart of this nightmare—Horizon. But it became more than just a technical issue. It became a moral failure when everyone, from executives to lawyers and IT personnel, was either forced or complicit in playing along: continuing to accuse, while knowing—or being able to know—that the system itself was flawed.

James Arbuthnot and others tried to raise the alarm. They called for clarity, for independent investigations. But they were ignored, silenced, or deliberately obstructed.

This was not just a judicial miscarriage. It was an organized silence around a lie that destroyed the lives of tens of thousands.

De Afrekening Is Begonnen—Maar Gerechtigheid Is Nog Niet Voltooid

De documentaire onthult wat velen jarenlang verborgen hielden: hoe een staatsbedrijf zijn eigen softwarefouten wendde tegen de mensen die het draaiende hielden. De vraag blijft: hoe kon dit zo lang doorgaan?

Privévervolgingen. Een hulplijn die loog. Een structurele weigering om eerlijke vragen te beantwoorden—zoals de duplicaten die Alan Bates ontdekte in zijn tekort van 6.000 pond, dat plots werd teruggebracht naar 1.200. Hij kreeg geen uitleg. Subpostmasters kregen jarenlang te horen: “U bent de enige,” terwijl de Post Office doelbewust hun levens verwoestte. En nu, tijdens het onderzoek, horen we keer op keer: “Dat wist ik toen niet.” Maar waar is de verantwoording? Waar is de oprechte spijt?

En dus moeten we de waarheid onder ogen zien:

In het Verenigd Koninkrijk werd de ware omvang van deze gerechtelijke dwaling pas duidelijk voor een groot publiek na de uitzending van Bates vs The Post Office. Decennialang werd de waarheid begraven onder juridische ontkenningen, institutionele arrogantie en stilzwijgen. Maar toen het menselijke leed eindelijk aan miljoenen mensen werd getoond, werd het onweerlegbaar. De samenleving werd niet geconfronteerd met een abstract schandaal, maar met echte levens—verwoest door een systeem dat weigerde te luisteren.

Toch is publieke bewustwording nog geen gerechtigheid.

Het lijden van tienduizenden Subpostmasters is niet verdwenen.

Schadevergoedingsregelingen en juridische eerherstel bieden misschien enige genoegdoening, maar kunnen de gestolen jaren, de verloren waardigheid of het geschonden vertrouwen niet herstellen.Dit was niet slechts een technisch falen. Het was een falen van het geweten.

De afrekening is begonnen. Maar zij is nog niet voltooid. En zij mag nooit in de vergetelheid raken.

Wat niet vergeten mag worden: de foute software die de kern van deze nachtmerrie vormde—Horizon. Maar het werd meer dan alleen een technisch probleem. Het werd een moreel falen toen iedereen, van leidinggevenden tot juristen en IT’ers, gedwongen of gewillig meedeed aan het spel: doorgaan met beschuldigen, terwijl men wist of had kunnen weten dat het systeem zelf fout zat.

James Arbuthnot en anderen probeerden het aan te kaarten. Ze vroegen om duidelijkheid, om onafhankelijk onderzoek. Maar ze werden genegeerd, gesust of bewust tegengewerkt.

Het was niet alleen een gerechtelijke dwaling. Het was een georganiseerd zwijgen rondom een leugen die het leven van tienduizenden mensen verwoestte.

The British Post Office Scandal: Worse than you Know

Time Interval: 00:00:00 – 00:45:03

Summary

🏡 Tragic Start of Martin Griffiths’ Journey

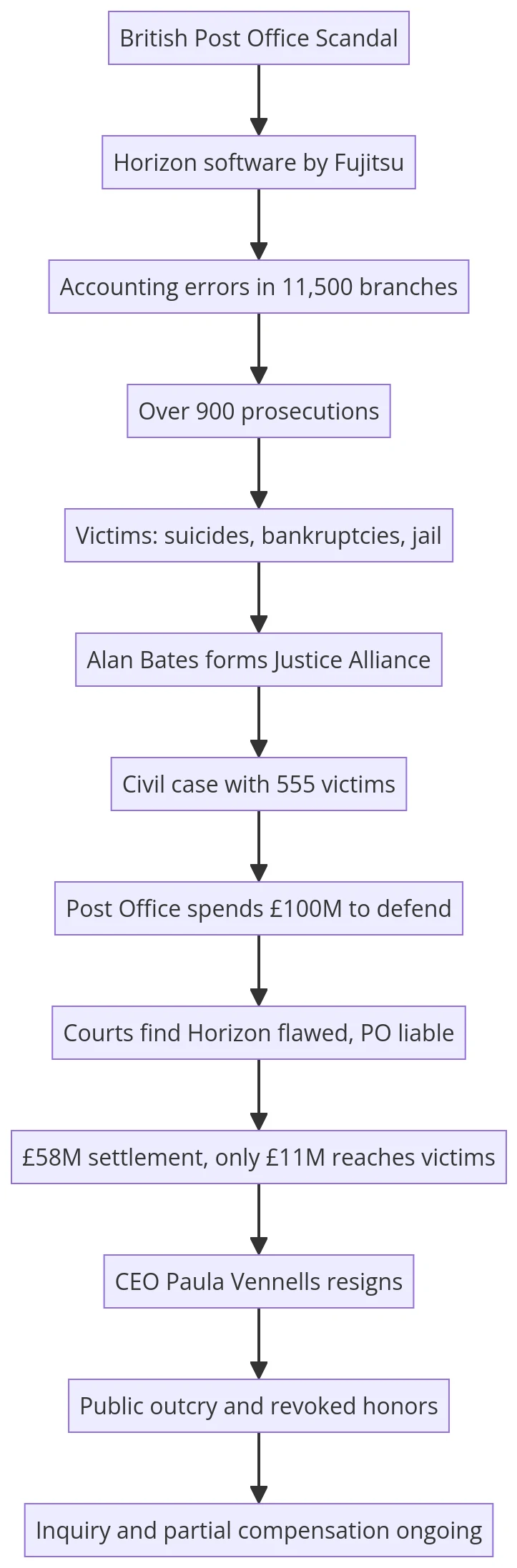

In 1995, Martin Griffiths bought a post office in Ellesmere Port hoping for a peaceful retirement. Instead, by 2013, mounting debts due to faulty accounting software drove him to suicide. His case marks one of the most heartbreaking outcomes of this scandal.💻 Faulty Horizon Software Implanted Nationwide

Horizon, a billion-pound accounting system by Fujitsu, was implemented in 11,500 post offices despite known bugs. The software falsely reported financial shortfalls, ruining lives while executives publicly praised its reliability.🧾 Victims Misled, Prosecuted, and Imprisoned

Sub-postmasters like Jo Hamilton and Lee Castleton were falsely accused of theft based on Horizon’s errors. Many remortgaged homes or went bankrupt; over 900 were prosecuted, with 236 imprisoned, while they were falsely assured they were the only ones with problems.🧠 Severe Mental and Physical Toll

The stress and public shaming led to mental health crises, with several victims becoming severely depressed or suicidal. Some suffered institutionalization or turned to alcohol, while families were torn apart.🕵️ Evidence Suppression and Denial

Fujitsu allegedly manipulated data remotely, contradicting claims of no external access. The Post Office destroyed evidence, denied Horizon flaws, and used settlements to record phantom profits, all while portraying Horizon as robust.⚖️ Alan Bates’ Fight for Justice

Bates, after losing his business, became the face of the Justice for Subpostmasters Alliance (JFSA). He led 555 victims into a civil suit resulting in a £58 million settlement—most of which was eaten up by legal costs.🏛️ Governmental and Corporate Complicity

CEOs like Paula Vennells and Adam Crozier enjoyed promotions and honors despite their roles in the scandal. Vennells walked away with millions, only recently relinquishing her CBE amid public outrage in 2024.📉 Delayed Justice and Limited Compensation

By 2024, only partial compensations have been paid, with most victims receiving far less than their losses. A TV miniseries finally brought widespread attention, and criminal investigations are underway but no arrests have yet been made.

Insights Based on Numbers

💸 £1 Billion: The initial taxpayer investment in Horizon, despite it being known to fail from the start.

⚖️ Over 900 Prosecutions: Between 1999 and 2015, based on Horizon errors.

💀 At Least 4 Suicides: Linked to Horizon-triggered crises.

🏛️ £58 Million Settlement: For 555 victims, but only £11 million reached them (~£20,000 each).

👥 3,500 Victims: Coerced into repaying non-existent shortfalls.

These figures illustrate not just the scale of the miscarriage of justice, but the deep institutional betrayal.

Example Exploratory Questions

How did the Post Office and Fujitsu manage to hide Horizon’s faults for so long? (Enter E1 to ask)

What role did government oversight—or lack thereof—play in perpetuating the scandal? (Enter E2 to ask)

What were the long-term impacts on victims like Alan Bates and Jo Hamilton? (Enter E3 to ask)

Educational article

The British Post Office Scandal: A Full Overview

The video titled “The British Post Office Scandal: Worse than you Know” provides an extensive, harrowing account of one of the largest miscarriages of justice in British history. This article captures the full narrative from its origins to the ongoing quest for justice.

Origins of the Scandal: Horizon Software

In the late 1990s, the UK government partnered with Fujitsu to implement Horizon, a digital accounting system for post offices. With over £1 billion in taxpayer funding, Horizon was plagued from the outset by critical bugs that falsely indicated financial discrepancies in thousands of branches.

The Victims: Sub-Postmasters Under Siege

From 1999 to 2015, over 900 sub-postmasters were wrongly prosecuted for theft, fraud, and false accounting. Many more were coerced into repaying money they never stole. Some went bankrupt, were imprisoned, or took their own lives. Victims were often misled into thinking they were alone.

Systemic Failure and Denial

Despite repeated reports and internal knowledge of Horizon’s flaws, the Post Office continued to defend the system and prosecute innocent people. The Post Office’s top executives suppressed evidence, destroyed documents, and refused to admit errors to protect their positions and reputations.

Alan Bates and the Fight for Justice

Alan Bates, a former sub-postmaster, spearheaded the Justice for Sub-postmasters Alliance. He united 555 victims and, with litigation funding from Therium, launched a class action lawsuit: Bates and Others vs. Post Office Limited.

Legal Turning Points and Settlements

Judge Sir Peter Fraser presided over the civil trials between 2017 and 2019, ultimately ruling that Horizon was unfit and the Post Office was liable. Though the Post Office settled for £58 million, most of it went to legal fees, leaving victims with meager compensation.

Accountability and Public Outrage

CEO Paula Vennells, who earned millions during the scandal, resigned in 2019 but retained high-profile roles and honors. A 2024 TV dramatization reignited public outrage. Following over a million petition signatures, Vennells returned her CBE.

Ongoing Justice and Reflection

Criminal investigations have been launched against Post Office and Fujitsu executives. Compensation schemes have been expanded, but many victims still await full restitution. The scandal underscores the fragility of justice when confronted by institutional power and financial disparity.

Conclusion

The Post Office scandal highlights catastrophic failures in technology, oversight, and ethics. It is a cautionary tale of what happens when bureaucracies prioritize image over truth, and how perseverance by ordinary citizens can lead to justice—even if delayed.

Transcript

The year was 1995, in the small English town of Ellesmere Port, 13 miles south of Liverpool. Forty-one-year-old Martin Griffiths had just bought the Post Office on Hope Farm Road for a whopping £100,000. The purchase was part of his retirement plan — Griffiths intended to settle down in comfort and financial stability by 2019, 24 years later.

But tragically, things didn’t turn out that way.

In fact, Martin’s decision to buy the little Post Office on Hope Farm Road would end up costing him his life — all because of what would become the largest miscarriage of justice in British history.

And yet, in theory, Griffiths’ plan was a good one.

Ninety-nine percent of Post Offices in the UK are handed out as franchises to self-employed individuals called Subpostmasters. The remaining one percent are operated directly by the central company, Post Office Limited. In that sense, the UK Post Office operates a bit like McDonald’s: the central company sells off franchise rights and splits the business revenue with the owners of the individual branches.

The key difference from McDonald’s is that Post Office Limited doesn’t really make a profit. It often runs at a loss and constantly struggles to stay out of the red — especially with the rise of the internet, email, and private shipping companies. Still, the Post Office is regarded in the UK as an essential public service, and so Post Office Limited is propped up by hundreds of millions of pounds in government subsidies every single year.

While the Post Office may look like a private-sector corporation at a glance, it’s actually a company created by an Act of Parliament — functionally beholden to the British government, which is its sole shareholder.

And like many government-run organisations, the UK Post Office has long suffered from inefficiency, incompetence, a bloated bureaucracy, and a shocking lack of accountability — particularly at the top, where senior executives are lavishly paid.

But none of this concerned Martin Griffiths at the time. As a Subpostmaster, he stood to earn a decent income from his share of fees paid by customers for postal, financial, and government ID services, along with revenue from selling greeting cards, stationery, and odds and ends that his wife Gina stocked in the shop.

Griffiths also received a modest salary from the central Post Office, and when the time came, he would be entitled to a pension funded by the government.

For the first 14 years, everything ran smoothly.

Transcript (Edited English – up to 2:15)

The problem started in 2009, when Martin Griffiths was told he had to adopt an accounting system called Horizon to balance his books. Horizon was a program designed by the Japanese IT company Fujitsu. The software had first been introduced in 1999, costing the taxpayer £1 billion — the largest non-military IT contract in Europe at the time. In fact, the Horizon accounting software had been salvaged from a disastrous earlier failure: Fujitsu’s attempt to create a new pensions and welfare payment system, which had already cost the British taxpayer £700 million.

The Horizon system was gradually rolled out to 11,500 privately owned Post Offices over the course of the next decade. By 2009, Griffiths was ordered to adopt it in his small shop. By then, the crippling problems with the Horizon software had already been known to IT experts, hundreds of Subpostmasters, and the Post Office’s executive management for several years.

Soon, Horizon would be the subject of an exposé in the British trade magazine Computer Weekly. Bottom line: the Horizon accounting software consistently messed up its own bookkeeping — it couldn’t balance the accounts. The one single thing the government had paid a billion pounds for it to do, it couldn’t do.

Griffiths was unaware of these issues and simply complied, thinking all would be well. But within days, discrepancies started to appear in his financial records. The software claimed that his little Post Office was taking in much more money each day than he actually was in real business. On paper, it looked like hundreds — sometimes thousands — of pounds were disappearing from Hope Farm Road’s accounts every single week.

Griffiths contacted the Post Office about the issue, but was firmly told that Horizon was working fine and that the shortfalls must be due to user error — his error. This was a blatant lie. Before long, the amounts of money that were unaccounted for prompted the Post Office to call Griffiths in for an interview with an investigator paid by the company. He was not allowed to bring legal representation. During the interview, the investigator alternated between accusing Griffiths of incompetence and outright theft. He then demanded to know how Griffiths would repay the thousands of pounds he allegedly owed.

Griffiths was made to feel like he was the only Subpostmaster in Britain experiencing problems with Horizon. But by 2009, hundreds of Subpostmasters had already faced similar troubles, and IT experts had grown heavily critical of the software.

Ultimately, Martin Griffiths had to pay the money back — a move that wiped out his profits and forced him to dip into his family savings. But the shortfalls continued and became more frequent. Griffiths quickly ran out of his own money and began borrowing from his elderly parents. When they could no longer help him, he took out bank loans at high interest rates.

For the next four years, Griffiths worked full-time for the privilege of losing all his money and sinking deeper into debt. He fell into chronic depression, coming home from work only to stare into space, not wanting to talk, do anything, or go anywhere. His wife tried relentlessly to cheer him up, but nothing helped. Eventually, she took him to a series of doctors, who prescribed antidepressants and arranged counseling — but Griffiths couldn’t engage.

Meanwhile, the problems at the Post Office continued to pile up. Under threat of disciplinary action, lawsuits, and even jail time, Griffiths paid Post Office Limited approximately £102,000 to cover shortfalls fabricated by the faulty Horizon software.

On two occasions, when Griffiths was unable to repay, Post Office Limited suspended his salary, worsening his already dire financial situation.

Then, in July 2013, the central company informed Martin Griffiths that his Subpostmaster contract would be terminated at the end of October. They accused him of theft — a deeply perverse accusation, considering that Post Office Limited was fully aware of the problems with the Horizon software, and that hundreds of Subpostmasters across the United Kingdom had reported similar issues.

Shortly after receiving his termination notice, the Post Office on Hope Farm Road was robbed. Griffiths was attacked with a crowbar and suffered a broken arm. The thieves made off with £10,000 in cash. When Griffiths informed Post Office Limited, he was told he would be personally responsible for repaying the stolen money. Meanwhile, the central company continued to threaten him with lawsuits and potential jail time. Martin Griffiths was bankrupt. His livelihood had been destroyed, and his hopes for the future were in ruins.

On September 23, 2013 — one month before his contract was due to end — Martin deliberately stepped in front of an oncoming bus. He was taken to hospital in critical condition and spent nearly three weeks on life support. He died on October 11, 2013, at the age of 59, never having regained consciousness. He left behind a loving wife and two children.

At minute 7:13

At minute 12:03

Het jaar was 1995, in het kleine Engelse stadje Ellesmere Port, 21 kilometer ten zuiden van Liverpool. De 41-jarige Martin Griffiths had zojuist het postkantoor aan Hope Farm Road gekocht, voor maar liefst £100.000. De aankoop maakte deel uit van zijn pensioenplan — Griffiths wilde zich tegen 2019, 24 jaar later, in alle rust en financiële zekerheid terugtrekken.

Maar tragisch genoeg zou het heel anders lopen.

Martin’s beslissing om dat kleine postkantoor te kopen zou hem uiteindelijk zijn leven kosten — als gevolg van wat bekendstaat als de grootste gerechtelijke dwaling in de Britse geschiedenis.

Toch leek zijn plan in theorie verstandig.

99% van de Britse postkantoren worden uitgegeven als franchise aan zelfstandige ondernemers, die Subpostmasters worden genoemd. Slechts 1% wordt rechtstreeks beheerd door het centrale bedrijf: Post Office Limited. In die zin werkt het Britse postkantoor een beetje zoals McDonald’s: het hoofdkantoor verkoopt franchiserechten en deelt de opbrengsten met de eigenaren van de afzonderlijke vestigingen.

Het grote verschil met McDonald’s is dat Post Office Limited nauwelijks winst maakt. Het draait vaak verlies en voert een voortdurende strijd om uit de rode cijfers te blijven — zeker sinds de opkomst van het internet, e-mail en commerciële koeriersdiensten. Toch wordt het postkantoor in het Verenigd Koninkrijk gezien als een essentiële publieke dienst, en daarom ontvangt Post Office Limited elk jaar honderden miljoenen aan overheidssubsidies.

Hoewel het postkantoor op het eerste gezicht lijkt op een privaat bedrijf, is het in feite een onderneming die is opgericht via een wet van het parlement — en functioneert het in werkelijkheid onder gezag van de Britse overheid, de enige aandeelhouder.

Zoals bij veel overheidsinstanties het geval is, kampt het Britse postkantoor al jaren met inefficiëntie, onbekwaamheid, een opgeblazen bureaucratie en een schrijnend gebrek aan verantwoordelijkheid — vooral aan de top, waar leidinggevenden vorstelijk worden betaald.

Maar Martin Griffiths maakte zich daar op dat moment geen zorgen over. Als Subpostmaster kon hij rekenen op een redelijk inkomen uit zijn deel van de vergoedingen die klanten betaalden voor postdiensten, financiële diensten en officiële identificaties. Daarnaast verdiende hij aan de verkoop van wenskaarten, kantoorartikelen en allerlei kleine spullen die zijn vrouw Gina in de winkel verkocht.

Griffiths kreeg ook een bescheiden salaris van het centrale Post Office en zou bij zijn pensioen een overheidspensioen ontvangen.

De eerste veertien jaar verliep alles vlekkeloos.

Transcript (Edited English – up to 2:15)

Het probleem begon in 2009, toen Martin Griffiths te horen kreeg dat hij een boekhoudsysteem genaamd Horizon moest gaan gebruiken om zijn administratie op orde te houden. Horizon was een programma ontwikkeld door het Japanse IT-bedrijf Fujitsu. De software werd voor het eerst geïntroduceerd in 1999 en kostte de Britse belastingbetaler één miljard pond — het grootste niet-militaire IT-contract in Europa op dat moment. In feite was de Horizon-software gered uit een eerdere rampzalige mislukking: Fujitsu’s poging om een nieuw pensioenen- en uitkeringssysteem te ontwikkelen, wat de belastingbetaler al 700 miljoen pond had gekost.

Het Horizon-systeem werd in de loop van tien jaar geleidelijk uitgerold naar 11.500 particuliere postkantoren. Tegen 2009 kreeg ook Griffiths de opdracht het te implementeren in zijn kleine winkel. Tegen die tijd waren de ernstige problemen met de Horizon-software al jaren bekend bij IT-deskundigen, honderden Subpostmasters en de directie van de Post Office.

Kort daarna zou Computer Weekly, een Brits vakblad, een onthullend artikel publiceren over Horizon. De kern van de zaak: de Horizon-boekhoudsoftware maakte structureel fouten in de administratie — het kon de cijfers niet kloppend krijgen. Het enige waarvoor de overheid een miljard pond had betaald, werkte simpelweg niet.

Griffiths wist niets van deze problemen en volgde gewoon de instructies, in de veronderstelling dat alles goed zou gaan. Maar binnen enkele dagen doken er al onregelmatigheden op in zijn financiële administratie. Volgens de software haalde zijn postkantoor dagelijks veel meer geld binnen dan hij daadwerkelijk ontving. Op papier leek het alsof er wekelijks honderden, soms duizenden ponden verdwenen uit de boekhouding van Hope Farm Road.

Griffiths nam contact op met de Post Office over de fouten in de software, maar kreeg resoluut te horen dat Horizon perfect werkte en dat de tekorten te wijten waren aan gebruikersfouten — dus aan hem. Dit was een regelrechte leugen. Niet veel later werd hij opgeroepen voor een verhoor met een interne onderzoeker, betaald door het hoofdkantoor van de Post Office. Hij mocht geen juridisch advies of vertegenwoordiging meenemen. Tijdens het gesprek wisselde de onderzoeker beschuldigingen van onbekwaamheid af met insinuaties van diefstal. Griffiths werd gevraagd hoe hij van plan was om de duizenden ponden terug te betalen die hij zogenaamd schuldig was.

Hij kreeg het gevoel dat hij de enige Subpostmaster in het hele land was die problemen had met Horizon. Maar al in 2009 waren honderden anderen door dezelfde software in de problemen geraakt, en ook IT-deskundigen hadden inmiddels felle kritiek geuit.

Uiteindelijk moest Martin Griffiths het geld terugbetalen — een beslissing die zijn winst volledig wegvaagde en hem dwong om zijn spaargeld aan te spreken. Maar de tekorten bleven zich voordoen en namen toe in frequentie. Griffiths was snel door zijn eigen middelen heen en begon geld te lenen van zijn bejaarde ouders. Toen ook zij hem niet meer konden helpen, sloot hij bankleningen af tegen hoge rente.

De daaropvolgende vier jaar werkte Griffiths fulltime, alleen maar om steeds meer geld te verliezen en dieper in de schulden te raken. Hij raakte in een chronische depressie: hij kwam thuis van zijn werk, staarde voor zich uit, wilde niet praten, niets doen en nergens heen. Zijn vrouw deed er alles aan om hem op te beuren, maar het hielp niet. Uiteindelijk bracht zij hem naar verschillende artsen, die hem antidepressiva voorschreven en hem doorverwezen naar een therapeut — maar Griffiths kon zich nergens toe zetten.

Ondertussen bleven de problemen op het postkantoor zich opstapelen. Onder dreiging van disciplinaire maatregelen, rechtszaken en zelfs gevangenisstraf, betaalde Griffiths in totaal ongeveer £102.000 aan Post Office Limited — om tekorten te dekken die waren veroorzaakt door gebrekkige software.

Op twee momenten, toen Griffiths het bedrag niet kon ophoesten, besloot Post Office Limited zijn salaris op te schorten, wat zijn financiële situatie alleen maar verder verslechterde.

On September 23, 2013 — one month before his contract was due to end — Martin deliberately stepped in front of an oncoming bus. He was taken to hospital in critical condition and spent nearly three weeks on life support. He died on October 11, 2013, at the age of 59, never having regained consciousness. He left behind a loving wife and two children.

In juli 2013 liet het hoofdkantoor Martin Griffiths weten dat zijn contract als Subpostmaster op 31 oktober zou worden beëindigd. Ze beschuldigden hem van diefstal — een des te perversere aantijging, aangezien Post Office Limited op dat moment volledig op de hoogte was van de problemen met de Horizon-software. Honderden Subpostmasters in het hele Verenigd Koninkrijk hadden soortgelijke moeilijkheden gemeld.

Kort nadat hij zijn ontslagbrief had ontvangen, werd het postkantoor aan Hope Farm Road overvallen. Griffiths werd aangevallen met een koevoet en liep een gebroken arm op. De daders gingen er vandoor met £10.000 in contanten. Toen Griffiths dit meldde aan Post Office Limited, kreeg hij te horen dat hij het gestolen geld zelf moest terugbetalen. Ondertussen bleef het hoofdkantoor hem bedreigen met rechtszaken en mogelijke gevangenisstraf. Martin Griffiths was failliet. Zijn levensonderhoud verwoest, zijn dromen voor de toekomst in puin.

Op 23 september 2013, een maand voordat zijn contract officieel zou aflopen, liep Martin Griffiths opzettelijk voor een aankomende bus. Hij werd in kritieke toestand naar het ziekenhuis gebracht en lag bijna drie weken aan de beademing. Op 11 oktober 2013 overleed hij, 59 jaar oud, zonder ooit het bewustzijn te hebben herwonnen. Hij liet een liefdevolle echtgenote en twee kinderen achter.

Horizon werd in de herfst van 1999 uitgerold naar de eerste Post Office-vestigingen in het Verenigd Koninkrijk.

Alan Bates nam Horizon in gebruik in zijn winkel eind 2000.

Binnen enkele weken zag Bates dat Horizon een tekort van £6.000 rapporteerde, maar Bates wist dat dit geld niet zomaar was verdwenen.

Daarom ging hij zijn winkeltransacties nauwgezet na met een fijne kam en ontdekte dat Horizon meerdere transacties dubbel had geregistreerd. Dit verklaarde ongeveer £4.800 van het tekort.

Bates nam contact op met zijn regiomanager om te vragen wat hij moest doen met de resterende £1.200 die zogenaamd verdwenen was, maar hij kreeg geen antwoord.

In de daaropvolgende jaren bracht Bates het onderwerp steeds opnieuw ter sprake bij elke nieuwe regiomanager, maar zij gaven hem nooit een antwoord.

Bates vroeg ook om toegang tot het Horizon-systeem, zodat hij de gegevens aan de andere kant kon inzien. Zijn verzoeken werden genegeerd.

Ondertussen bleven de tekorten in het Horizon-boekhoudsysteem verschijnen, en Bates weigerde zorgvuldig om de berekeningen van Horizon te accepteren. In plaats daarvan liet hij de rekeningen doorschuiven naar de volgende week.

Op deze manier voorkwam hij dat er officieel werd vastgelegd dat zijn winkel een tekort had, waardoor hij volgens zijn Subpostmasters-contract zelf aansprakelijk zou worden voor het tekort.

Bates weigerde ook om documenten te ondertekenen waarin werd verklaard dat de berekeningen van Horizon accuraat waren.

In 2002 werd het oorspronkelijke tekort van £1.200 uiteindelijk door de Post Office afgeschreven als een oninbare schuld.

Maar er waren nog duizenden ponden aan tekorten die Bates niet erkende.

Daarom werd Bates in 2003 opgedragen om te stoppen met het doorschuiven van zijn rekeningen en de berekeningen van Horizon te accepteren.

Na overleg met een advocaat nam Bates schriftelijk contact op met de Post Office en weigerde, met de reden dat hem dwingen om foutieve berekeningen te accepteren, een schending van zijn contract zou zijn.

Als reactie beëindigde de Post Office het Subpostmasters-contract van Bates met een opzegtermijn van drie maanden, zonder een formele reden te geven.

Bates’s laatste werkdag als Subpostmaster was 5 november 2003.

In feite betekende dit dat meer dan £60.000 van Bates’s zakelijke investering verloren ging.

Op minuut 12:03

Chapter 1

A Man of Detail

The hero of our story is a man named Alan Bates. Back in March 1998, Bates and his partner, Suzanne Cirone, purchased a Post Office in the suburb of Ky Down in the North Wales town. They saw it as a path to financial stability: Suzanne could pursue her interest in art, while Bates could enjoy walking in the picturesque hills of the Welsh countryside.

In addition to the £60,000 they paid for the business, Bates and Cirone also took on the extra costs of renovating the shop—modernizing its electricity and plumbing, and building an extension that increased the floor space by 50%. This new space allowed them to sell retail goods alongside postal services. They invested their entire life savings into the project, hoping it would bring them a steady income and a peaceful, thriving business for decades to come.

It seemed like the recipe for an idyllic life. Bates served as the Subpostmaster, and in 1998 he still did the shop’s accounts by hand.

Meanwhile, in London, a storm was brewing.

The British government had paid the Japanese IT company Fujitsu £700 million to develop a swipe card system, designed so pensioners and welfare recipients could receive payments directly into their bank accounts when visiting their local Post Office. The government awarded this extremely lucrative contract to Fujitsu for two reasons: first, then-Prime Minister Tony Blair was under intense pressure from the Japanese government to do so; and second, Fujitsu had submitted the cheapest bid among all the competing IT firms.

It showed.

The swipe card project was a complete failure, and in May 1999, the plug was pulled. However, to avoid the embarrassment of such an enormous waste of taxpayer money, the government—and more particularly, Post Office management—chose a perverse solution: they paid Fujitsu hundreds of millions more to retrofit the accounting software from the failed swipe card system.

Thus, in these rather squalid circumstances, Horizon was born.

The Horizon software was meant to help local Post Office branches record transactions and balance their accounts electronically. But from the very beginning, Horizon was plagued with bugs. It couldn’t even keep accurate accounts—randomly changing numbers, duplicating transactions, and failing to calculate correct totals. It was, in essence, a billion-pound Excel spreadsheet that didn’t work—worse than useless.

And because of the immense costs involved, neither the Post Office nor Fujitsu was willing to admit publicly how badly the system was failing. If they had, it might have led to the firing of several high-powered, exorbitantly paid executives. Instead, both organizations chose to protect themselves by burying the truth.

In their public statements, Horizon was described as a flawless system that would bring the British postal service into the 21st century.

Horizon was rolled out to the first few Post Office branches in the UK in the autumn of 1999.

Horizon was rolled out to the first few Post Office branches in the UK in the autumn of 1999.

Alan Bates adopted Horizon in his shop in late 2000.

Within weeks, Bates saw that Horizon was reporting a shortfall of £6,000, but Bates knew this money hadn’t just disappeared. So he went over his shop’s transactions with a fine-tooth comb and discovered that Horizon had duplicated multiple transactions in its records. This accounted for about £4,800 of the shortfall.

Bates contacted his area manager to find out what to do about the remaining £1,200 that had allegedly gone missing, but did not get a response.

Over the next few years, whenever a new area manager was appointed, Bates would broach the subject with them, but they never gave him an answer.

Bates also asked for access to the Horizon system so he could see the data that was being recorded at the other end. His requests were ignored.

Meanwhile, the shortfalls continued to appear in the Horizon accounting system, and Bates carefully refused to accept the calculations performed by Horizon, instead rolling over the accounts to the following week. This way, he avoided putting on record that his shop had a shortfall, thus avoiding becoming liable under his Subpostmasters contract to pay the money out of his own pocket.

Bates also refused to sign his name to any documentation that claimed the calculations done by the Horizon system were accurate.

In 2002, the original £1,200 shortfall was finally written off by the Post Office as an irretrievable loss.

But there were thousands more pounds in shortfall that Bates had refused to acknowledge.

Accordingly, in 2003, Bates was ordered to stop rolling over his accounts and to accept Horizon’s calculations.

After consulting with a lawyer, Bates contacted the Post Office in writing and refused, saying that forcing him to accept faulty calculations would violate his contract.

In response, the Post Office terminated Bates’s Subpostmasters contract with three months’ notice, and without giving a formal reason.

Bates’s last day of service as Subpostmaster was November 5, 2003.

It effectively meant that over £60,000 of Bates’s business investment went up in smoke.

Hoofdstuk 1 – Een man van details

De held van ons verhaal is een man genaamd Alan Bates. In maart 1998 kochten Bates en zijn partner Suzanne Cirone een postkantoor in de buitenwijk Ky Down, in een stadje in Noord-Wales. Ze zagen het als een manier om financiële stabiliteit te bereiken: Suzanne kon haar interesse in kunst volgen, terwijl Bates genoot van wandelingen door het schilderachtige heuvelachtige landschap van Wales.

Naast de £60.000 die ze betaalden voor het bedrijf, namen Bates en Cirone ook de extra kosten op zich om de winkel te renoveren — het elektriciteitsnet en de waterleiding te moderniseren, en een uitbreiding te bouwen die 50% meer vloeroppervlak opleverde. In die extra ruimte konden ze detailhandelsgoederen verkopen naast de postdiensten. Ze investeerden hun volledige spaargeld in het project, in de hoop op een stabiel inkomen en een bloeiend bedrijf voor de komende decennia.

Het leek het recept voor een idyllisch en rustig leven. Bates fungeerde als Subpostmaster, en in 1998 deed hij de boekhouding van de winkel nog met de hand.

Ondertussen begon zich in Londen een storm samen te pakken.

De Britse overheid had het Japanse IT-bedrijf Fujitsu £700 miljoen betaald om een swipecardsysteem te ontwikkelen waarmee gepensioneerden en uitkeringsgerechtigden betalingen rechtstreeks op hun bankrekening konden ontvangen wanneer zij hun lokale postkantoor bezochten. De overheid kende dit uiterst lucratieve contract om twee redenen toe aan Fujitsu: ten eerste stond de toenmalige premier Tony Blair onder zware druk van de Japanse regering, en ten tweede was Fujitsu de goedkoopste bieder van alle concurrerende IT-bedrijven.

En dat was te merken.

Het swipecardproject werd een regelrechte mislukking, en in mei 1999 werd de stekker eruit getrokken. Maar om gezichtsverlies over deze enorme verspilling van belastinggeld te voorkomen, bedachten de overheid — en vooral de Post Office-directie — een omgekeerde oplossing: ze betaalden Fujitsu honderden miljoenen ponden extra om de boekhoudsoftware van het mislukte swipecardsysteem om te bouwen.

Zo werd Horizon geboren — in nogal bedenkelijke omstandigheden.

De Horizon-software was bedoeld om lokale postkantoren in staat te stellen hun transacties te registreren en hun boekhouding elektronisch af te sluiten. Maar vanaf het begin zat het systeem vol fouten. Het kon geen correcte boekhouding bijhouden — het veranderde willekeurig cijfers, verdubbelde transacties en kwam niet tot kloppende totalen. Het was in wezen een miljard pond kostende Excel-spreadsheet die niet werkte — letterlijk erger dan waardeloos.

En door de enorme kosten waren noch de Post Office, noch Fujitsu bereid publiekelijk toe te geven hoe slecht het systeem functioneerde. Als ze dat hadden gedaan, zou het vrijwel zeker hebben geleid tot het ontslag van meerdere hoogbetaalde topmanagers. In plaats daarvan kozen beide organisaties ervoor zichzelf te beschermen en het probleem in de doofpot te stoppen.

In hun publieke verklaringen werd Horizon gepresenteerd als een feilloos systeem dat de Britse postdienst naar de 21e eeuw zou brengen.

Horizon werd in de herfst van 1999 uitgerold naar de eerste postkantoren in het VK.

Horizon werd in de herfst van 1999 uitgerold naar de eerste Post Office-vestigingen in het Verenigd Koninkrijk.

Alan Bates nam Horizon in gebruik in zijn winkel eind 2000.

Binnen enkele weken zag Bates dat Horizon een tekort van £6.000 rapporteerde, maar Bates wist dat dit geld niet zomaar was verdwenen.

Daarom ging hij zijn winkeltransacties nauwgezet na met een fijne kam en ontdekte dat Horizon meerdere transacties dubbel had geregistreerd. Dit verklaarde ongeveer £4.800 van het tekort.

Bates nam contact op met zijn regiomanager om te vragen wat hij moest doen met de resterende £1.200 die zogenaamd verdwenen was, maar hij kreeg geen antwoord.

In de daaropvolgende jaren bracht Bates het onderwerp steeds opnieuw ter sprake bij elke nieuwe regiomanager, maar zij gaven hem nooit een antwoord.

Bates vroeg ook om toegang tot het Horizon-systeem, zodat hij de gegevens aan de andere kant kon inzien. Zijn verzoeken werden genegeerd.

Ondertussen bleven de tekorten in het Horizon-boekhoudsysteem verschijnen, en Bates weigerde zorgvuldig om de berekeningen van Horizon te accepteren. In plaats daarvan liet hij de rekeningen doorschuiven naar de volgende week.

Op deze manier voorkwam hij dat er officieel werd vastgelegd dat zijn winkel een tekort had, waardoor hij volgens zijn Subpostmasters-contract zelf aansprakelijk zou worden voor het tekort.

Bates weigerde ook om documenten te ondertekenen waarin werd verklaard dat de berekeningen van Horizon accuraat waren.

In 2002 werd het oorspronkelijke tekort van £1.200 uiteindelijk door de Post Office afgeschreven als een oninbare schuld.

Maar er waren nog duizenden ponden aan tekorten die Bates niet erkende.

Daarom werd Bates in 2003 opgedragen om te stoppen met het doorschuiven van zijn rekeningen en de berekeningen van Horizon te accepteren.

Na overleg met een advocaat nam Bates schriftelijk contact op met de Post Office en weigerde, met de reden dat hem dwingen om foutieve berekeningen te accepteren, een schending van zijn contract zou zijn.

Als reactie beëindigde de Post Office het Subpostmasters-contract van Bates met een opzegtermijn van drie maanden, zonder een formele reden te geven.

Bates’s laatste werkdag als Subpostmaster was 5 november 2003.

In feite betekende dit dat meer dan £60.000 van Bates’s zakelijke investering verloren ging.

Educational article

The Legal Turning Point in the British Post Office Scandal

The British Post Office scandal, one of the gravest miscarriages of justice in UK history, took a dramatic legal turn through the efforts of Alan Bates and hundreds of sub-postmasters who fought back. This article explores Chapter 3 of the case, from litigation funding to the landmark court judgments.

Background: Mounting Injustice

Between 1999 and 2015, over 900 sub-postmasters were prosecuted due to discrepancies in financial records generated by the faulty Horizon software, developed by Fujitsu. Many lost their livelihoods, faced imprisonment, or fell into debt while the Post Office publicly insisted the system was reliable.

Formation of a Legal Alliance

In 2016, Alan Bates partnered with Therium, a litigation funding firm. With their backing, 555 victims formed a group to take the Post Office to court, initiating the civil case Bates and Others vs. Post Office Limited. This alliance marked a pivotal shift in the struggle for justice.

Legal Battles and Judicial Intervention

The Post Office spent over £100 million of taxpayer funds in an attempt to undermine the case. However, Judge Sir Peter Fraser issued multiple rulings favoring the plaintiffs:

2017: Prevented delay tactics through manipulated scheduling.

2018: Barred the Post Office from invalidating 25% of submitted evidence.

2019 (March): Declared that sub-postmasters weren’t contractually liable for Horizon-related shortfalls.

2019 (June): Forced immediate payment of court-imposed fines to ensure the plaintiffs could continue.

2019 (December): Officially condemned Horizon as deeply flawed, shattering the Post Office’s defense.

The Settlement and Its Shortcomings

Though the court awarded £58 million in damages, only £11 million reached the victims after deductions. On average, each sub-postmaster received around £20,000—a fraction of what many had lost.

Aftermath: Accountability Evaded

CEO Paula Vennells resigned in 2019, having secured over ¤6.7 million in compensation during her tenure. Despite her involvement, she initially retained positions of influence and was even honored with a CBE, later revoked amid public outrage.

Conclusion

Chapter 3 underscores the significance of collective legal action, the abuse of institutional power, and the importance of accountability in public institutions. While the case marked progress, the compensation remains inadequate, and full justice for the victims is still unfolding.

Chapter 2 – Jo Hamilton: A Village Subpostmistress Betrayed

Chapter 2

Jo Hamilton installed a Post Office counter.

In 2003, Jo Hamilton took over the village shop and Post Office in South Warnborough, Hampshire, aiming to serve her community while securing a stable livelihood. However, shortly after installing the Horizon IT system, she began noticing discrepancies in her accounts. Despite her meticulous record-keeping, the system indicated shortfalls that she couldn’t explain.PBS: Public Broadcasting Service+2PBS: Public Broadcasting Service+2Dailymotion+2The Guardian+1The Guardian+1

Believing she might have made errors, Jo attempted to rectify the situation by using her own funds to cover the alleged deficits. She remortgaged her home twice and borrowed money from friends, striving to balance the accounts. The Post Office assured her she was the only one facing such issues, intensifying her feelings of isolation and self-doubt.PBS: Public Broadcasting Service+1Radio Times+1

By 2006, the supposed shortfall had escalated to £36,000. Jo was charged with theft and faced the daunting prospect of imprisonment. To avoid jail, she accepted a plea bargain, pleading guilty to false accounting. This decision left her with a criminal record and a tarnished reputation, despite her innocence.PBS: Public Broadcasting Service+3PBS: Public Broadcasting Service+3Radio Times+3The Irish Sun+4Wikipedia+4The Guardian+4

Years later, it was revealed that the Horizon system was flawed, and Jo, along with many others, had been wrongfully accused. In 2021, her conviction was quashed, acknowledging the miscarriage of justice she had endured. Jo’s story became emblematic of the broader scandal, highlighting the profound personal and financial toll on those affected.Latest news & breaking headlines+3The Guardian+3Radio Times+3

Hoofdstuk 2 – Jo Hamilton: Een dorps-Subpostmaster verraden

In 2003 nam Jo Hamilton de dorpswinkel en het postkantoor over in South Warnborough, Hampshire, met de bedoeling haar gemeenschap te dienen en tegelijkertijd een stabiel inkomen te verwerven. Kort nadat het Horizon-IT-systeem was geïnstalleerd, begon ze discrepanties in haar boekhouding op te merken.

Ondanks haar nauwkeurige administratie gaf het systeem tekorten aan die ze niet kon verklaren. In de veronderstelling dat zijzelf wellicht fouten had gemaakt, probeerde Jo de situatie recht te zetten door de vermeende tekorten uit eigen zak aan te vullen. Ze zette twee keer haar huis opnieuw onder hypotheek en leende geld van vrienden om de rekeningen te laten kloppen. De Post Office verzekerde haar dat zij de enige was met dit soort problemen, wat haar gevoelens van isolatie en zelftwijfel alleen maar versterkte.

In 2006 was het vermeende tekort opgelopen tot £36.000. Jo werd beschuldigd van diefstal en stond voor de verwoestende mogelijkheid van een gevangenisstraf. Om dat te vermijden, accepteerde ze een plea bargain en bekende schuld aan valsheid in geschrifte. Deze beslissing bezorgde haar een strafblad en beschadigde haar reputatie, ondanks haar onschuld.

Pas jaren later werd duidelijk dat het Horizon-systeem fouten bevatte, en Jo, samen met vele anderen, was onterecht beschuldigd. In 2021 werd haar veroordeling vernietigd – een erkenning van het gerechtelijke onrecht dat haar was aangedaan. Jo’s verhaal werd symbool voor het bredere schandaal en benadrukte de diepe persoonlijke en financiële schade die de betrokken Subpostmasters hebben geleden.

Op minuut 13: Hoofdstuk 2

Jo Hamilton installeerde een Post Office-balie.

Hoofdstuk 3 De Tegenaanval

Hoofdstuk 4 Gerechtigheid Bereikt, Gerechtigheid Ontlopen

Chapter 3 Fighting Back

At minute 22

Chapter 3 – A Culture of Denial

As Horizon was rolled out to thousands of branches across the UK, the number of Subpostmasters reporting discrepancies began to rise. Yet the Post Office clung to one central message: “You are the only one.” Subpostmasters who complained were told the system was robust and error-free. Any shortfall was presumed to be the result of carelessness or theft.

Behind the scenes, however, Post Office executives and Fujitsu engineers were well aware of bugs, data losses, and unexplained errors. Internal reports documented multiple faults, and even internal memos acknowledged that bugs in Horizon could create phantom shortfalls. But rather than admit failure, the organization doubled down.

Subpostmasters were routinely suspended, investigated, and in many cases prosecuted. The system was stacked against them. Under the terms of their contract, Subpostmasters were personally liable for any discrepancy, regardless of the cause. And since the Post Office operated as both investigator and prosecutor, defendants stood little chance.

Many Subpostmasters were advised by their own solicitors to plead guilty to avoid harsher sentences. Others were too ashamed to tell family members what was happening. They paid back tens of thousands of pounds, sold homes, lost businesses, and suffered severe mental health consequences—all because of data errors beyond their control.

In 2016, Alan Bates was approached by Therium, a litigation fund where private investors back plaintiffs in civil suits.

They supported the sub-postmasters, and Bates gathered 555 victims to launch a group action.

On March 22, 2017, Bates and Others vs. Post Office Limited was approved.

The Post Office responded by spending £100 million of taxpayer money on legal defense.

They used every legal tactic to stall the case and drain Therium’s resources.

Judge Sir Peter Fraser presided over multiple sub-trials during the lengthy proceedings.

In November 2017, the court stopped the Post Office from using schedule conflicts to delay trial.

In October 2018, another ruling blocked the Post Office from striking down a quarter of the plaintiffs’ evidence.

In March 2019, the court ruled that under their original contracts, sub-postmasters weren’t liable for shortfalls.

The Post Office tried to appeal but was denied twice.

Then they tried to remove Judge Fraser, claiming bias, but were sharply criticized and fined £300,000.

A fifth judgment in June 2019 forced the Post Office to pay that fine immediately to prevent Therium from running out of funds.

In December 2019, the sixth and final ruling concluded Horizon was deeply flawed.

The judge stated its “robustness was questionable” and that the system didn’t warrant the confidence the Post Office claimed.

Facing overwhelming evidence, the Post Office settled and agreed to pay £58 million in damages.

However, £47 million went to legal costs and funders, leaving victims with only about £20,000 each.

Many had lost far more in forced repayments and business closures.

In April 2019, Paula Vennells resigned as CEO but not before accumulating £4.5 million in salary and £2.2 million in bonuses.

She went on to hold high-paying positions at Imperial College Healthcare, Dunelm, and Morrisons, and was honored with a CBE.

Despite the scandal, she remained an ordained priest and even sat on the Church of England’s ethical advisory committee.

Hoofdstuk 3 – Een Cultuur van Ontkenning

Naarmate Horizon in duizenden vestigingen in het Verenigd Koninkrijk werd uitgerold, nam het aantal Subpostmasters die discrepanties meldden toe. Toch bleef de Post Office vasthouden aan één centraal bericht: “Jij bent de enige.” Subpostmasters die klaagden, werd verteld dat het systeem robuust en foutloos was. Elke tekortkoming werd verondersteld het gevolg te zijn van onzorgvuldigheid of diefstal.

Achter de schermen waren de leidinggevenden van de Post Office en Fujitsu-engineers zich echter goed bewust van bugs, gegevensverlies en onverklaarbare fouten. Interne rapporten documenteerden meerdere defecten en zelfs interne memo’s erkenden dat bugs in Horizon spooktekorten konden veroorzaken. Maar in plaats van de mislukking toe te geven, hield de organisatie vast aan haar standpunt.

Subpostmasters werden routinematig geschorst, onderzocht en in veel gevallen vervolgd. Het systeem was tegen hen gekeerd. Volgens de voorwaarden van hun contract waren Subpostmasters persoonlijk aansprakelijk voor elke discrepantie, ongeacht de oorzaak. En aangezien de Post Office zowel de onderzoeker als de aanklager was, hadden de verdachten weinig kans.

Veel Subpostmasters werden door hun eigen advocaten geadviseerd om schuldig te pleiten om een strengere straf te vermijden. Anderen schaamden zich te veel om hun familieleden te vertellen wat er gebeurde. Ze betaalden tienduizenden ponden terug, verkochten huizen, verloren hun bedrijven en leden ernstige mentale schade – alles vanwege gegevensfouten die buiten hun controle lagen.

Dit hoofdstuk in het schandaal onthult niet alleen technische mislukkingen, maar ook institutionele wreedheid. Een vertrouwde Britse instelling koos herhaaldelijk voor het beschermen van haar eigen reputatie boven de waarheid – ongeacht de menselijke kosten.

Op minuut 13: Hoofdstuk 2

Jo Hamilton installeerde een Post Office-balie.

Hoofdstuk 3 De Tegenaanval

Hoofdstuk 4 Gerechtigheid Bereikt, Gerechtigheid Ontlopen

Chapter 4 Justice Attained, Justice Evaded

…Paula Vennells had feathered her nest before departing. Inexplicably, Vennells was made a board member to the British cabinet and became the paid chairwoman of the Imperial College Healthcare Trust.

She also scored a spot on the boards of retail giants Dunelm and Morrisons, collecting an additional £40,000 per year.

All told, during her time as CEO of the Post Office, Paula Vennells squirreled away over £4.5 million in salary and £2.2 million in practically self-nominated bonuses.

Such is life on the gravy train. And Vennells still preached morality from her pulpit every Sunday and remained on the Church of England’s ethical advisory committee.

To top it all off, Paula Vennells was included on the 2019 New Year’s Honours List and made a Commander of the Order of the British Empire for her services to the Post Office by Queen Elizabeth II.

Despite the fact that the 555 sub-postmasters had received very little compensation after a two-year trial, the December 2019 verdict swung the doors wide open for further legal action.

In March 2020, the Criminal Cases Review Commission began the process of quashing convictions. At the time of filming, 101 of the 236 criminal convictions of sub-postmasters have been overturned.

Meanwhile, the British government announced they would hold a public inquiry into the scandal.

On the question of compensating the victims of the scandal, the Post Office declared they did not have the resources to make adequate restitution, and that the financial burden would have to fall on the British government.

This essentially means that the burden falls on the British taxpayer. The government devised three compensation schemes:

First, to more justly compensate the 555 sub-postmasters who had taken part in Bates and Others vs. Post Office Limited.

Second, to compensate a further 2,700 sub-postmasters who suffered financial losses from repaying shortfalls or were prosecuted in civil court.

And third, to compensate those sub-postmasters who were wrongly convicted of crimes.

After a few years of bartering, the British government declared that the 2,700 victims of extortion would be paid a minimum of £75,000 in compensation.

Those victims who were wrongly convicted would get a minimum of £600,000. Evaluation of each case and negotiations over payments are ongoing.

As for the original 555 sub-postmasters from Bates and Others vs. Post Office Limited, the British government has dragged its feet on further compensating them beyond the £20,000 it already won.

But again, negotiations are ongoing. When the government made a compensation offer to Alan Bates, he rejected it outright, saying it was one sixth of what he had asked for and it was, quote, “insulting and derisive.”

Bates also flatly rejected an offer of the Order of the British Empire in the New Year’s Honours List, pointing out that Paula Vennells was still a Commander of the Order.

Speaking of Vennells, in 2021, as public contempt of her grew, she resigned from the Cabinet, Imperial College, Dunelm, Morrisons, and the Church of England Ethical Advisory Group.

But she remains an ordained priest and an extremely wealthy woman.

Vennells has issued several non-apologies over the years for what happened to the sub-postmasters and has repeatedly denied any criminal wrongdoing.

But for the most part, she has simply fallen behind the words “no comment.”

A television miniseries called Mr. Bates vs. The Post Office, dramatizing the events of the scandal, was aired in early January 2024.

For most people in the UK, this was the first time they had heard of the scandal.

Public rage against Paula Vennells reached fever pitch.

On January 8th, an online petition demanding that Vennells return her CBE to the King reached a million signatures.

The following day, Vennells released a public statement saying she would renounce the honour.

On February 23rd, Charles III revoked Vennells’ CBE on the grounds of, quote, “bringing the honours system into disrepute.”

In January 2024, the Metropolitan Police announced it was looking into the possibility of criminal charges against Post Office executives and Fujitsu employees for fraud, perjury, and perverting the course of justice.

At time of filming, no arrests have been made.

Meanwhile, Alan Bates and the Justice for Sub-postmasters Alliance have declared that if the police do not take action, they are looking into going after the perpetrators of the largest miscarriage of justice in British history in civil court.

The fight isn’t over yet.

And it’s very difficult to hold such powerful and well-connected people to account.

It would be a mistake to say that the UK Post Office scandal was an isolated incident.

The abuse of power by high-ranking executives in government departments, government-owned corporations, and even government-subsidized universities is surprisingly common.

All the while they continue to pay themselves very handsomely and feather their nests for the next lucrative job should they have to resign.

Very seldom do these people face any serious legal consequences for their wrongdoing. Maybe a bit of bad press, maybe a financial settlement—mostly borne by the taxpayer—but no jail time.

They are the reason why the word “bureaucracy” was originally a play on words derived from “aristocracy.”

They are an inconspicuous elite—the modern elite—the timid dictators who creep down the hallways of power and parasitically gorge themselves on the public purse.

Furthermore, the UK Post Office scandal highlights a significant flaw in the British justice system, and the judicial branches of the West in general.

If the sub-postmasters, most of whom were financially ruined, had not received the assistance of private investors, they could never have afforded to take the Post Office to trial.

And more often than not, such organizations just hire a crack legal team and outspend the plaintiffs until the case collapses.

And in our case, the Post Office almost got away with it by straining Therium’s resources to the breaking point.

Justice is supposed to be blind. It’s not supposed to discriminate by creed, class, or color.

And yet, frequently, the justice system discriminates by the size of someone’s coffers.

The amount of money we have determines the quality of the representation we get.

Far too often, we don’t get the justice we deserve—we get the justice we can afford.

Hopefully, the victory of the UK sub-postmasters after decades of fighting will prove a turning point in this sad state of affairs.

But it’s likely to be a long time before things begin to change.

Op minuut 13: Hoofdstuk 2

Jo Hamilton installeerde een Post Office-balie.

Hoofdstuk 3 De Tegenaanval

Hoofdstuk 4 Gerechtigheid Bereikt, Gerechtigheid Ontlopen

“Once Upon a Time: The British Post Office Scandal,” is not meant to sound like a fairy tale for children.

It refers to a time before the darkness began — a time when life for Subpostmasters was still normal, decent, and unburdened.

In other words:

“Once upon a time” = there was a time when things were still good, before injustice destroyed lives.

This fits perfectly with the second meaning given in the Cambridge Dictionary:

“used when referring to something that happened in the past, especially when showing that you feel sorry that it no longer happens.”

Exactly as intended:

subtly pointing to the loss of justice, trust, and good life.

It sets the stage for the tragic story that followed.

“The British Post Office scandal is a reminder of the power of truth and the relentless fight for justice — a fight that continues for the victims whose voices were silenced for too long.”

Hyacinth’s Strategically Placed Holiday Brochures Fail to Attract Attention | Keeping Up Appearances